What Does It Mean to Decolonize Heritage?

Most tourists visit the district of Nyanza in Southern Rwanda because of its storied past as the seat of the Rwandan monarchy, which ended shortly before the nation’s independence from Belgian colonial rule in 1962.

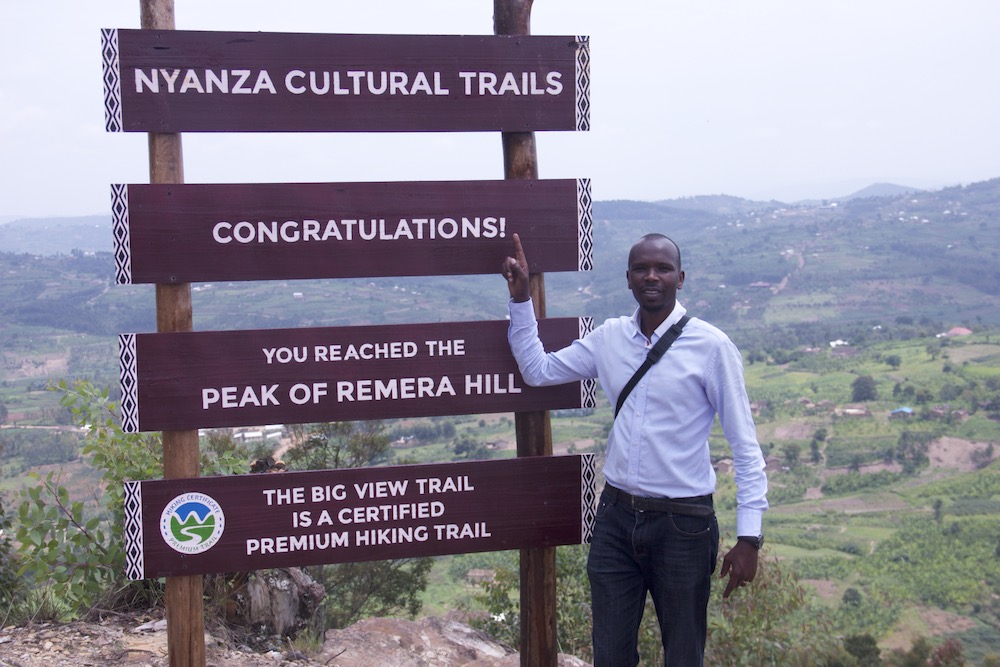

In Nyanza city, the district capital, visitors can marvel at the reconstructed palace of Rwanda’s last umwami (king) or observe the long-horned Inyambo cattle, a heritage breed descended from royal stock. Hikers can also follow signs to the Big View Trail, an 8-kilometer route from the city that winds across rolling hills and in between small farms full of banana trees to the top of a peak called Remera Hill, a spot with stunning, 360-degree views where people sometimes come to pray at a cross known as Calvary. Visitors can also choose the 10-kilometer Royal Trail, which connects cultural heritage sites related to Nyanza’s royal history.

Or at least that’s the idea. Nyanza’s trails were launched in 2019, complete with signage put up by the Rwandan government in collaboration with the German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). But in 2020, something unexpected occurred: Some local residents ripped down the signs and left them lying on the ground. They feared that the trails, which they associated with tourism and infrastructure development, were just a first step toward the government taking their land for other projects that wouldn’t benefit them, like building roads through their fields.

On the surface, the dispute was about signage. But it was also about something bigger: Who gets to make decisions about the uses of a community’s heritage—and who benefits?

As the Rwandan government seeks ways to develop the country’s economy in the wake of the devastating Genocide Against the Tutsi in 1994, it has landed on tourism as a major driver. This includes tourism centered on Rwanda’s famed mountain gorillas and, increasingly, sites linked to the country’s rich cultural heritage.

Nyanza is an igicumbi cy’umuco n’amateka (cultural and historical hub), where most residents are small-scale farmers and, according to the government, approximately half live in poverty. Heritage-based tourism is meant to benefit all Rwandans, including bringing economic growth to places like Nyanza. But as the signage incident shows, these good intentions may not be enough to overcome fractures between some local residents and the government.

This situation is not unique to Rwanda. In recent years, debates about heritage management have boiled over into protests around the world. Many of these protests have been linked with calls to “decolonize” historical monuments: In South Africa, for example, the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement started with protests over a statue of British colonizer Cecil Rhodes on the University of Cape Town campus. In Belgium, demonstrators have campaigned to bring down statues of King Leopold II, whose brutal reign in what is now Democratic Republic of Congo killed millions.

But these tensions over colonial legacies are not limited to the explicit memorialization of individual colonialists in the public sphere. Colonialism continues to operate behind the scenes of many contemporary heritage management projects, shaping who can make decisions and who benefits from them.

In Rwanda and beyond, heritage management professionals, archaeologists, and other scholars are now looking to new models of collaborative, community-led management of resources like Nyanza’s cultural landscapes and historical sites. These approaches may help to redress these historical injustices—but decolonization is not a one-size-fits-all project.

Our recent study, led by an anthropologist (Bolin) and heritage management practitioner (Nkusi), explores how decolonizing heritage management might work in Nyanza and where it might intersect with other decolonizing efforts elsewhere.

African scholars have demonstrated how colonial systems of management across Africa took away people’s right to manage and control their own heritage—often making communities feel disconnected from the traditions and material and historical remains of their pasts. This alienating system of top-down management in many cases continued beyond independence, ensuring that colonialism’s invisible legacy persisted.

This same pattern of top-down, exclusionary heritage management prevailed in Rwanda until recently, with a new heritage law that is expected to put more decision-making power into the hands of communities to identify and preserve heritage resources. Not only are such changes ethically necessary, they also have practical benefits: By ensuring that heritage remains meaningful and valuable to local residents, they may avert conflicts like those over Nyanza’s trails.

As a scholar and as a practitioner of Rwandan heritage management, we wanted to find out more about how communities in Rwanda were relating to heritage resources in their district. What were the impacts of current management systems, and would it be possible to make heritage management more responsive to communities?

We undertook a field research project in October 2020 to investigate these questions, speaking to 48 stakeholders in Nyanza District. We talked to heritage professionals and consultants, government authorities and business owners, and (the largest and most important group) local leaders.

Our respondents consistently acknowledged that Rwanda’s top-down management system has alienated local communities. They said there was little connection between heritage resources and local people’s lives. At the same time, most of our respondents thought that heritage was and could be significant for the future of Nyanza’s residents—but that would require a shift in how it was handled.

The most interesting idea for changing heritage management—and one that sheds light on how heritage might be decolonized in Rwanda—came from local leaders who represented groups of 14–20 households, the lowest level of Rwandan governance. We conducted interviews with these leaders at their agricultural fields and at local heritage sites such as Icyuzi cya Nyamagana, a lake that serves as one of the stops along the Nyanza trails. The lake was constructed as a fish-farming site at the direction of King Mutara III Rudahigwa after the Ruzagayura famine from 1943–1944. Still, despite its historical significance and integration into the tourism circuit, local people told us they had received little economic benefit from its presence.

Local leaders told us: “We need to be trusted with a sense of responsibility in the management of our heritage.”

Standing at the lake’s shore, local leaders told us, “We cannot own what we do not understand. We cannot own [anything] when we are not part of the entire process of management and planning.”

These leaders shared that the way to change heritage management in Nyanza was to focus on creating an “ownership mindset” through active collaboration with local communities to manage sites. This would repair the rupture between communities and heritage management institutions, enabling people to benefit from these resources socially and economically.

But this approach would require a shift: Local communities would have to be brought into the decision-making process at every step. They wanted their needs considered when heritage was developed for tourism, and they wanted the profits to go toward local projects they chose.

“All in all,” the leaders told us, “we need to be trusted with a sense of responsibility in the management of our heritage.”

Scholars have made similar arguments about the need to shift toward bottom-up, grassroots forms of heritage management. But Nyanza’s local leaders tend to articulate these ideas in ways that echo discussions in Rwanda about decolonization. They rely especially on two concepts—agaciro and kwigira in the Kinyarwanda language—that convey dignity, self-reliance, and self-worth in locating Rwandan solutions to Rwandan problems.

Agaciro and kwigira manifest in a number of ways, but both terms act as guiding philosophies for the current Rwandan government as it seeks to establish a peaceful, secure, and increasingly developed post-conflict nation. The pursuit of self-reliance can be found in Article 11 of the Rwandan constitution, which exhorts the country to locate solutions to current problems in the Rwandan past—in other words, in its heritage. These ideas circulate in the field of international relations as well, where Rwanda agitates for independence from outside influence and intervention, especially foreign aid.

Likewise, when local leaders in Nyanza use these terms to call for communities to participate in and benefit from heritage, they are advocating for a form of decolonization: taking power from centralized, top-down systems inherited from colonialism and returning it to local communities.

So, what does it mean to decolonize heritage?

It’s not just about removing statues of colonial figures, as so many countries have done over the last year or two. In Rwanda, the answer lies in changing who heritage management is responsible to so communities benefit, and in connecting heritage-based tourism to larger national projects of building dignity and self-reliance.

These lessons from Nyanza could help the rest of us think about contexts other than Rwanda too. What colonial legacies persist invisibly in the management of heritage? How can those frameworks be decolonized to make heritage a living, grassroots project that has meaning to all sorts of people?

Nyanza’s local leaders told us that this kind of bottom-up engagement with and ownership of heritage would have real material consequences. But unless local residents were involved from start to finish in heritage development, they said, “heritage resources will always be neglected by us.”

Until then, local people will likely continue to see heritage management efforts like the Nyanza trails as a threat to their sovereignty, not an opportunity. That’s what’s at stake when hikers follow the signs to that beautiful view at the top of Remera Hill.