Crystal Worl’s Countermural Tells a Different History of Alaska

Her dark gray eyes scan the horizon. An iridescent golden sun and stars encircle her head, flanked on one side by a cobalt sockeye salmon and the other by a raven’s wings. Her name is Elizabeth Peratrovich, and she is currently gazing across the Gastineau Channel from her new outlook on a mural in downtown Juneau, Alaska.

Tlingit, Athabascan, and Yupik artist Crystal Kaakeeyáa Worl painted Peratrovich into her new home during the late summer of 2021. Worl employed a team of apprentices to install the three-story portrait of this Indigenous civil rights icon onto the public library’s exterior wall.

Peratrovich is not the only muraled resident on Juneau’s docks. Sitting adjacent to her portrait is another, smaller mural. Installed in 1986, this piece depicts Ancon, a 19th-century steamship, with a few dozen passengers whose pale faces contrast starkly with their heavy black attire. The stoic subjects of this painting are the settler colonialists who arrived in Juneau a century earlier, many of whom carry family names still recognizable today.

The contrast between these murals is more than just aesthetic: They communicate two different perspectives on Juneau’s history.

As tourists today disembark the cruise ships that dock near the murals, they simultaneously witness a story of settlement and a story of resistance, of White families who colonized Áak’w Kwáan territory—an area that includes much of present-day Juneau—following the establishment of a local gold mining industry in the 1880s, and of the Tlingit activist who fought to protect Alaska Native rights just decades later in the 1940s.

In painting Peratrovich adjacent to the steamship mural, Worl has effectively installed a countermural: a commemorative public image that depicts an alternative to the dominant visual representation of the region’s history.

Her work fits within a growing body of public art in the U.S. that seeks to push back against the overwhelming presence of White or colonialist figures that often visually overtake the landscape. As Crystal Worl affirms, “This is time for me to stand up and make artwork that will be seen and that will tell people—tell our nation—that I’m an Indigenous woman, I’m here, I exist, and I’m here to uplift this icon figure that represents who I am and a community where I come from.”

Countermurals allude to the more widespread concept of countermonuments, a term introduced by historian James E. Young in a 1992 article about Holocaust memorials. He presents countermonuments as products of macabre contradiction, self-conscious methods to both remember and challenge the very events that led to their constructions.

Young highlights the work of contemporary German artists who installed structures that critiqued and undermined the state-sanctioned power typically imbued in monuments. Such pieces, he says, “contemptuously reject the traditional forms and reasons for public memorial art,” paving new purposes and modes of expression for commemorating that which is noticeably absent.

Seen as a relative of countermonuments, countermurals stand apart for their ephemerality. While a mural’s wall may remain standing alongside a stone or metal statue over time, the paint will eventually fade and chip without regular maintenance. The steamship mural has already begun to decay in Juneau’s constant rain and infamous Taku Winds.

Aware of such climatic threats, Crystal Worl borrowed a technique refined over 30 years by muralist Ben Volta in Philadelphia, whose pieces have withstood the test of time. Worl printed her design on mural cloth, a non-woven fabric with two coats of weatherproof and UV-protected primer, before adhering it to the façade and painting on top of it. It’s the first mural of its kind in Juneau.

Nevertheless, Worl acknowledges the potential for Peratrovich to disappear in the future. She envisions a Juneau “so packed with murals that they’ll have to paint over [the steamship] mural; they’ll have to paint over my mural.”

That Worl’s countermural came about in the past couple of years is not coincidental. In other parts of the U.S., countermurals have emerged in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests following the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. In addition to commemorating the victims and honoring the movement, these artistic pieces responded to an absence of Black artists in public spaces and criticized racialized police brutality. Amateur and professional artists alike transformed blank walls and city streets into markers of Black people’s presence and resistance to reclaim space and power.

These countermurals—and the broader fight for racial justice—contributed to the development of Worl’s piece. A couple years ago, Worl’s friend Pat Race, the owner of Alaska Robotics, a gallery in downtown Juneau, approached her about a mural showcasing local Indigenous art. Their initial plan was to install the mural a few blocks away from the docks but, due to structural concerns with the wall, they had to change course.

Crystal Worl quickly recognized the merits of the new location. For one thing, it overlooked the channel—an important connection to the sea that held cultural value. “We prefer our Tlingit totem poles to be facing the water,” Worl explained. “There’s significant importance to the water and subsistence with life in the water.”

In addition, placing her mural next to the steamship allowed Worl to make a strong public statement. “Juneau used to be this place where visitors would dock and the first thing they would see welcoming them was this very White family mural,” she said. Walking through the streets would yield information about Juneau’s history as a mining town but would inevitably relegate Alaska Native representation and art to the gift shops, taking the form of a “totem pole shot glass” or a “thing made in China,” as she put it.

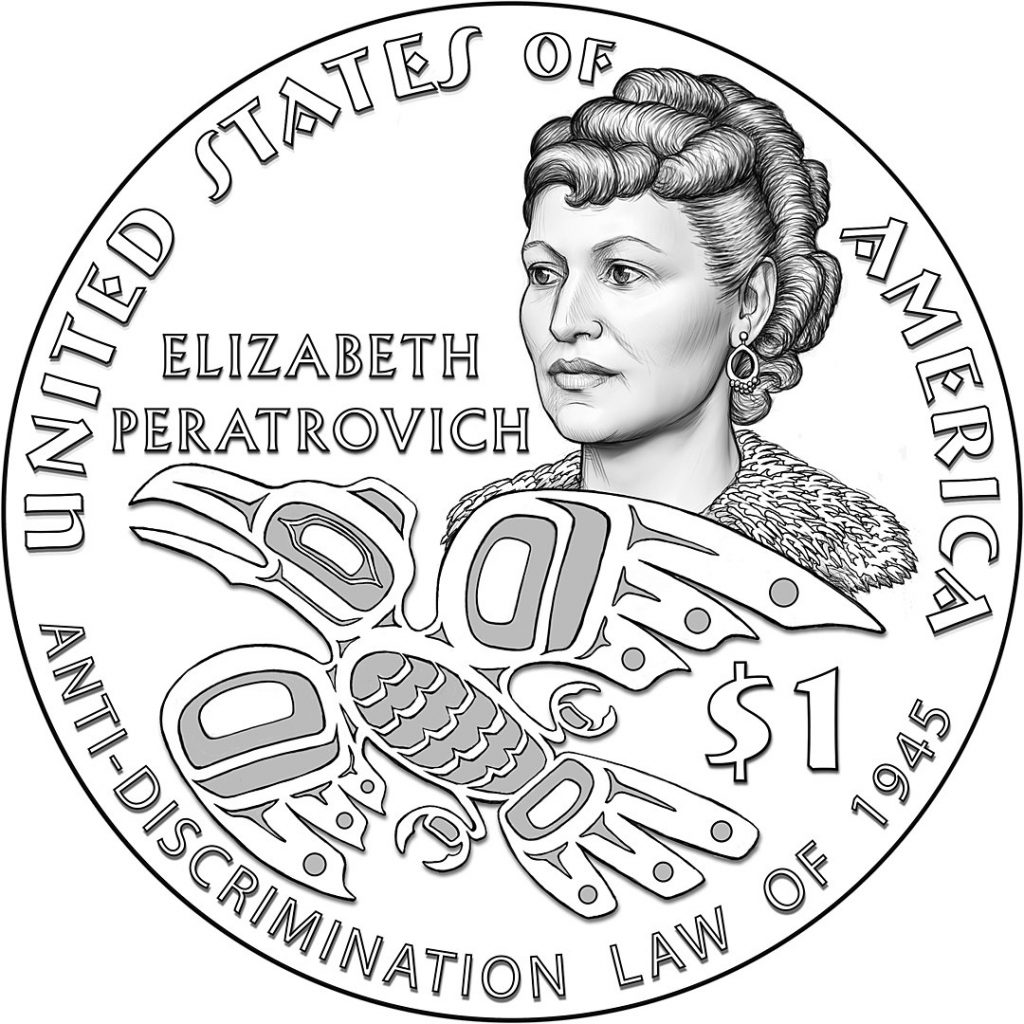

For Worl, positioning a prominent, local Tlingit activist at the marine entrance to the city could help rectify the visual absence of Indigenous representation in town. Peratrovich is known for her advocacy surrounding the passing of the state’s Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945—the first of its kind in Alaska—and her tenure as president of the Alaska Native Sisterhood. In recent years, her image has surfaced in more popular arenas, appearing on the face of a U.S. dollar coin, in a Google doodle by Tlingit artist Michaela Goade, and even in a recent episode of the PBS animated children’s show Molly of Denali.

“This is time for me to stand up and make artwork … that will tell people—tell our nation—that I’m an Indigenous woman, I’m here, I exist,” says Crystal Worl.

Worl also has a personal connection to Peratrovich: They are both members of the Lukaax̱.ádi Sockeye clan, part of the Raven moiety—one of two descendant groups within Tlingit lineage. This affiliation influenced Worl to include both Raven and Sockeye imagery in the mural. Worl often honors Raven, a trickster figure well-known in traditional Tlingit stories, in her contemporary designs.

As she worked on the project, Worl spoke with Peratrovich’s descendants over the phone. She also talked with individuals involved in the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaskan Native Sisterhood who reached out. These conversations helped Worl better understand Peratrovich’s legacy and also connected her, she says, “with people I already knew, and with people I haven’t met yet in the community.”

Building these community ties made the process all the more meaningful for Worl.

Crystal Worl’s countermural can be seen as a step in the right direction for Juneau’s art scene, which has not always prioritized Alaska Native representation.

In 2017, Juneau unveiled a statue of William H. Seward outside the state Capitol as part of a 150th anniversary celebration of Alaska’s purchase from Russia. Seward was the U.S. Secretary of State who facilitated that land purchase without the consent of sovereign Native peoples.

Art historian Emily Moore details how residents of the village of Saxman in southeastern Alaska raised a countermonument that same year to criticize Seward for his unpaid debt to the community. Created by local Tlingit artist Jackson Polys (a.k.a. Stephen Paul Jackson and Stron Softi), the “Seward Shame Pole” ridicules Seward for not reciprocating the outpouring of gifts he received from Chief Ebbits during a visit to the Tongass Village in 1869. Polys’ pole replaces two earlier versions of the shame pole erected first in the 1880s and later in 1941. It stands as a reminder of not only Seward’s debts, but also of Alaska Native peoples’ resistance to settler colonialism.

During a public talk about the pole in 2017, Worl’s grandmother Rosita Worl, a Tlingit anthropologist who leads Sealaska Heritage Institute, said of the Seward monument: “I don’t object to that statue that we have up on the Capitol. What I object to is that the story of Alaska Natives is not there adjacent to that [statue].”

Crystal Worl’s countermural answers that call by placing Peratrovich directly next to the steamship. The juxtaposition invites passersby to consider the different versions of Alaskan history that both paintings represent together.

Worl hopes her mural is “opening a doorway”—paving the way for future artists to “step up and do the work and help Juneau become more colorful.”

Hints of a changing Alaskan public art scene are already in motion. Sealaska Heritage Institute has secured funding to install a totem pole trail along Juneau’s downtown waterfront, with plans to celebrate the inaugural 360-degree pole by Haida carver TJ Young on June 8. This summer in Anchorage, Worl is partnering with the Alaska Mural Project, the Anchorage Museum, and local artist James Temte to install a countermural she designed that responds to a preexisting mural of the city’s history, one that gives scant attention to the Dena’ina and other Native peoples in the area.

And the Peratrovich mural is just the start of a larger project on the Tlingit activist. Race, Worl’s colleague who was instrumental in creating and executing the mural, is now producing a documentary about Worl and the newly named Peratrovich Plaza. Worl also plans to publish an educational page on her website about Peratrovich’s significance to Juneau and Alaska Native rights.

“I used to look up at that wall and feel frustrated,” Worl says. “Now I can look up at the wall and walk around the corner and see, ‘OK, our history is here, too, and we’re here, too.’ And I’m proud to say that.”