Locking Up Families Is Inhumane—and Unconstitutional

From the fear of asylum-seekers in Western Europe to the panic around “illegals” in the United States, there is a global backlash against immigrants. These sentiments are increasingly accompanied by a crackdown in enforcement. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement placed 352,882 people in detention facilities during fiscal year 2016, a sharp increase from the 193,951 detained in 2015.

U.S. President Donald Trump promises to lock up exponentially more, having made the fight against “illegal immigration” a central plank of his campaign platform. But who are the people incarcerated in these immigration prisons? What are they running from? And do they really need to be locked up for the sake of national security?

While the undocumented population of the U.S. is diverse, those held in immigration detention are often people seeking asylum, or safe haven, from violence. Thousands of the detainees being held by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement are mothers and their young children, most of whom are fleeing harsh conditions in Central America.

One case we have been involved in is that of Rosa and her three children (aged 11, 10, and 2 at the time) who, in July 2014, fled attacks and threats of further violence in their home village in El Salvador, making the dangerous journey through Guatemala and Mexico in search of safety in the United States. [1] [1] All names in this piece (other than the authors’) are pseudonyms to protect people’s privacy. Along their journey, they risked becoming victims of opportunistic crime, including sexual assault as well as corruption and abuse by police. Against all odds, they made it across the U.S.-Mexico border.

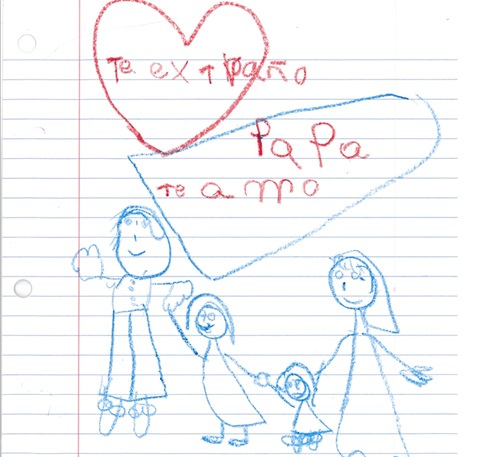

But Rosa’s hopes of securing safety for her family were dashed when they were apprehended by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. They spent several days in what has been called the hieleras (Spanish for walk-in freezers), extremely cold cells at the Border Patrol facilities where undocumented migrants are held. Afterward, they were moved to a long-term facility. Rosa used her one phone call to contact her husband Toño, who was already living in the U.S., to tell him that she and the children were alive. While he was relieved to hear from her after weeks of uncertainty, he was frantic knowing that his wife and children were locked up and that Rosa wasn’t able to tell him where she was being held.

So Toño called Lynnette Arnold (one of the co-authors of this piece and an anthropologist), who had become a close friend of their family during the four years Arnold spent living and working in El Salvador as a volunteer. He hoped she could use her citizenship privileges and knowledge of English to help locate this prison.

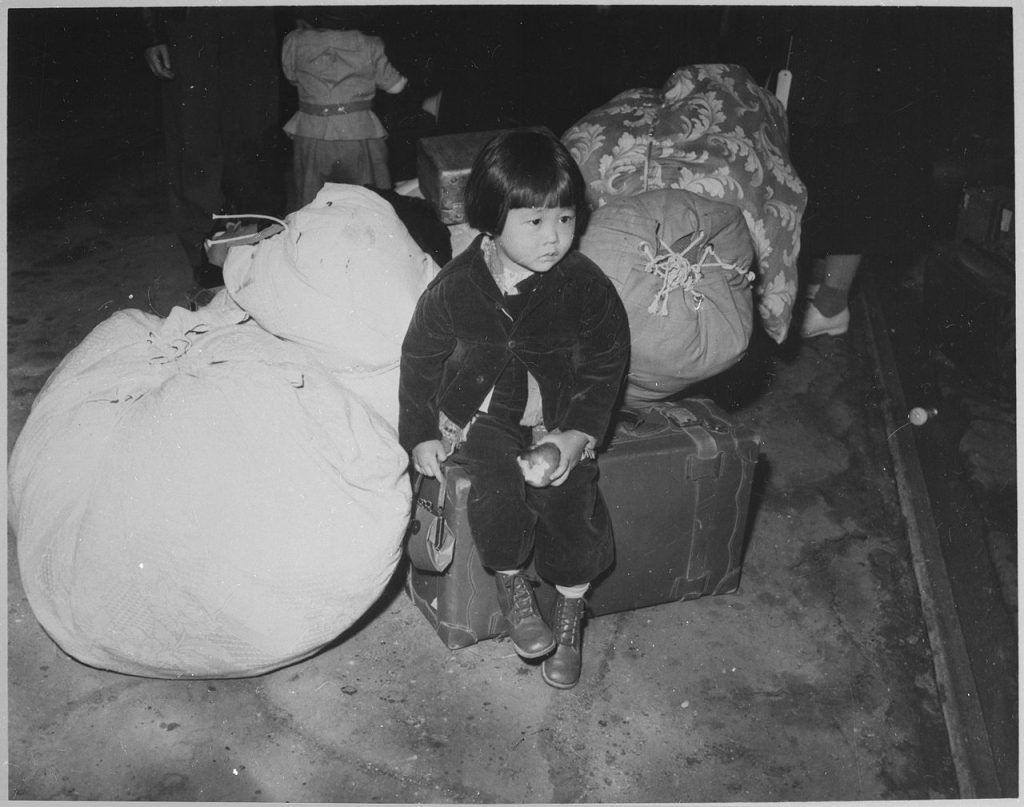

The detention of families seeking asylum has become commonplace in the United States since 2014. While families who were going through the legal process of seeking asylum used to be released to live in society, today they are more likely to be locked up. Families are being imprisoned on a mass scale, the largest instance of family detention by the U.S. government since the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Privately owned, for-profit facilities now hold these mothers and children, sometimes for months at a time, in prison-like conditions.

While former President Barack Obama’s administration is largely responsible for establishing the family detention system, the current administration aims to expand it radically by ramping up the number of unauthorized migrants who are detained and changing the categories of people who are prioritized for deportation. Trump has signed an executive order extending the use of expedited removal, a directive that many argue does not adequately allow for asylum-seekers’ rights to due process. The Department of Homeland Security is even considering a policy that would separate children from their mothers, leaving the women locked up while the children are sent into care elsewhere. This irrational and inhumane practice would directly target families like Rosa’s. In an effort to maintain national security, such policies create personal insecurity for the families affected by them.

In the early days of his presidential campaign, Trump famously made denigrating remarks about Mexican immigrants. While his anti-immigrant rhetoric has not subsided, his target has shifted in the wake of the election. During an interview with Time magazine in late 2016, he gestured to the headlines of a tabloid newspaper and said, “They come from Central America. They’re tougher than any people you’ve ever met. They’re killing and raping everybody out there. They’re illegal. And they are finished.”

President Trump’s recent actions to keep refugees and asylum-seekers from entering the country, his demand for a border wall, and his framing of Central Americans as violent invaders are all part of a widespread revival of xenophobia and white nationalism in the U.S. and Western Europe. This political turn was made possible by the cultural construction, over many years, of alarmist narratives about the contemporary world. In these narratives, which circulate through political rhetoric and various media outlets, the face of global disorder is cast as consisting of black and brown “terrorists” and “drug dealers,” falsely linking such threats to ethnicity and lumping refugees into the same category as transnational criminals.

Central Americans crossing the U.S.-Mexico border are displaced people who migrate to escape violence, lack of viable livelihoods, and environmental crises. They are part of a world on the move, seeking safety and a better life for their children. Refugees and asylum-seekers are fleeing insecurity, and they do not generally pose a threat to the receiving countries. In fact, numerous studies have shown that foreign-born individuals are less likely to commit crimes than native-born citizens.

But you would never know it to hear the alarmist narratives gaining traction in the U.S. The anti-immigrant rhetoric of the new administration, as well as that of resurgent right-wing movements in Europe, actively distorts the character and intent of people fleeing their homes. Migrants are depicted as a national security threat, which allows for the rationalization of punitive and militarized responses to them. Immigration policy and enforcement is one of the primary domains in which the revival of white nationalism is enacted. As increasing numbers of immigrants and asylum-seekers have been locked up over the past few decades, their very incarceration—and the hateful political rhetoric that accompanies it—feeds the misperception that they pose a security threat. These fear-inducing discourses justify the misuse of scarce government resources to persecute undocumented migrants and asylum-seekers, and encourage public consent for the inhumane and unconstitutional treatment of these individuals within the detention and deportation system.

After a frantic two-day search, Arnold managed to locate Rosa and her children at a privately owned, for-profit family detention facility in Texas that had just opened that weekend. All of the detainees—most of whom had traveled to the U.S. from Central America—were mothers and children. Once the family had been located, the next step was for Rosa to apply for asylum, a process involving extensive vetting, complicated paperwork, and multiple interviews with immigration officials. From behind bars, Rosa fought and won her case for asylum—proving that she had a “well-founded fear” of persecution and could not safely return to her homeland. They were released after 10 months of incarceration.

In early June of 2015, she and her children were finally reunited with Toño. During their time in detention, her youngest child turned 3 years old. By release, he had spent one-third of his life behind bars. While they were settling into their new home, he kept asking his mother when they were going back to Room 109, the place where they had been imprisoned.

Arnold visited Rosa and her children twice during their 10-month incarceration and wrote in her fieldnotes about one visit: “Although I had visited maximum security prisons in the past, nothing could prepare me for the sight of children behind bars. Even infants too young to crawl had a detainee identification badge that had to be kept with them at all times. The stress of being locked up was readily apparent: Rosa had dark circles under her eyes and said that she couldn’t sleep at night for worry about her family’s future. The two older children were fearful of the armed guards and kept shushing their younger brother in order to avoid drawing the guards’ attention. Rosa’s 11-year-old daughter clung to me, seeking comfort and reassurance, until one of the guards told her she had to sit on her own chair. All the children had lost weight due to the unfamiliar and highly processed food, and Rosa was forced to spend money on overpriced snacks at the commissary store to feed her hungry children between meals that were scheduled according to institutional convenience rather than the children’s needs.”

Family detention centers are the newest arm of the immigrant detention regime. Their construction was motivated by the immigration surge—dubbed “border crisis”—during the summer of 2014 that caused a media frenzy about rising numbers of unaccompanied child migrants and families from the northern triangle of Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) who were seeking entry into the United States. While numbers of border crossers from this region did increase due to the growing problems of gang violence and police brutality in these countries, the language of “crisis” was twisted to emphasize the alleged threat this “border surge” might pose to U.S. society, leading to the harassment of detained mothers and children.

Many observers framed this situation as a human rights crisis. But the Department of Homeland Security argued that these Central American mothers and children constituted a national security threat, and contended that the flood of migrants needed to be discouraged through an incarceration of the arriving immigrants. The media focused on the increase in detentions, law enforcement, and deportations rather than on the well-founded fear of persecution that is driving people to the U.S., thereby reinforcing the image of migrants as criminals requiring incarceration. (Such alarmist stories were revived in late 2016 as numbers of Central American migrants fleeing violence rose again.)

By the end of 2014, this political and media outcry had resulted in the establishment of two new for-profit family detention centers in the southern Texas towns of Karnes and Dilley, increasing the number of incarcerated mothers and children from fewer than 100 to more than 2,000. (Male household members are separated from their families and sent to facilities for male detainees. At any one time, a total of up to 34,000 immigrants may be held in detention centers.)

Conditions in family detention cause unnecessary trauma and suffering for immigrant mothers and their children. Due to widespread intimidation and abuse by guards, the neglect of serious health problems, and the fact that these centers are not licensed to provide child care, many experts have argued that “locking up mothers and children is unworkable, inhumane, and illegal.” Yet the practice of detaining mothers and children continues and will likely increase under the Trump administration.

Rosa and the other detained women did not accept their incarceration passively. Instead, they organized, confronting enormous obstacles to make their voices heard. One of their first protests happened during a media tour. Several women, including Rosa, gathered in the library, and when they heard a helicopter overhead, they ran out into the courtyard with letters scribbled on sheets of paper to spell out LIBERTAD (freedom).

But this attempt to raise their voices resulted in retaliation; the women were subsequently kept under lock and key whenever there was a media presence. Rather than silencing them, such strategies further emboldened the women. Over Easter in 2015, they engaged in a week-long hunger strike. Hunger strikes have continued to be used by women held in family detention, most recently in August 2016 by 22 mothers who had been detained at the Berks County facility in Pennsylvania for more than 9 months, with children aged 2 to 16 years. The participants wrote: “We are desperate and we have decided that: WE WILL GET OUT ALIVE OR DEAD. If it is necessary to sacrifice our lives so that our children can have freedom: WE WILL DO IT!”

The outrage behind these protests has some legal backing, as the courts have questioned the constitutionality of holding people, particularly children, indefinitely in prison-like conditions without the right to due process or even a bond hearing. A court decision from the 1990s curtailed the government’s ability to hold migrant children and youth under lock and key; an ongoing legal battle aims to have this rule applied to family detention. In 2015, after her release, Rosa spoke at a congressional hearing on family detention and cosigned a letter to President Obama asking him to change the practice of family detention. Spurred by court rulings and protests, Obama’s government did eventually make changes to reduce family detention times to weeks instead of months, although many migrants were forced to wear ankle monitors for continued surveillance after their release.

Under Trump, things are shifting again. His executive order could conceivably increase the detention population to millions of people. He has expanded the use of expedited removal, a hasty process of deportation that was previously applied to migrants who had just crossed the border. Now, any immigrant found anywhere in the country who entered the U.S. without authorization within the last two years may be subject to rapid removal. And he has reversed “catch-and-release,” the practice of allowing asylum-seekers to be free while awaiting their petitions for residency. Once again, families like Rosa’s will need to remain in custody for the months or years that it takes to hear their cases.

When Rosa and her children were finally released in 2015, they had won the right to live and work in the United States. Arnold saw them a few months later as they were settling into their new life. The children were spending time with their father, starting to learn English, and adjusting to the cooler weather.

Rosa’s children seemed happy that day, playing barefoot in a stream by a park. But their family’s position was and is still precarious. While the children are on a path to citizenship, Toño is still an undocumented migrant. Rosa has an in-between status: She has the right to remain in the country, but she does not have permanent residency or an easy path to citizenship. With the political and legal changes under Trump, both could conceivably find themselves targeted for deportation in the years to come.

Family and citizenship are two key values of U.S. culture—so much so that the current system of immigration law is built around supporting family reunification. One of the central criteria for admission as a legal resident is whether a person has family members who are U.S. citizens. The U.S. is also formally committed to protecting and respecting the rights of refugees and asylum-seekers thanks to the 1951 Refugee Convention, a multilateral treaty signed in the wake of World War II. The oppressive and unconstitutional system of family detention is wildly out of step with these regulations and values.

Leaders of the current global order are both obsessed with battling insecurity and good at creating it. Despite hopes that the end of the Cold War would lead to less militarism and global conflict, governments have instead expanded institutions of violence and punishment. Today’s “security” enforcers fight battles that not only fail to provide peace, they foment further displacement. The cost of this emergent global order falls more heavily on vulnerable people, of course, than others. Their suffering increases.

The security-focused stories that circulate in political speeches and policies justify the continued marginalization of such populations and reinforce existing power structures. By stirring up fears among the more privileged, political leaders rationalize these draconian responses, arguing that they are both necessary and sensible. Many people are beginning to reject these narratives, as the past months have seen massive rallies around the world resisting such politics. Listening to excluded voices and little-known stories is a critical part of this resistance. Stories from the margins, like that of Rosa and her family, can counter the xenophobic politics of hate and fear.