A Daughter’s Disability and a Father’s Awakening

The nurse gently lifted Michaela onto my partner’s bare chest, a newborn embraced by her mother for the first time. I marveled at the raw beauty of it all. I have a daughter, I thought, and along with my 2-year-old son, the “perfect” family.

Days later, I secretly hoped she would die.

Home from the hospital, I found myself Googling “Down syndrome.” I knew immediately, even though I would languish in denial for a week as we awaited genetic-testing results.

During that week, my entire worldview, a belief system informed by my career in cultural anthropology, began to crumble. Here I was, an expert in a discipline that studies and celebrates the diversity of humankind, struggling to come to terms with a child born different.

Today I am ashamed that I ever felt this way. My love for Michaela is so powerful that I can’t fathom life without her. So why was I initially devastated by her Down syndrome diagnosis?

Michaela’s birth was a typical affair. She arrived early but was a good size and had no health issues, and a nurse invited me to help take her measurements. I picked up Michaela and nestled her close to my body, thinking she felt a bit limp or slightly floppy. I even remarked that she seemed “light,” but the nurse ignored my comment. I placed Michaela on a scale and straightened her legs while they measured her length. I then pressed the bottom of her foot on an ink pad. Her footprint was undeniably adorable, with a cute little gap between her first and second toes. After that I spent hours holding Michaela, peering into her scrunched face, stroking her tiny fingers and hands as she slept. She had puffy cheeks and small ears, almond-shaped eyes, and her round head seemed to disappear into her shoulders. I was falling in love.

I had a faint suspicion in those early hours, but the signs were subtle, and if others noticed, no one said anything—not even the pediatrician. A couple days later, we brought Michaela home.

I spent hours holding Michaela, peering into her scrunched face, stroking her tiny fingers and hands as she slept. I was falling in love.

I don’t remember what prompted me to type the words “Down syndrome,” but I recall with striking clarity the moment I hit “search.” Google spit out its findings, including many callous medical definitions that frame Down syndrome as a “birth defect.” I read about “atypical” characteristics, the underlying chromosomal “disorder,” and inevitable developmental “delays.” I clicked on images and studied seemingly unusual traits—low muscle tone, upward-slanting eyes, small ears, flattened facial profile, a single deep crease across the center of the palm—many portrayed through the crude, somewhat unhuman sketches often used to illustrate diseased conditions on medical websites. I read that the wide space between Michaela’s first and second toes is considered a “sandal gap deformity,” detectable by ultrasound on “abnormal fetuses.” But our ultrasound had shown nothing awry.

It turned out my partner was beginning to harbor her own suspicions. We contacted a nurse, who revealed she had discussed the possibility with a doctor after Michaela’s birth. Since the signs weren’t blatantly obvious, they were waiting to raise the possibility with us. Genetic testing was ordered, but the doctor said she would “bet against” a positive diagnosis. Somehow that comforted me but also filled me with dread. I felt an urge to escape. I went for a walk to nowhere in particular, called my brother, and cried.

I’ve since learned this urge to escape is common among parents who face a Down syndrome diagnosis. The desire to run away expresses the emotional upheaval triggered by news that upends one’s life script—the unconscious narrative of how life is supposed to unfold. Such a diagnosis is extremely disorienting.

It would be a week before we would receive the official results, so I sought refuge in denial. I went to work but avoided my colleagues and tried to lose myself in teaching. I did not bring baby pictures to share, nor stories of Michaela’s birth. At night, with Michaela up in our bedroom, I slept alone on the couch downstairs. I was separating myself, keeping Down syndrome at arm’s length. I am not a religious person, but I prayed for Michaela to be “normal.” I tormented myself with dreadful thoughts: Perhaps she won’t survive these first days, sparing us all.

Such thoughts are not uncommon. Anthropologist Rayna Rapp reports that “many mothers of newborns with Down syndrome recalled praying that their babies would die.” This “fleeting death wish” marks a life crisis, a turning point clouded by profound uncertainty. During that liminal period of not knowing, my partner and I waited at the threshold of a new world, fearful of the change ahead.

How does one tell anxious parents their newborn has Down syndrome? Our doctor was compassionate but also apologetic. I was stunned by the diagnosis, even though it confirmed a truth I already knew, and I immediately felt like I was mourning someone’s death. My partner and I spent the day driving around and talking about how Down syndrome would change our lives. We pondered the future, ours and Michaela’s. Would she be able to ride a bike? Would she learn to drive a car? What about college? Would she get married one day, or ever live on her own?

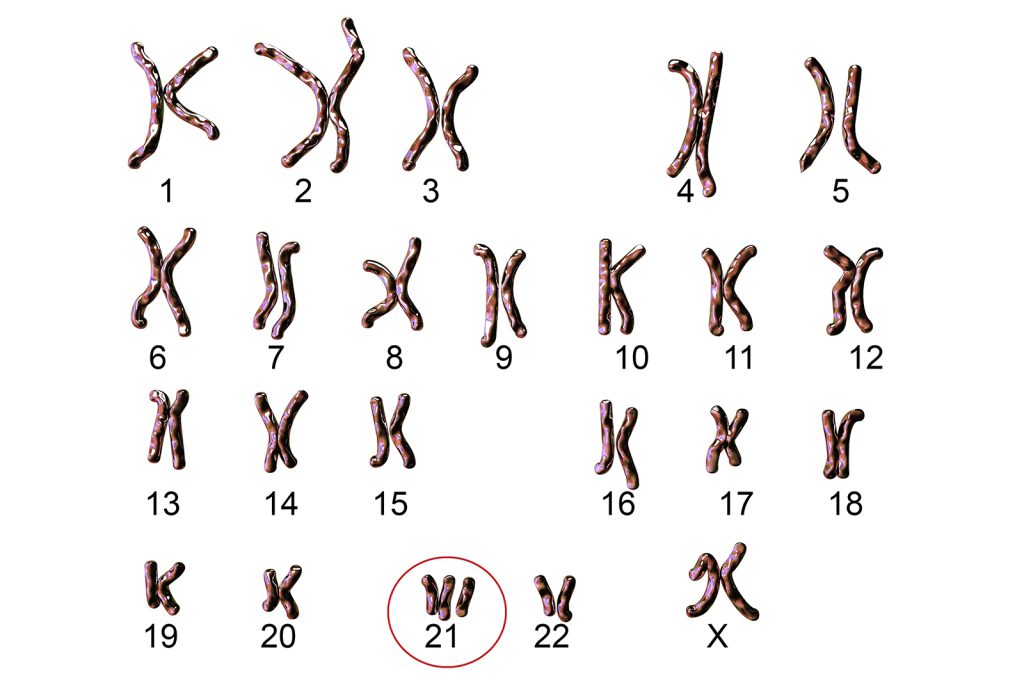

Michaela, now almost 4 years old, is one of the roughly 6,000 children who are born each year in the United States with Down syndrome. She came equipped with an extra copy of the 21st chromosome—three rather than a pair—a chromosomal arrangement known as trisomy 21. The trisomy happens during fertilization; scientists understand how it occurs (a process called nondisjunction), but not why. Trisomy 21 accounts for 95 percent of all Down syndrome occurrences, and less common chromosomal arrangements such as translocation and mosaicism account for the rest. In addition to distinctive physical characteristics, children with Down syndrome are at a higher risk for some health issues, such as congenital heart problems, and often experience challenges with cognitive development. While incidences tend to increase with maternal age, heredity is not a factor in trisomy 21, nor are environmental conditions. Its appearance is random, occurring around the world and throughout human history. It is a natural part of the human condition, part of the diversity of humankind.

When we received the diagnosis, however, I wasn’t pondering the nature of human diversity. I was overtaken by a deeply confusing sense of loss, what I now view as a type of misdirected grief. Abilities such as riding a bike and driving a car—by no means universal or inherent—are widely celebrated as key milestones in the United States. They tend to represent levels of personal autonomy and independence, particularly in the type of suburban setting where I grew up. Likewise, going to college, getting a job, marriage, owning real estate—these have become benchmarks of middle-class success, empty boxes to check off in the pursuit of happiness narrowly defined as becoming wealthy and shoring up class status. This is not a recipe for wellbeing, but rather an ideology of material achievement dictated by our economic system and our cultural emphasis on individualism. My loss was not that of a child, but an idea, an unconscious expectation about what it means to be human and what a supposedly good life entails. I was mourning the loss of an imagined future.

My initial sense of loss was reinforced by well-meaning friends and family. Unlike other momentous occasions in life, there is no cultural script for how to support a loved one whose child is diagnosed with Down syndrome. Some expressed sympathy or said they were “sorry,” echoing the doctor who had delivered the diagnosis. Others commented about how conditions for “the handicapped” have improved in recent years or they inquired about my “special needs” baby. Seemingly kind words sent an unspoken message: Grieve a tragic event and envision a difficult journey.

I found these gestures unsatisfying. What newborn doesn’t have special needs? What were they sorry for anyway? Sorry that my child was not “perfect”? Sorry that we had the “wrong” baby?

Such gestures illuminate the continuing prejudice against people with Down syndrome, despite many improvements in recent decades. A century ago, Down syndrome was commonly referred to as “mongolism,” a social evolutionary classification that defined the condition as a form of racial degeneracy. It was often assumed that children with Down syndrome were incapable of learning, of being fully human. They were socially isolated and frequently institutionalized, often in cruel conditions. Based on beliefs derived from eugenics, many were subjected to forced sterilization in the United States, and they were among the first groups targeted for mass extermination in Nazi Germany.

Perceptions have changed dramatically since the 1960s, when parents and self-advocates fighting against social exclusion fueled the growth of disability rights activism. They challenged the logic of institutionalization, demanded access to health care, pushed for inclusive education, and advocated for support systems to enable increased autonomy and independent living, struggles that resulted in major policy changes, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Today, people with trisomy 21 exhibit a range of abilities and increasingly lead meaningful lives in their communities. While trisomy 21 contributes to diverse developmental outcomes, many people with Down syndrome ride bikes, succeed in school, get married, find jobs, and live independently.

Yet biased attitudes linger, and the diagnostic language of modern medicine continues to draw lines between “normal” and “abnormal” humans. I not only encountered this in my initial frantic Google search, but I have heard medical professionals use the term “simian crease” to describe the single deep crease along the center of the palm of some individuals with Down syndrome. It’s a term that, while falling out of usage in recent years, harks back to the days when Down syndrome was assumed to represent some “primitive,” ape-like stage of human evolution.

In receiving a medical diagnosis, new parents also navigate what Rapp calls the trope of “alienated kinship.” In her research in the 1980s and ’90s, Rapp found that newborns with Down syndrome were often described as lacking family resemblance with their parents, a description that cast the newborn as alien or inherently different. Babies with Down syndrome are often talked about as having more in common with each other than with their families of origin. When we first suspected Michaela might have Down syndrome, a doctor highlighted various characteristics she did and didn’t have, and whether the features resembled me and my partner. After genetic testing confirmed the diagnosis, one doctor assured us that “they’re such happy people.” They. Them. Those people. While infrequent, medical professionals also periodically called Michaela a “Down’s baby,” as if she belongs to some other group aside from her family.

These are labels that set boundaries, that distance and subtly dehumanize. Lurking within this language is the assumption that Down syndrome represents a deficient existence. This is borne out by the high termination rates of fetuses prenatally diagnosed with trisomy 21, which studies suggest range from 60 to 90 percent in the United States and from 89 to 95 percent in the United Kingdom. The desire to screen for trisomy 21 and these resulting termination rates occur in a cultural context where certain forms of human diversity are stigmatized as undesirable or perceived as burdensome.

It’s not surprising I initially experienced Michaela’s diagnosis as tragic. Despite my training as an anthropologist, a discipline that aspires to understand, not judge, human differences, I had inherited a severely flawed cultural toolkit for handling the unexpected news. For weeks after Michaela was born, I thought about her Down syndrome almost daily and saw her through the distorted lens of the diagnosis.

Anthropology eventually helped me to challenge the supposed naturalness of this lens and see it as something strange. What does this diagnostic category tell us about the society that generated it? What really does it mean to be human? And what do I actually value as a father? I want and expect Michaela to strive and achieve, but I now question overly narrow conceptions of success. Our cultural emphasis on individual achievement is dangerously selfish and tethered to a value system that degrades entire groups of people who are stigmatized as existing outside the boundaries of normalcy. But these boundaries are arbitrary, and the very category of normalcy is a fiction.

Michaela teaches me this every day. My experience parenting her has helped me to prioritize values such as compassion and unconditional love. This has made me a better father and a better anthropologist. I have come to see disability as a natural form of human variation, part of the shared human experience. I also believe we can do better to build a society that not only accommodates this variation but also ensures that all people have the opportunity to flourish and belong. My daughter’s Down syndrome has not changed my life in the ways I once feared. It has only clarified what’s truly important.