What a “Safe and Dignified” Burial Means During a Pandemic

A few months into the pandemic, a friend from Cameroon, where I’m from, sent me a video of a news clip. The video starts with shaky footage of a small crowd of people yelling and running out of a drab building onto a city street. They’re carrying what appears to be a human body.

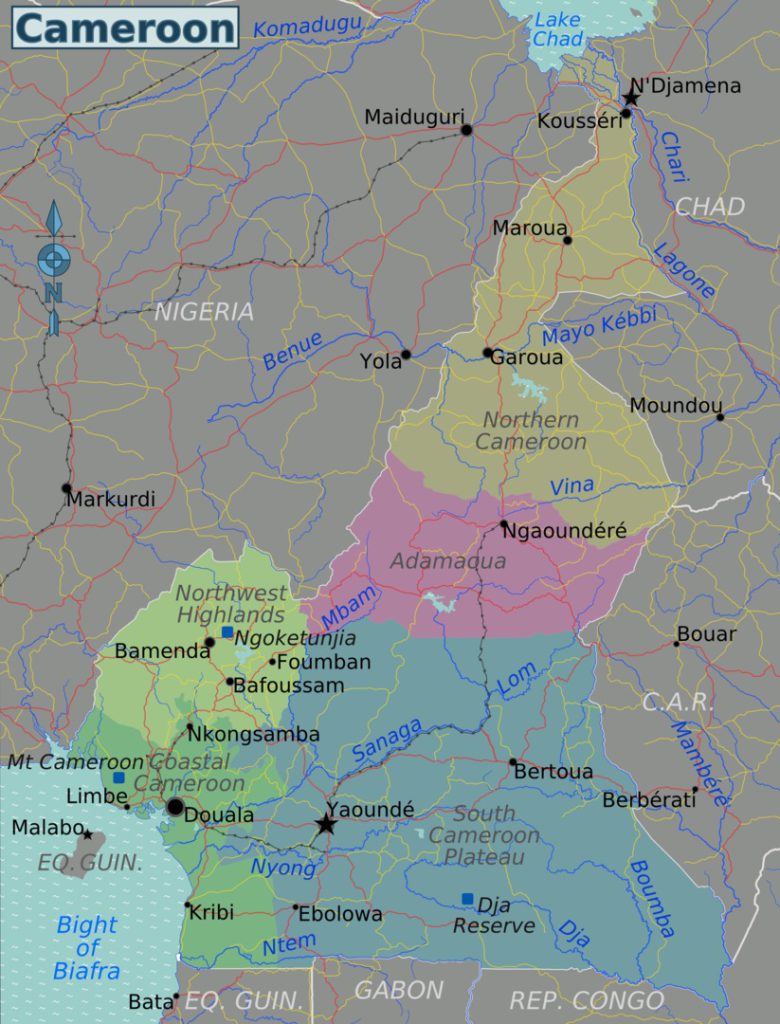

A voiceover in French explains that the body, wrapped in white cloth and carried on a green mattress, belongs to a man in his 70s named Nyamsi Maurice, who died after several days in the hospital. The scene takes place in front of the Clinic Marie O, a medical facility located in the neighborhood of Bali in Douala, the largest city in Cameroon.

The video cuts to a young man identified as the son of the deceased. (After the family fled with the body, journalists arrived at the scene and began interviewing bystanders and clinic staff.) The young man in the video begins telling his story: “We brought our dad to the hospital because he had a stroke.”

He goes through a long list of exactly how much the family paid for their father’s medical treatments—a total of more than 1,000,000 CFA francs, or approximately 1,500 euros, for hospitalization and various tests. He explains that the hospital staff told the family the man’s condition was stable, but in order to see him, they had to pay.

The son’s rage and disappointment at the medical staff feels palpable. “Four days later, our dad died,” he yells at the camera. The staff told the family that the man died of coronavirus, but the son denies this version, showing his father’s medical file as evidence.

The video then cuts to an interview with the doctor in charge of Nyamsi’s case. The doctor, sitting in his office wearing a face mask, responds with a detailed clinical history of the patient. He explains that the cause of the diagnosed stroke was coronavirus; a chest scan showed a COVID-19–type pneumonia. He says, “We tried to treat this man for four days, warning the family that his condition was extremely severe and contagious. He died this morning.”

The doctor adds flatly, “We understand the emotions of the family because they would prefer to bury the man in his village.” But the hospital, he says, followed public health protocols.

After the family stole the corpse, the hospital called the police and military to intervene, although the family managed to get away before authorities arrived.

I later learned that Nyamsi’s family, who are from the Bamileke region of western Cameroon, were taking his body back to their ancestral village to be buried according to traditional funerary practices. They did not want their father to be promptly buried in a cemetery in Douala, as public health protocols would have required.

The sensational video of this incident got picked up by the popular Cameroonian entertainment and news site Beta Tinz. It spread widely across Facebook and Instagram, and my Cameroonian friends posted the video in their WhatsApp statuses.

Why did the family refuse to accept COVID-19 as the cause of death for their late kin? What drove them to steal the corpse?

As a medical anthropologist who has studied the behavioral practices and cultural conflicts that arise during infectious disease outbreaks, I found myself thinking about these questions a lot after watching the video—and wondering what could be done differently to prevent this kind of situation from happening again.

Those in health care are facing a difficult job during this pandemic. Not only must they treat complex infections, but they have to address widespread misinformation and resistance from families and loved ones who may disagree with the diagnosis of COVID-19 or the safety protocols put in place by public health officials to mitigate against the spread of the virus.

These tensions become heightened when a person dies. Governments around the globe have put restrictions on handling the bodies of those who have succumbed to the virus. Protocols involve wrapping bodies in plastic and disposing of them quickly in designated burial sites. Consequently, grieving loved ones find themselves stripped of wakes, funerals, and other sacred ceremonies that honor the end of a human life.

According to the World Health Organization, as of January 14, Cameroon has 27,336 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 451 deaths.

However, many people in Cameroon are suspicious of these numbers. On social media and in person, conspiracies abound. People claim, for example, that medical doctors are creating fake records of COVID-19 cases in order to qualify for the emergency funds that have been made available from the government and from nongovernmental organizations. (Such conspiracies are not limited to Cameroon; in the U.S., President Donald Trump stoked similar rumors about doctors inflating COVID-19 death counts.)

This widespread distrust of health care workers and public health protocols is not new. In 2015, I teamed up with another medical anthropologist, Merrill Singer, to research the social factors surrounding the spread of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. We found that many local residents in Cameroon openly defied public health guidelines, in large part because of widespread misinformation and mistrust of government officials who were seen as corrupt. For example, many residents continued eating bushmeat even though officials claimed that the practice could spread the virus.

Public health officials must find ways of balancing local knowledge, ancestral burial customs, and global health protocols.

As the pandemic continues, public health officials in Cameroon are learning that responses to COVID-19 must also take into account culturally specific responses to death and disease, which may not fit neatly with public health protocols.

According to a recent Associated Press article, confrontations between grieving families and public officials in Cameroon are currently on the rise. Journalist Emeline Fonyuy writes that such resistance is a clear indication of “the strong influence that ancestors still play in people’s daily lives in this Central African nation.”

In the case of the video described above, both factors came into play: the family’s mistrust of the Cameroonian health care system combined with their desire to follow Bamileke ancestral ways of mourning and honoring the dead. In the end, they saw no choice but to snatch the corpse of their late father and flee from the hospital.

According to posts and reactions to the video on social media, many people empathized with the family’s decision to steal the body. Some agreed with members of Nyamsi’s family who claimed that his death from COVID-19 was a hoax. Other viewers saw his death as an example of the incompetence of the health care system in Douala. (In 2016, protests erupted in the city when a pregnant woman died, possibly due to medical negligence.)

Regardless of the ultimate cause of death, Nyamsi’s family felt strongly that their father should not be buried quickly in a gravesite in the city, as public health officials were insisting. As the patriarch of a high-ranking polygamous family, his death would traditionally be marked with elaborate funerary rituals. Moreover, the family felt that burial outside of their ancestral lands in western Cameroon would provoke the wrath of the soul of the deceased and of other deceased ancestors. According to anthropologist Beaudelaire Kaze, living Bamileke people must demonstrate piety toward their dead kin.

In other words, without a corpse, the family would have been unable to pay the deceased a fitting final tribute.

Cases of body snatching during the COVID-19 pandemic have occurred in other countries too. In Indonesia, for example, some Muslim family members have reportedly stormed hospitals or stopped ambulances to take away the bodies of their loved ones who were set to be buried under virus protocols. These “body snatchers” went to these extreme measures so that they could follow Islamic funeral practices.

For Muslims, as researchers have pointed out, “death is only a transition between two different lives.” To make that passage between lives, Muslim bodies must be properly bathed from head to toe and then wrapped before being buried. Similarly, West African religious philosophies see death as a continual process that involves specific rites of passage linking the living and the dead.

So far, authorities have taken punitive measures to handle cases of body snatching: Hospitals have addressed the problem by calling for more security, and some officials have treated loved ones who steal corpses as criminals.

These punitive measures to curb the spread of the virus do not always work—and they may end up jeopardizing public health mitigation efforts in the short- and long-term. Instead, public health officials must find ways of balancing local knowledge, ancestral burial customs, and global health protocols.

The expertise of trained anthropologists can help people navigate these conflicts. During the West African Ebola epidemic from 2014 to 2016, anthropologist Sharon Abramowitz pointed out that anthropologists could contribute valuable, systematic observations to help bridge different kinds of perspectives and understandings of the world and of mortality. With their deep familiarity with specific communities, anthropologists might be able to anticipate why mourners would snatch a body or become violent during a funeral.

During the Ebola epidemic, when health workers faced resistance from bereaved families who were denied access to the dead bodies of their loved ones, anthropologists intervened. They helped craft new protocols and standards for the “safe and dignified” burial of the dead. Public health officials and local communities accepted these changes because the new burial procedures synthesized scientific and cultural values that mattered to all the parties involved.

While maintaining public health standards and saving lives remains a top priority, those who have died from this pandemic also deserve to be buried in a way that respects and continues time-honored customs. And the living need these rituals, too, in order to process their grief and loss in a way that makes sense to them—and to their ancestors.