Protecting Ancestral Waters Through Collaborative Stewardship

When the soul of a deceased member of the Chumash peoples bathes before departing for the afterlife, many say it does so at Humqaq, or Point Conception. [1] [1] The spelling of the place name varies across Chumash languages; Humqaq is the spelling used by the Northern Chumash Tribal Council. According to Chumash generational knowledge, this coastal headland and its surrounding waters, located about 50 miles west of Santa Barbara, California, have been occupied by Chumash peoples and their ancestors since time immemorial. A sacred place for the Chumash, Humqaq also provides important habitat for a variety of plant and animal species, and—if all goes according to plan—will soon be legally protected as part of the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary (CHNMS).

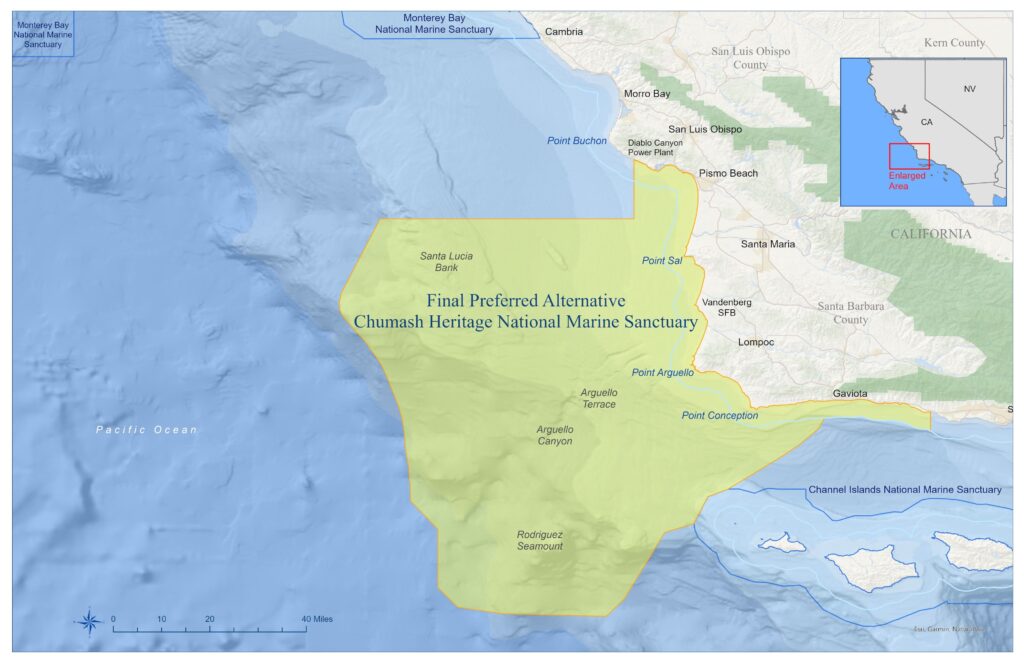

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) completed their final environmental impact statement for the creation of this new sanctuary in September and is poised to issue a designation by the end of 2024. If approved, the CHNMS will be the first marine sanctuary in the U.S. proposed by Indigenous peoples. Importantly, the plan for this sanctuary is that the federal government and Native tribes of this part of California will collaboratively manage the CHNMS to protect the region’s marine ecosystems and cultural heritage.

Members of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, who have led the nomination campaign, argue incorporating local Indigenous knowledge in the management of this sanctuary will ensure the marine ecosystem is not only preserved, but restored. They have partnered with a wide variety of groups, including the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and other Tribes and Tribal organizations, to support this endeavor.

The sanctuary would protect submerged villages and other Chumash heritage sites and the habitat of numerous marine species. These include whales, dolphins, sea otters, turtles, seals, and fishes and the oceanographic features that support these populations. Proponents say the sanctuary would also benefit Native and non-Native human residents by providing areas for recreation, defending against offshore oil drilling and mining, and likely generating hundreds of jobs in tourism and related industries.

The collaborative management plan for the CHNMS is ethically and politically significant, as it recognizes the rights of Native peoples to govern their own lands and waters. As a human ecologist and archaeologist who studies the use and management of natural resources, I believe research supports the claim that a Tribal-federal collaboration could be effective at ensuring the area’s sustainability long into the future—as long as the voices of local Indigenous stakeholders are truly prioritized.

ENSURING SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT

In 1968, ecologist Garrett Hardin published a now well-known article in Science titled “The Tragedy of the Commons.” A “commons,” or “common pool resource,” refers to a shared but finite resource, such as groundwater, fisheries, land, oceans, forests, or even the internet. Assuming groups of people would overuse these resources to benefit themselves in the short-term, Hardin argued common pool resources must be privatized to ensure their sustainable use.

As a thought experiment, Hardin imagined a group of farmers grazing their cattle on a shared pasture. Though collectively the farmers would be better off constraining their use of the pasture for the sake of long-term sustainability, any single farmer would benefit in the short term from letting their own cattle graze unrestricted. Hardin therefore argued that groups cannot be trusted to manage a commons and such resources must be privatized for their own preservation.

Hardin took things further, however, and used this thought experiment about environmental mismanagement to push a dangerous narrative about purported threats facing the U.S. His views on the existential dangers of group behavior led him to advocate for population control, dismantling the welfare state, and explicitly white nationalist policies—all in the name of environmentalism.

Despite Hardin’s continued influence, subsequent researchers have found his work was flawed not only ethically, but scientifically. Chief among these critics was economist Elinor Ostrom, who won the Nobel Prize in 2009 for her work on the sustainable governance of common pool resources. Ostrom conducted a detailed analysis of published case studies from around the world and found many small-scale communities had created ways to ensure long-term sustainable management of commons without the need for either privatization or centralized governmental control.

Based on her findings, Ostrom described a set of principles outlining how local communities can sustainably manage a commons that other researchers, activists, and policymakers have since taken up as guidelines. These include setting clear boundaries concerning access, adapting management to local needs, ensuring all stakeholders can participate in governance and regulation, and scaling up management within nested networks of institutions respected by larger authorities and governments.

COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE CHNMS

Fundamentally, Ostrom argued democratic control by local stakeholders—not privatization or central planning—is key to sustainable management of a commons.

Local stakeholders are often most successful in managing a commons because they have the most to gain and lose from its use or misuse. In the case of the CHMNS, the Native residents of the area are far more invested in the potential success of this sanctuary than is the federal government.

The Chumash have been stewards of these waters—part of their ancestral territory—for many thousands of years. They have been fighting for generations to regain control of the more than 100 miles of coastline and thousands of square miles of ocean that will likely be designated as the CHNMS. The collaborative management of the CHNMS is viewed by the Northern Chumash Tribal Council as part of their broader land back strategy, in which the ultimate goal is the return of unceded private and public lands to the tribes from whom they were taken.

As the Chumash and other Native residents of California will be heavily involved in the management of the sanctuary, the proposed collaborative management plan of the CHNMS to some extent appears to conform to several of Ostrom’s principles.

Per the plan, Tribal members and other Native peoples from this part of California would be able to serve on an advisory council and panel, collaborate with NOAA staff to manage the sanctuary, and coordinate activities with NOAA through nonprofit organizations. An Intergovernmental Policy Council would also be created to interface between NOAA, the State of California, and federally recognized tribes in the area of the sanctuary. This bureaucratic apparatus would permit Native input into governance decisions, ensuring that Native members of the local community could participate in the CHNMS’ management by helping to set boundaries, establish rules, monitor access, and sanction rule violators.

However, the sanctuary would still be controlled centrally through NOAA as an arm of the U.S. government—not locally by Native peoples. NOAA supports Tribal input and collaborative management but not co–management; NOAA would retain the final say in decision-making about the CHNMS.

This deviates from Ostrom’s principles, but given the ways in which Indigenous communities’ needs and voices have consistently been left out of federal land management decisions, this plan for collaborative stewardship represents a significant shift in the right direction. As the Northern Chumash Tribal Council explains, the CHNMS would establish an important precedent for “elevating Indigenous perspectives and cultural values in ocean conservation.”

LOOKING FORWARD

The CHNMS is not the only recent example of joint federal and Tribal management of traditionally Native territory.

At Bears Ears National Monument in southern Utah, a cooperative agreement has been signed between the Department of the Interior, the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the Department of Agriculture, and the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition: a group of five Native Tribes from the area. The details of the final management plan have yet to be decided upon, but the preferred option maximizes Tribal involvement through collaboration in planning, not just back-end consultation. Such a plan aims at more effective management of this monument, helping to reconcile differences between settler-colonial and Native conceptions of land stewardship.

One key litmus test for whether the CHNMS is truly being managed collaboratively will be the potential future inclusion of Morro Bay, California.

In the sanctuary plan, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council originally advocated to include the bay, home to Lisamu’ or Lesa’mo’, a volcanic rock held sacred by the Chumash and Salinan peoples. However, in part because of pressures from offshore wind farm developers, the final environmental impact statement recently released by NOAA excludes Morro Bay from the sanctuary’s boundaries. The Northern Chumash Tribe and three offshore wind developers agreed to exclude Morro Bay for now so that development can continue, but to advocate for its inclusion in the sanctuary in 2025 once the wind farms are constructed. Time will tell whether NOAA agrees to eventually include Morro Bay in line with the wishes of the Northern Chumash.

Though imperfect, the CHNMS management plan is an important step toward a more sustainable and just future. While it could align more closely with scientific consensus on sustainable governance of the commons, it goes further than other marine sanctuaries in ensuring ethical and effective management and the re-inclusion of Native peoples in decision-making processes about their own lands.

Combining Tribal Ecological Knowledge and the scientific insights of Ostrom and others, the CHNMS should serve as inspiration for future marine sanctuaries and other protected lands and waters, both in the U.S. and around the world.

Editor’s note: To support the successful designation of the CHNMS, the Northern Chumash Tribal Council encourages people to follow along with their efforts, donate, or sign up to volunteer.