When a Message App Became Evidence of Terrorism

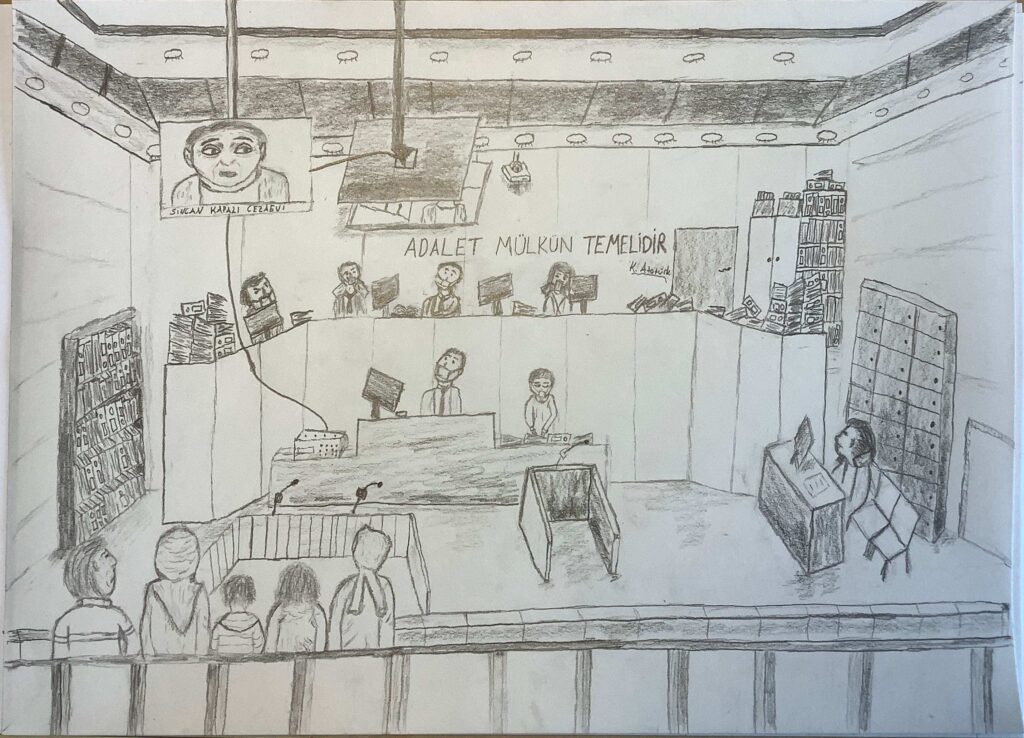

Summer of 2017. Ahmet, a 22-year-old university student, stands trial in a Turkish criminal court. [1] [1] This name has been changed to protect this person’s privacy. He is accused of being associated with the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETO) or Fetullahçı Terör Örgütü (FETÖ) in Turkish. This is the name the Turkish government uses to denote the Islamic network led by the U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gülen.

No witnesses or physical evidence tie Ahmet to the Gülen network. The basis for his charge is that his cellphone connected 317 times to the server of ByLock, an encrypted message application for smartphones. As the prosecutors see it, ByLock exclusively serves the Gülen network. They equate any data related to the app with a global terrorist conspiracy.

Ahmet asserts that his phone connected to ByLock without his knowledge. And his phone records confirm that he didn’t use the app to send any messages.

The court sentenced Ahmet to six years and three months in prison.

His case was not unique. Between 2016 and 2021, the Turkish state investigated around 1,800,000 people from diverse political backgrounds on terrorism charges. Most of the incriminating evidence involved records of communication signals, social media posts, and digital data stored on phones or memory devices. Hundreds of thousands of these people stood trial. Others have lost their jobs, been shunned by their communities, or died by suicide.

I am an anthropologist who, over three years of research, has observed more than 700 terrorism hearings and interviewed dozens of digital forensics professionals, lawyers, defendants, judges, and state prosecutors. In many trials, those who occupied defendant docks were not dissidents but people typically supportive of the Turkish state: former military members, police officers, or conservative and pious individuals.

Some international news media have portrayed this crackdown as textbook tactics of an authoritarian government. The nationalist-Islamist coalition of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has indeed oppressed and silenced dissidents through both legal and nonlegal means.

As legal professionals treat digital metadata like smoking gun evidence, the scope of terrorism trials has swelled uncontrollably.

But that is not the full story: These individuals were criminalized by a confluence of state-spun narratives about the pervasiveness of terrorism and a court system that awards digital data immense weight. As legal professionals treat digital metadata like smoking-gun evidence, the scope of terrorism trials has swelled uncontrollably—offering a lesson to nations worldwide about the risks of digital evidence in criminal justice systems.

UNLAWFUL APP

When Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002, the Gülen network was already controlling several media outlets, schools, banks, and corporations. Over the next decade of AKP rule, the Gülen network had its golden age. The Turkish government encouraged Gülen members to staff key positions in the judiciary, police, military, and other parts of the state bureaucracy.

But a 2013 corruption scandal transformed covert conflicts between the AKP and Gülenists into an all-out war. Former allies became sworn enemies. Erdoğan’s government redefined the Gülen network, first as a parallel state structure and then as the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization. The government also dismissed and prosecuted prominent figures allegedly loyal to Gülen.

On July 15, 2016, a group in the Turkish armed forces launched a failed coup, which Erdoğan’s government blamed on the Gülen network and its leader Fethullah Gülen. After the attempted coup, counterterror operations started to target ordinary people who were associated with the network’s institutions in some aspect of their lives. The new state narrative turned all followers of Gülen into a group of fanatics who conceal their real identities and recognize no morals in their unrelenting pursuit of power.

However, rooting out members of such an allegedly elusive but pervasive group would be nearly impossible using traditional investigation tactics. So, the government turned to different types of digital evidence—including an encrypted message application called ByLock: Secure Chat & Talk.

Mehmet Yılmaz, deputy chairman of the Supreme Council of Judges and Prosecutors, presented ByLock as the “strongest evidence” of FETO membership. Made available on Google Play, the Apple app store, and other online platforms between 2014 and March 2016, the publicly available app was downloaded over 500,000 times by users all over the world. But based on some deciphered messages and the location of IP addresses, the Turkish National Intelligence Organization argued that Gülenists designed and exclusively used the app. [2] [2] Internet protocol (IP) addresses are unique numbers assigned to each gadget connected to the internet. For example, while writing this footnote, my IP address was 168.150.104.237.

Independent forensic examiners who I interviewed acknowledge that most users are indeed Gülen sympathizers, and designers had likely connected with the network. But, to them, ByLock possession does not prove FETO membership.

The “evidence” has two major problems: The intelligence organization and prosecution defined anyone who connected to or downloaded the app as a ByLock user even if they did not send any messages. Second, most messages were quotidian conversations, such as sharing cooking recipes or religious praises.

DOUBTING DIGITAL EVIDENCE

Digital forensic examiners estimate that the Intelligence Organization’s assessment of ByLock initially made around 215,000 people terrorism suspects.

Judges started to sentence anyone whose phone connected to the ByLock server, regardless of whether messages were sent. Those I interviewed told me only digital data could uncover the conspiracies of a deviant religious group that conceals itself through lies and disguises. They also assumed digital data extracted from surveillance databases and the ByLock server could identify individuals in the internet network.

There are reasons to doubt such a logic can deliver justice. In 2017, independent digital forensic examiners and lawyers discovered thousands of phones connected to the ByLock server without knowledge of their users. This revelation forced the prosecution to drop charges of 11,480 suspected ByLock users and to acknowledge the existence of “errors” in digital investigations.

Listen to the author’s podcast for more: “The Problems of Digital Evidence in Terrorism Trials.”

Disputing the ByLock evidence, however, came with a cost, as my interlocutors explained: Pro-government media actors organized smear campaigns against independent experts through social media platforms and news agencies. These experts received death threats through unidentified phone calls. One public defender was dismissed from his job.

Despite the intense pressures, a handful of experts continued to emphasize the absurdity of linking all ByLock traces to terrorism. They asserted that the country’s internet infrastructure makes it impossible to identify individual connections to ByLock. Ahmet’s internet provider, for example, distributed the same IP address to thousands of clients. [3] [3] If dynamic IP addresses are used, they can change. Also, users can replace their actual IP addresses through virtual private networks (VPNs), which mask a user’s location, identity, and activity. So, the connection records associated with Ahmet’s phone may have belonged to someone else.

Besides, even though many people did use the app and sympathized with the Gülen network, that does not mean they are terrorists. Millions of people, including prominent government actors, had ties with Gülen for religious reasons, employment, or political influence.

The judges I interviewed know these issues. They still use “ByLock records” as evidence. “In the matters of terror, we sometimes sacrifice human rights,” one judge told me.

INNOCENT and RUINED

Given Gülenists’ past partnership with the Turkish state apparatus, it is unsurprising that few opposition leaders foregrounded dubious terrorism charges in their public speeches. Opposition parties, such as the Republican People’s Party, agree that the deadly conflict between two Islamic movements is ruining the country. They do not want to associate with Erdoğan’s government, the Gülenists, or any alleged associates of the Gülen network.

But the prominent actors of the network make up a small proportion of those on trial. Rather, these trials predominately incriminate likely innocent students, teachers, doctors, and other ordinary citizens.

Six months after Ahmet completed his jail time, in September 2023, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled a judgment that called into question all ByLock trials and other digital investigations carried out after the attempted coup. The ECtHR found that the Turkish state violated the rights of a teacher whose case mainly rested on alleged ByLock usage. In the judgment, the court also highlighted another 100,000-plus similar cases.

Since the ruling, Bylock has rarely been used as evidence in new trials.

But for those already prosecuted, like Ahmet, many are unsure how to face the legal uncertainty that has haunted them for years. Some have already served their jail time. Others sit in prison. And many more—who were acquitted or did not stand trial—have lost their jobs and dignity.

The ByLock case exemplifies how state authorities can ruin people’s lives under the banner of counterterrorism—and normalize doing so. Such violence manifests itself in many forms and places: excessive government surveillance in the U.S., Israel’s bombing of civilian areas in Gaza, or, as in Turkey, the production and manipulation of forensic evidence. We should call out and reject political systems that arbitrarily make our lives precarious and disposable.