Can We “See” Climate Change?

While standing on the Senate floor in Washington, D.C., in February 2015, Republican Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma expressed his deep skepticism about climate change. “We keep hearing that 2014 has been the warmest year on record,” he said, taking a snowball out of a clear plastic bag. “I ask the chair, you know what this is? It’s a snowball,” he said, “from outside here. So it’s very, very cold out. Very unseasonal.” With that, he tossed the snowball toward the president of the Senate, saying, “Catch this.”

In response to Inhofe’s performance, Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island gave a rebuttal. Citing organizations “who are very clear that climate change is real,” Whitehouse invited listeners to trust the conclusions of NASA, the U.S. Navy, faith groups, and major corporations like Pepsi and Ford. “You can believe NASA,” he said, “and you can believe what their satellites measure on the planet, or you can believe the senator with the snowball.”

The contrast between Whitehouse and Inhofe points to the critical role that experience, visibility, and trust play in debates about climate change. Even though climate science predicts that warmer lakes and seas will lead to more intense snowstorms in some places, skeptics see things differently. Events such as freezing weather and winter storms are taken as evidence that climate change is not happening. Inhofe’s act may have been theatrical, but it reinforced a common question in the public eye: If it’s freezing outside, how could the climate be getting warmer?

While the overwhelming scientific consensus is that the climate is changing and the globe is warming, climate change is a complex process that can be difficult to fully grasp. For this reason, it is important to pay attention to the arguments of climate skeptics—not just to refute them but to understand why their claims can be convincing. Rather than abstractions, Inhofe offered a tangible example: A snowball on a cold day is a reminder that the visible world around us matters. Yet the world around us should not only be a vehicle for encouraging doubt—it also offers a wealth of concrete, visible evidence that the climate is changing.

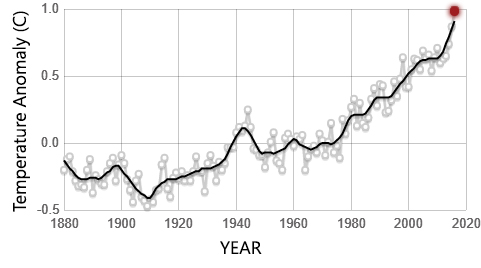

As part of an effort to counter skeptics, climate scientists focus people’s attention on broader climatic trends, not individual weather events. NASA explained it this way in 2005: Weather is a manifestation of atmospheric conditions “over a short period of time,” whereas climate “is how the atmosphere ‘behaves’ over relatively long periods of time.” Because global warming is understood as the increase in average temperatures over time, weather events become part of that average—so a snowball doesn’t represent a statistical average any more than a warm day in the fall does.

But statistical abstractions have contributed to the idea that climate change cannot be seen, which anthropologist Peter Rudiak-Gould calls “invisibilism.” If climate change is believed to be invisible, he writes in the 2013 journal article “‘We Have Seen It With Our Own Eyes’: Why We Disagree About Climate Change Visibility,” then it “becomes the province of specialists, and the role of the public is limited to lending those experts the support and trust they deserve.” The consequence is that people’s everyday experiences are minimized. In his article, Rudiak-Gould asks, “How can people find personal meaning in something they do not see, something they cannot see?”

For someone inclined to be skeptical, the experience of an unusually cold winter—or seeing a senator toss a snowball—can strengthen doubts. What is more real, going outside and sinking your hands into a snowdrift or viewing a graph showing increasing average global temperatures? For those who are not inclined to trust scientists, the experience of snow is concrete and reliable.

While many people may find it hard to connect climate change to their daily experience of the environment, a 2016 study by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that 70 percent of adults in the U.S. believe that “global warming is happening.” However, the same study showed that only 40 percent of U.S. adults believe that global warming will harm them personally, so the question remains: How can the abstractions of climate change science be made more tangible, personal, and relevant?

Even for the majority of U.S. adults who believe that global warming is real, the abstract and complex nature of the problem can make it challenging to fully understand or care about climate change at a visceral level. One difficulty is that other environmental problems are more visible. People can see forests being cut down, a mountain that is being strip mined, or an oil spill in the ocean. But carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is invisible. We can only see graphs or measurements of carbon dioxide levels rising over time.

Observers and experts outside of the field of climatology can help bridge the gaps between intellectual awareness and concrete experience. Rudiak-Gould raises the question, “Can the phenomenon called ‘global climate change’ be witnessed firsthand with the naked senses?” While many scientists “tend to regard climate change as inherently undetectable to the lay observer,” he writes, others, such as anthropologists, environmentalists, and Indigenous communities, “often claim that the phenomenon is not only visible in principle but is indeed already being seen.”

To show that climate change is relevant in people’s daily lives, it is essential to engage with the tangible and concrete evidence that surrounds us. As biologist David George Haskell wrote in an opinion piece in The New York Times this year, “We now experience climate change not only through the abstractions of science, but also through lived experience.” His statement represents a crucial change in perspective. Instead of invisibilism, which diminishes what people can see as potentially false and unverifiable, experience produces the opportunity for people to witness and validate.

Efforts that bring together people from different perspectives and fields are helping to make climate change more visible to a broader public. For example, a project based in Colorado, the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS), set up cameras and compiled time-lapse photos of glaciers throughout the world. Their photos show dramatic glacial retreat over the past decade, including the shrinking Sólheimajökull Glacier in Iceland. Drawing from the strength of a collaboration between scientists and photographers, EIS provides stark, visible evidence of change. Beyond retreating glaciers, there are countless other ways for people to see and experience climate change.

Increasingly, people are seeing flowers blooming earlier and ice freezing later. As summer transitions to fall, the last 80-degree day is occurring later and later. In the Arctic, permafrost is thawing, and in coastal areas, high tide floods are increasing with sea level rise. Farmers throughout the world are contending with irregular seasons, stronger rains, and more severe droughts. In recent weeks, devastating wildfires have been burning in Northern California. As these examples show, the manifestations of climate change are diverse and varied. By witnessing the changes that affect each of us locally, as well as the ones that can be made visible from afar, it is possible to bridge the gaps between scientific abstractions and the world around us.