Why Are People Who Use Illegal Drugs Demonized?

“It’s our vitamin,” 20-year-old Jarod (a pseudonym) told me, as he and his friends took out a tiny sachet of shabu (methamphetamine). It was late afternoon, and they were about to begin their work as food and beverage vendors at a port in the Philippines. Shabu, they said, boosts their energy as they carry heavy merchandise, gives them confidence to overcome their insecurities and talk to customers, and keeps them awake until the wee hours of the morning, when many interisland ferries arrive.

At first, they were scared to talk about their illicit drug use. But when it became clear I wasn’t a police informant but an anthropologist doing fieldwork, they allowed me to hang out with them. Many of them lack family support, have minimal education, and endure the constant precariousness of poverty. They said they sometimes use shabu to feel good about themselves.

In many ways, they are like young people everywhere—dreaming of better lives, pursuing relationships, expressing themselves through music and art. Once, one of them pointed to his Converse sneakers and asked if I noticed something different. “I like the design!” I said. Laughing, he said he drew it with a ballpoint pen while he was high on shabu.

These are the people Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte wants to kill.

In 2016, Duterte infamously announced at a press conference, “Hitler massacred 3 million Jews. Now, there’s 3 million drug addicts. I’d be happy to slaughter them.” As a result of Duterte’s war on drugs, over 27,000 individuals have been killed in the last three years.

Duterte’s tactics and rhetoric sound exceptionally violent, but the notions that inform them are held by many people around the world. Nine out of 10 Filipinos reportedly back Duterte’s brutal crackdown. In the early 2000s, Thailand launched a similarly murderous—and popular—drug war. In South Africa, one politician said the substance abuse scourge was more detrimental than apartheid. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has blamed drug use, among other factors, for turning young people into gays and lesbians (which he sees as a bad thing).

Even in the U.S., where many states are legalizing or decriminalizing cannabis, attitudes toward people who use psychotropic substances such as heroin, meth, cocaine, and—to a lesser extent—cannabis are generally negative. Only 22 percent of Americans are willing to work with someone who has a drug addiction, according to a 2014 Johns Hopkins study. About 30 percent believe recovery from such addiction is impossible—a view they share with Duterte.

Unroll people’s attitudes about drugs, and you often reveal a hash of racial and socioeconomic stereotypes.

Drugs can certainly be harmful, and there is every reason to be concerned about the consequences of addiction. But the animosity directed at “addicts,” and the impulse to punish them severely, is out of proportion to the threat these individuals pose. Only 11 percent of people who use illicit drugs are “problem drug users”—those who have drug use disorders or dependence—according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. And as Australian researchers Nicole Lee and Jarryd Bartle point out, if harm were the sole measure by which substances were classified as illegal, and condemned as evil and immoral, alcohol would top the list.

Alcohol is responsible for 88,000 deaths annually in the U.S. alone. That’s more than the approximately 70,200 deaths caused by all prescription and illegal drugs combined in 2017. Those death tolls are dwarfed by cigarette smoking, which leads to more than 480,000 deaths annually in the U.S. But moderate drinking is actually celebrated, or at least tolerated, in many societies. And tobacco is much more socially accepted than cocaine or even cannabis.

What, then, can explain the antipathy toward drugs? The answer is a cocktail of history, politics, prejudice, and scapegoating.

Drugs were not always demonized. Psychoactive substances—from alcohol to ayahuasca, cannabis to coca—have been used recreationally, medicinally, and spiritually since time immemorial. They weren’t necessarily seen as dangerous and destructive.

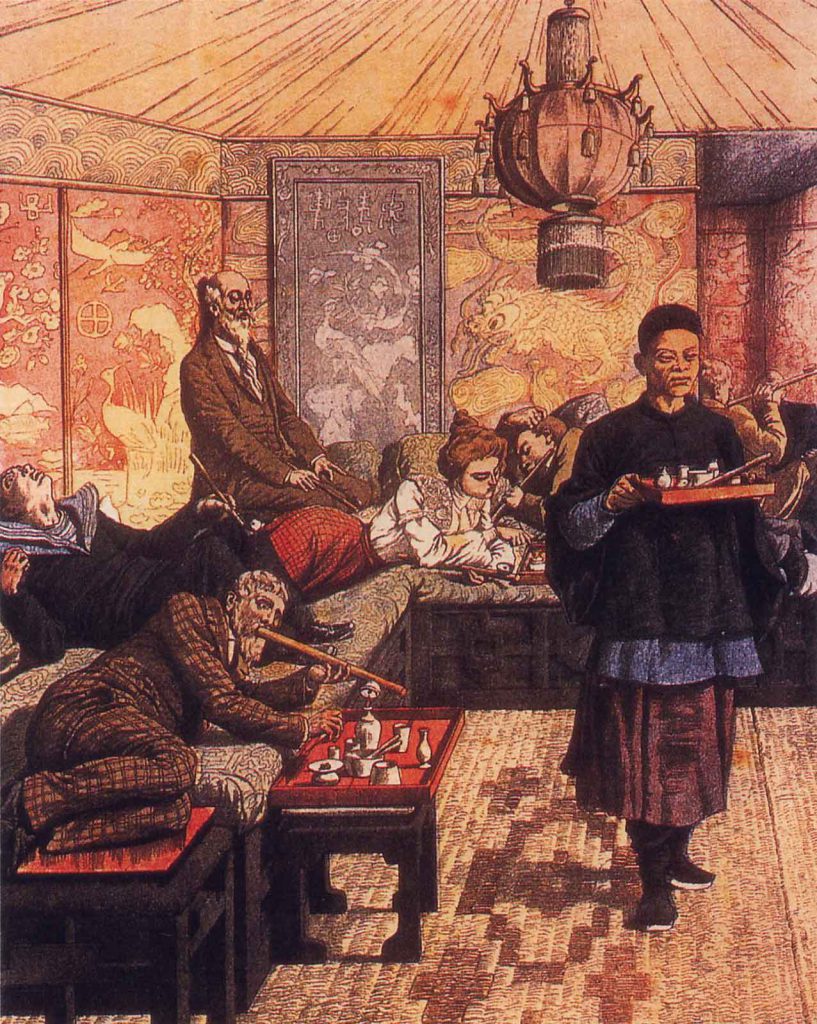

A major turning point was the expansion of the opium trade from the 16th to early 20th centuries. Opium, which had been smoked in some parts of Asia for centuries, was mass-produced by French, Dutch, and British colonial entrepreneurs for a vast Chinese market. Though China banned the narcotic on grounds of morality, British and American traders smuggled it into the country. An illicit and lucrative trade flourished, and addiction ran rampant. When a Chinese emperor confiscated the contraband, the colonialists retaliated, triggering two opium wars.

Opium dens crept across the Western world, as vividly illustrated by Thomas de Quincey in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) and Oscar Wilde, who wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) that these houses of vice were places “where one could buy oblivion, dens of horror where the memory of old sins could be destroyed by the madness of sins that were new.”

While opium was smoked by various demographics, it was primarily linked with the Chinese. Both native Chinese and Chinese immigrants to Europe and North America were accused of immorality and a corrupting influence, in part to justify the wars and the “civilizing” presence of the West in China.

And therein lies a clue to why many hate people who use drugs. Unroll people’s attitudes about drugs, and you often reveal a hash of racial and socioeconomic stereotypes.

In the early 1900s, xenophobia aimed at Mexican immigrants sparked the demonization of marijuana in the U.S. “Marijuana-crazed Mexicans” were blamed for everything from rape to delinquency. In the 1930s, Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner Harry Anslinger launched a drug war on jazz musicians, blaming illicit drug use for crime, the creation of “Satanic music,” and making “darkies think they’re as good as white men.” By contrast, Anslinger tried to help white entertainers overcome drug addiction. Today in the U.S., whites and blacks use illicit drugs at similar rates, but blacks are incarcerated about six times more than whites for drug violations.

Punishment for these crimes is also divided along racial fault lines. From 1986 to 2010, dealing a small amount of crack cocaine (which is often associated with inner-city blacks) would trigger the same mandatory minimum sentence as dealing 100 times as much powder cocaine (which is often linked to high-income whites).

Consciously or unconsciously, drugs can be used as an excuse to justify prejudices against “the other.”

The poor also bear the brunt of drug wars in many parts of the world. “In my country … jail is only for poor small-time dealers, couriers, and individual users; the kingpins typically escape justice,” wrote former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo. In the Philippines, Duterte fuels this double standard, asserting without evidence that rich people’s drugs such as cocaine and heroin are “less harmful” than shabu, which he falsely claims shrinks the brain.

The reasons the poor are targeted more for drug violations than those who are wealthy are complex. Their neighborhoods may be surveilled more often, they cannot afford the caliber of lawyers that wealthy people can hire, or they may be victims of psychological biases on the part of those who make and enforce the law. Legal systems in some countries are known to favor economically privileged and/or white people. In some nations, drug distributors may bribe judges, police, or politicians to maintain their dominance.

All of these dividing lines betray implicit biases against marginalized groups that are deeply entangled with an aversion toward addiction itself. Consciously or unconsciously, drugs can be used as an excuse to justify prejudices against “the other.” And some people exploit these prejudices for their own gain, further entrenching the divisions.

In 1971, then U.S. President Richard Nixon called drug abuse “public enemy number one” and declared a “war on drugs.” One of Nixon’s top advisers, John Ehrlichman, later admitted to Harper’s Magazine:

You want to know what this was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. … We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

Other political leaders have reportedly leveraged illicit drug use as a populist trope to cast suspicion on groups they oppose and to boost support for themselves and their policies. For example, in the U.S., President Donald Trump, who has congratulated Duterte on the “great job” he’s doing fighting drugs, uses the influx of drugs from Mexico as justification for expanding the U.S.-Mexico border wall and imposing new tariffs on Mexico. In Bangladesh, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is waging a bloody drug war that critics say is really a strategy to intimidate political rivals and silence protestors.

In addition, as U.S. sociologists Harry Levine and Craig Reinarman have observed, the right wing has long shone the spotlight on such drug use because it “focuses political attention … away from structural social ills like economic inequality, injustice, and lack of meaningful roles for young people. … It also permits them [conservative politicians] to give the appearance of caring about social ills without committing them to do or spend very much to help people.”

These leaders tend to position drugs and the people who use them as the root cause of societal evils. In reality, drug use is often the result of banes ranging from poverty and disenfranchisement to trauma and generational abuse. But it’s far easier to put the onus on individuals than to tackle massive structural conundrums.

It hasn’t been just politicians like Nixon, Duterte, Bolsonaro, Hasina, and Trump excoriating people associated with drugs. In 1920s Canada, women’s organizations and churches, among others, demanded hard-line action to combat the “drug evil”—which, in an instance of historical parallels, they blamed on opium-smoking Chinese immigrants. In 1970s Philippines, Catholic bishops devoted a pastoral letter to the issue of drug abuse, denouncing producers, planters, and dealers as “the worst saboteurs” who “destroy the youth, the hope of the land.”

But as sociologist Joseph Gusfield points out, these moral crusades waged by privileged groups are, at their core, an exertion of political power. The American temperance movement, Gusfield notes, helped the New England Protestant elite “retain … its social power and leadership” over a growing industrial working class.

Various media outlets also link illegal drug use with crime, economic hardship, and depravity. For example, radio hosts and newspapers in the Philippines routinely blame users, sans evidence, for all kinds of heinous acts. “Only drug addicts are capable of doing such things,” they say of gang rapes and parricide, further cementing the connection between crime and people who use drugs.

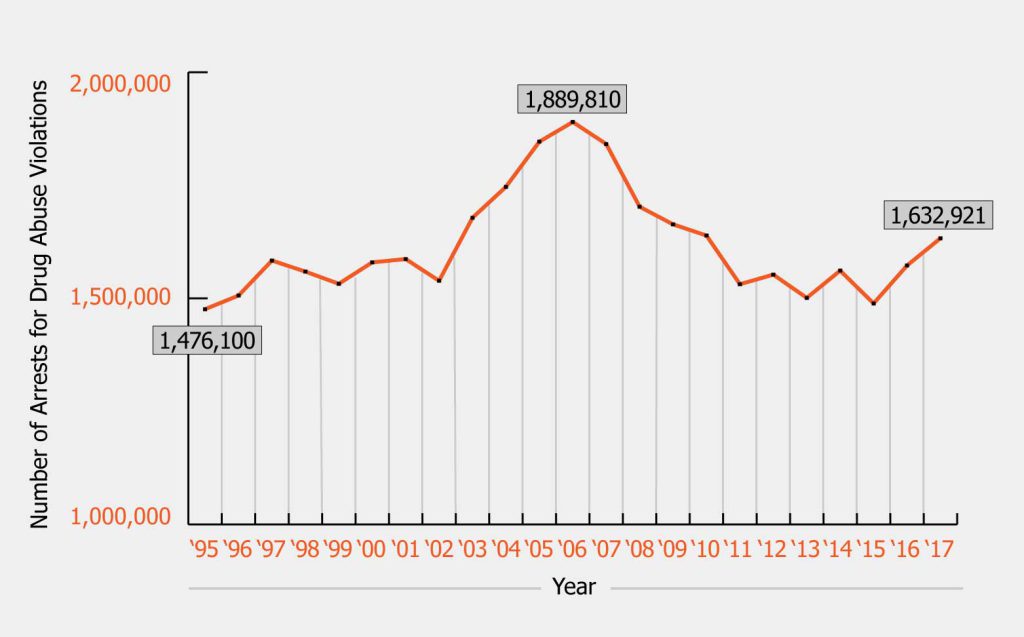

Such stereotypes benefit another sector: law enforcement and the prison-industrial complex. In the U.S., where at any given time nearly 500,000 people are locked up for a drug violation, anti–drug-user rhetoric “establishes the legitimacy of law enforcement as the primary solution to the U.S. drug problem and endorses an unprecedented vigor and reach in applying criminal and civil penalties to those who defy prohibition,” wrote political scientist Diana Gordon.

All of this scapegoating contributes to what medical anthropologists Merrill Singer and J. Bryan Page call “the social value of drug addicts.” It is valuable for certain leaders to claim they are rescuing the public from the bogey men and women supposedly threatening communities. As anthropologist Anita Hardon and co-author Takeo David Hymans note, “The object of drug policy need not be … about drug users at all, but about the political careers of moral entrepreneurs.”

The result of this fear and loathing is stigma and a punitive vicious cycle that harms all of society.

Stigma can prevent people from seeking help, deny them employment, and lead many to go back on drugs. Draconian drug policies, as under Duterte’s rule, often doom individuals and families to further economic deprivation. Some children whose mothers are jailed suffer lifelong trauma. Children in the Philippines have been literally drenched in blood when Duterte’s henchmen shot their parents to death beside them.

The alternative is to rehumanize individuals who use illegal drugs.

People who use and deal illicit drugs certainly can be “agents of destruction in their daily lives,” as U.S. anthropologist Philippe Bourgois wrote. But behind their dependence on drugs often lies what he called a “de facto apartheid ideology” that pushes poor people into situations of such economic insecurity that they feel they need to use drugs to survive.

Many people—from Brazilian truck drivers to Thai students to the Filipino port vendors—use illicit stimulants so they can work and study long hours. In my ethnographic research, I have met young people who want to work in fast-food restaurants and supermarkets, but they fear that the required drug tests will disqualify them and jeopardize their lives. Ironically, many say they would have stopped using drugs if they could get a decent job.

For these individuals, punishment would not only be inappropriate but also detrimental to their ability to support themselves and their families. Drug reform advocates are therefore pressing for more progressive policies and an economic solution to drug use among the poor.

One approach gaining traction is harm reduction, which aims to minimize or prevent the ramifications of drug use rather than punishing individuals. For example, syringe programs have lowered rates of HIV infection. Opioid substitution therapy, which supplies individuals with a prescribed replacement for illicit narcotics, has garnered generally positive results. In China, the Peace No. 1 Rehabilitation Centre in Yuxi City—the first of its kind in the country—offers a broad range of health and social care services. Just over a year after enrolling, more than 50 percent of clients are employed, while less than 10 percent are reincarcerated.

Harm reduction also emphasizes that the repercussions of heavy-handed drug laws are often far more damaging than the substances themselves—hence, the case for decriminalization.

These initiatives deserve to be tested and, if effective, more widely implemented. But they can only become mainstream if the principles behind them are socially accepted. As individuals and societies, then, we need to rethink our prejudices and contradictory attitudes toward people who use illicit drugs.

For instance, world-famous boxer Manny Pacquiao—now also a Philippine senator—has called for the death penalty for high-level drug cases and expressed support for Duterte’s vicious tactics. If I had a chance to talk to the senator, I would tell him about a 17-year-old boy who lived in an impoverished section of Manila and experimented with many drugs while trying to survive in circumstances nearly identical to those of my informants, the vendors in the port. The substances did not destroy his brain. He was not jailed or, like some children and teens today, mercilessly killed. He was given a chance and went on to become one of the richest people in the country.

The boy’s name? Manny Pacquiao.