Conflicting Times on the Camino de Santiago

We brush past each other like ghosts. A woman wearing a visor, khaki shorts, and a large backpack rushes ahead—her hiking poles determinedly tapping their way into the distance.

“Buen Camino,” she nods tersely.

“Buen Camino,” I echo back, watching her disappear around the bend.

“Buen Camino” translates literally to “Good Way.” It’s a trademark pilgrim acknowledgment unique to the Camino de Santiago, a network of UNESCO-recognized pilgrimage routes that span Europe and converge on the Galician capital of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain.

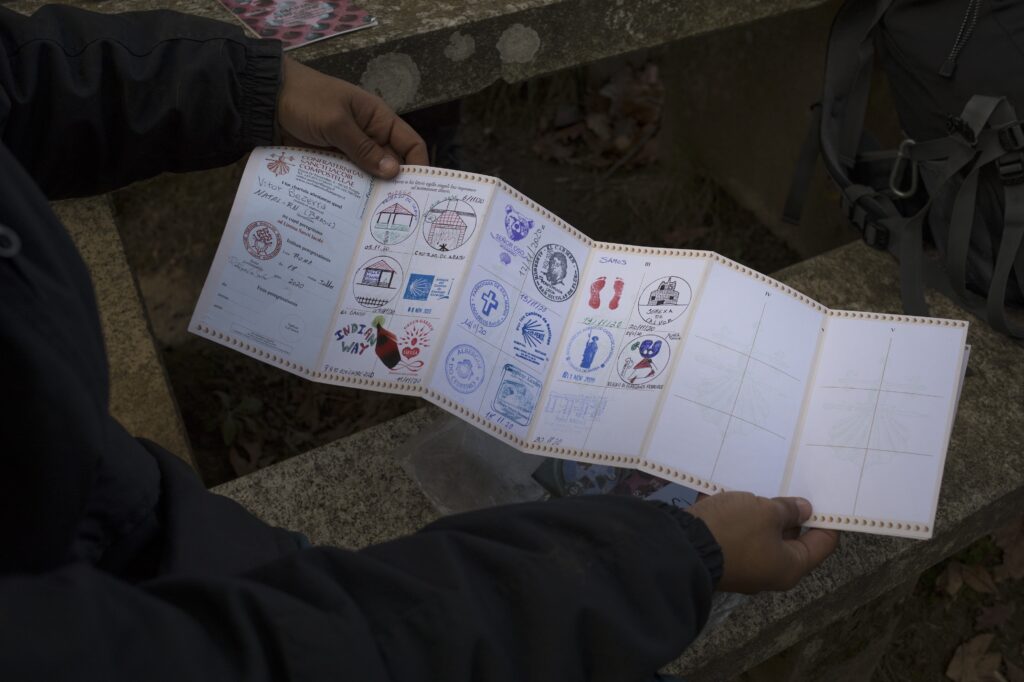

On this day in September, I’m walking the Camino Francés, the most renowned route in the network, along with thousands of other pilgrims. The 500-mile, physically taxing route passes through four autonomous Spanish regions with diverse physical and cultural landscapes. Most people take five weeks to complete the journey, though paces vary. By walking the Camino, I join a history of seekers navigating roughly the same “way” since the Middle Ages.

I first began researching the Camino Francés for my doctoral thesis in anthropology in the summer of 2017. Before that, I walked the route twice as a pilgrim, partaking in its rituals and rites of passage, and coming to know the communities and landscapes like friends. The experiences I had prior to my research remain integral to a site I continually rediscover through evolving understandings of the relationships between people, place, and time.

A few hours later, I cross paths with the same woman who flew by me earlier that morning. “Buen Camino,” I say again.

We sit outside for lunch at a cafe in the small town of Tardajos in Castile y León, Spain—about a third of the way along the route. The early afternoon sun beats down forcibly. This time, the woman is more friendly. She introduces herself as Nancy from Toronto. [1] [1] Names have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Nancy worked in finance before she retired. Like many pilgrims I’ve met, she tells me she is on the Camino to “slow down.” But it does not come easily to her.

For pilgrims on the Camino, time unfolds in unexpected ways. Some describe pilgrimage time as a vortex; others liken it to a tunnel. Conversations open like accordions, and layers of the past and present seemingly collapse. Pilgrims often reflect on the length of moments—their simultaneous expansiveness within a larger journey bound to historical cycles and rituals. Relationships feel more meaningful and sensations—both good and bad—seem more immediate.

Many self-proclaimed agnostic and spiritual pilgrims are not on the Camino to find God, as their Catholic precursors likely were; rather, they are on the route to seek a “good way” through life again. Many hope to flee the fast-paced stresses of capitalistic cadence—lives back home where time blurs together and work takes over. A lapsed lawyer walking his mind away explained his relationship to time this way: “To live well is to live slow.”

Ironically, those who struggle to slow down find themselves judged—or at least teased—by other pilgrims. Since the start of her journey, Nancy’s tendency to race along the route has earned her the nickname “The Hare.” At the cafe, she introduces me to her “Camino family,” or group of hiking buddies—people she convenes with in the evenings after spending days walking alone. I meet Allan from Chicago, Elena from Hungary, and Tom from Canada. They laugh over beers at Nancy’s obsessive need to “beat everyone” to the albergues, the pilgrim hostels where most Camino walkers sleep at night.

“Nancy barely has time to say, ‘Buen Camino.’ Right?” Allan laughs.

“That’s not fair, Al, I’m doing my best. Everyone walks their own Camino,” Nancy responds. She has been in Spain for two weeks—on the Camino for 10 days. It is taking her longer than she imagined to “slow down.”

A waitress comes by, and we order more beers. Time passes.

“Are they coming or what?” Allan asks as another stream of pilgrims pours into the shop.

“Yeah—where are our beers?” Tom looks perplexed.

“I’ll go and see what’s happening,” I volunteer.

Inside the bar-cum-convenience store, a young woman sweats as she struggles to meet the demands of entering pilgrims.

“Ah, las cervezas. Un momento, un momento,” she says, clearly frazzled. Oh, the beers. One moment, one moment.

“No hay prisa,” I respond. “Todo está bien.” No rush. Everything’s fine.

When viewed through the lens of the Camino’s permanent communities, the relationship between pilgrims and time gains an added layer of complexity. Not solely a pathway for pilgrims, the Camino is also a home for many locals, the majority of whom either aspire to or currently make their livelihoods on the waves of hikers passing through their villages and buying wares and food as they walk. For these Camino dwellers, there’s no escaping capitalism, as their daily rhythms speed up to meet the intensifying demands of the tourist economy.

Pilgrims have flocked to the Camino in ever greater numbers in recent years. In 2003, the Pilgrim’s Reception Office for the Camino counted 74,324 pilgrims; in 2023, the number reached a record-breaking 446,039 pilgrims. New hostels have opened to accommodate the influx in passersby, benefiting some locals while disadvantaging others. In some places, the gentrification of neighborhoods has pushed less affluent locals into urban enclaves.

I return to the table outside to update Nancy and her crew on my conversation with the waitress. “She’s doing her best,” I say. “She’s by herself—it takes time.”

“This is by far the worst service I’ve experienced on the Camino,” Allan says.

Nancy looks up and says, “What’s the rush? We’re here to slow down.”

I cannot help myself. “Imagine having to take care of a constant flow of pilgrims. She’s probably exhausted.”

“They’re getting good money out of this, aren’t they? I mean, we’re Americans,” Allan responds, looking at me.

Allan is not the first foreign pilgrim to justify his impacts on the place and landscape with economic exchange. Many pilgrims view their presence on the Camino as a reciprocal benefit for local communities—one that offsets the burdens of tourism.

As I’ve found through my research, however, permanent communities often feel differently. “Buen Camino” has become an increasingly disruptive greeting. Not only does it heighten the pace of daily rhythms, it also equates to noise pollution when rowdy pilgrims pass along the streets at night or parade through towns early in the morning.

Increased numbers of visitors heighten environmental consequences, including soil erosion and waste. In more rain-prone areas of the Basque region and Galicia, Camino pathways erode during the rainy spring and winter seasons. Plastic water bottles, empty chip and energy bar packages, and toilet paper left by disrespectful pilgrims accumulate along the side of the trail. Local farmers often walk Camino pathways after pilgrims have passed, picking up in their wake and clearing trash tossed into surrounding fields.

During a fieldwork stint in Galicia, I found that those living in my barrio directly adjacent to the Camino even refused to utter “Buen Camino,” resisting endorsement of a “good way” they did not share.

As these tensions build, it is hard to know what time holds for the Camino. Massification of the pilgrimage route continues to burden both human and environmental landscapes.

People on the route to “slow down” frequently fail to recognize the consequences of increased travel on their chosen retreat site. Recently, I spoke with a woman who had walked a portion of the Camino route with an elitist group of wellness seekers out of Los Angeles. Members of The Ashram turned to the Camino for a mindfulness fix. They stayed in hotels and shipped their bags ahead. They may have found a personal slowness and a form of rejuvenation, but at what cost for the sites and communities they passed through?

Back at the restaurant, the beers finally arrive at the table. The sun is significantly lower in the sky than when we sat down. We have eaten several bags of chips. Allan has finally calmed down.

“It’s about time,” he winks, taking a drawn-out sip.

“Careful,” Nancy winks back. “Time has a way of getting away from you.”

Inside, the lights dim. It is time for siesta. No more food. No more service. For two hours, the blinds will close. The waitress will eat and rest. Pilgrims will come and go, dismayed that there’s nowhere open to order beer. Again. And time will hang suspended.