Finding Our Way Forward—by Remembering

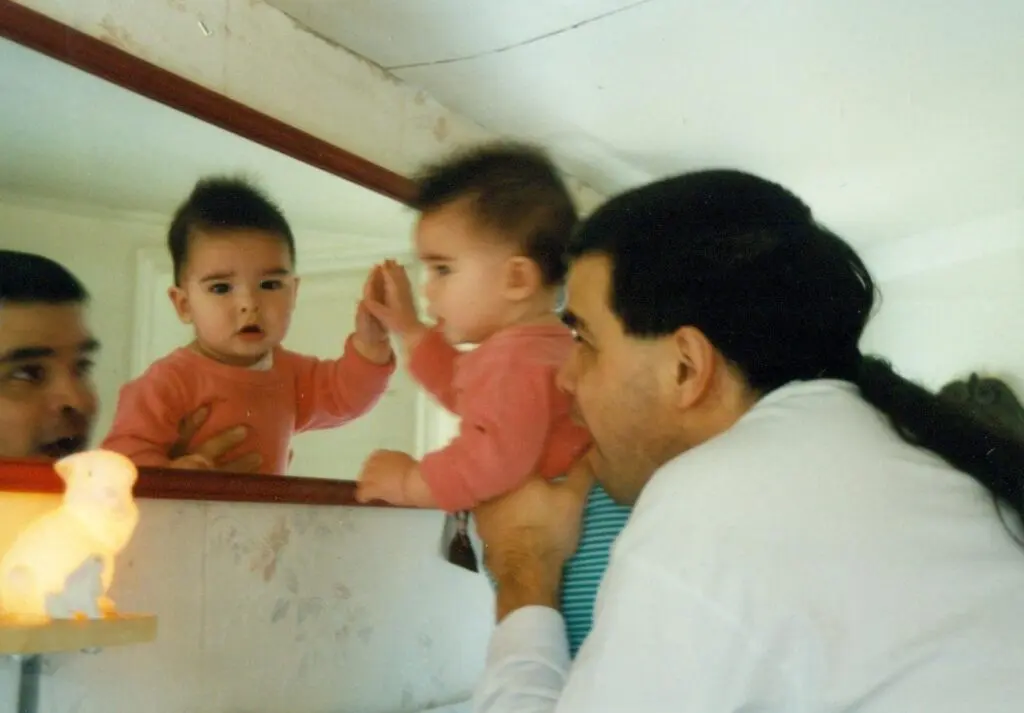

Who should I be today?

I ask myself this question in the mirror of my undergraduate dorm room. Not aloud, of course. That would defeat the whole point. The answer isn’t for me.

I leave for class early, saving enough time to sit outside by the anthropology building and watch people go by. I chose Western Washington University for two reasons: the relatively cheap tuition and the trees that line the entire length of the campus. They remind me of who I still am.

I find my patch of grass and sit cross-legged in a spot of shade. Soon I notice they spot me. I can usually tell from how they walk in pairs, searching for that one kid sitting alone. The young man and young woman, both with fair skin and nice clothes, approach me.

“Hi there! Mind if we chat for a bit?” the woman asks me.

Does someone teach them to start conversations like this? I wonder. Out loud, I play along. “Sure thing!” I scootch over to share my shade with the two of them.

“What are you studying?” the man asks.

I pause for a moment. It’s still early spring, so my skin hasn’t darkened enough for them to see my ethnicity in the stereotypical ways yet. Who should I be today?

I decide to be brave. “I’m studying archaeology, specifically zooarchaeology,” I say.

“Oh, I love dinosaurs!” the man responds.

Never heard that one before. “Me too!” I say. “That’s paleontology, though. Archaeology is the study of our human ancestors. Zooarchaeology is the study of their relationships to animals.”

“Oh cool, what interests you in archaeology?” the woman asks. It’s an innocent question, one I get asked a lot. Doesn’t matter, though. My heart rate goes up. Am I still in the shade? It feels hotter.

“Well, I’m Yup’ik, Native Alaskan, but I grew up here in Washington state. I wanted to learn more about how my ancestors lived and who I am.” Time to see if that was the right choice of who to be.

“Wait, you’re Native American?” she asks. “I thought you were all killed off?”

I can’t tell if my heart rate has stopped or sped up.

Did she actually just ask me that?

Are the trees too far to run to?

I think I made the wrong choice.

I don’t know how much time passes. Finally, I make the conscious decision to look at both their faces.

They’re smiling.

“Uh, nope. Still here, always have been, always will be.”

“That’s great!” the man says. “I thought you were all from Montana.”

No idea where he got that from.

“There are folks from everywhere, including here, and wherever you’re from. Where are you from, by the way?” I ask. Be nice. They just didn’t know. They weren’t the ones who killed us.

“We’re from Canada, actually! We’re on a mission. Do you believe in God?” he asks me.

I already knew they were missionaries by the way they walked together, books in hand, no backpacks. They proceed to tell me why I’m going to hell and how they can save me because being spiritual and agnostic and god forbid Indigenous is not good enough.

By the time they’re done with their spiel, the sun has moved on, and the shade is gone. When I get up to leave, they follow me. I tell them I have class, which is conveniently true. We exchange pleasantries and say we enjoyed the conversation.

As I walk into the dark, cool anthropology building, I remember the stories my elders told me of when the teachers at the Christian boarding schools and orphanages would beat them for speaking Yup’ik. I remember how their names were taken, their siblings separated from them. I remember other things, too, but I quickly bury these thoughts because my day has only just started.

Some days I don’t get to decide who I am.

I find a seat toward the back of the classroom, but not the very back. It’s one of those chair-desks that are awkward to sit in even for most able-bodied folks. The sun dapples through the shades and lands on the old-school black chalkboard at the front. A couple of the students are arguing in that quiet academic way you see on campus that’s mostly about outsmarting each other.

I like the professor for this class. She knows my name, and she has personal connections to Indian Country even though she isn’t Native, so that’s a plus. I feel safer, maybe? She walks into the room and sets her bag on the table in the front. Today’s topic: the effects of globalization on Indigenous people, starting with the Ju/’hoansi people in modern-day Namibia and Botswana.

I remember who I am—and take strength.

As the professor pulls up the slides to begin her lecture, I hear one of the arguing students say, “But it’s just fun, we aren’t doing anything bad.

As I listen in a little closer, I realize they’re debating everyone’s favorite controversial topic: headdresses worn by white people. Mierda.

I speak up. “What do you think you’re talking about? It is not OK, in any world, or place, to mock Native people.” They can tell I’m angry from my tone, but I’m careful not to raise the volume.

“But it’s not like we’re hurting anyone,” one of the arguers says.

“But it does hurt. It hurts me.” I brace myself for her response. Here it comes.

“Why would it hurt you? You’re white,” she says.

The other person steps in. “He’s Mexican.” The class looks at me, evaluating the color of my skin, my facial features, my dark hair, my hazel-green eyes. I look toward the professor, who stares back at me. Go on, her eyes seem to say.

Does she think I’m enjoying this? Get me out of here!

I try standing up but forget I’m in one of those awkward desks and sit back down. Now I’m embarrassed and angry. I feel my collarbones start to heat up again.

“I’m Yup’ik Native Alaskan, Mexican American, Irish, and Scottish. So I’m all of those,” I say. Is that enough? Do I need to tell the stories to prove it?

“Well, it doesn’t make any sense why you would be offended,” the student says to me.

She’s kind of right. My people don’t wear warbonnets. But I still feel a kinship to all Native people, and the conflating of our cultures makes everything feel personal, for better or worse. I file that thought away for my own personal investigation later.

“It doesn’t matter if it makes sense to you,” I say. “You are on this land. Your ancestors committed genocide for you to be here. The least you can do is show respect.”

The conversation goes on like this for another 20 minutes. But we aren’t getting anywhere. Eventually, we stop, and the professor says something about the value of discourse, then continues with a shortened version of her lecture.

I guess the class got to see firsthand what it’s like to be mixed race and Native instead of reading about it in the textbook.

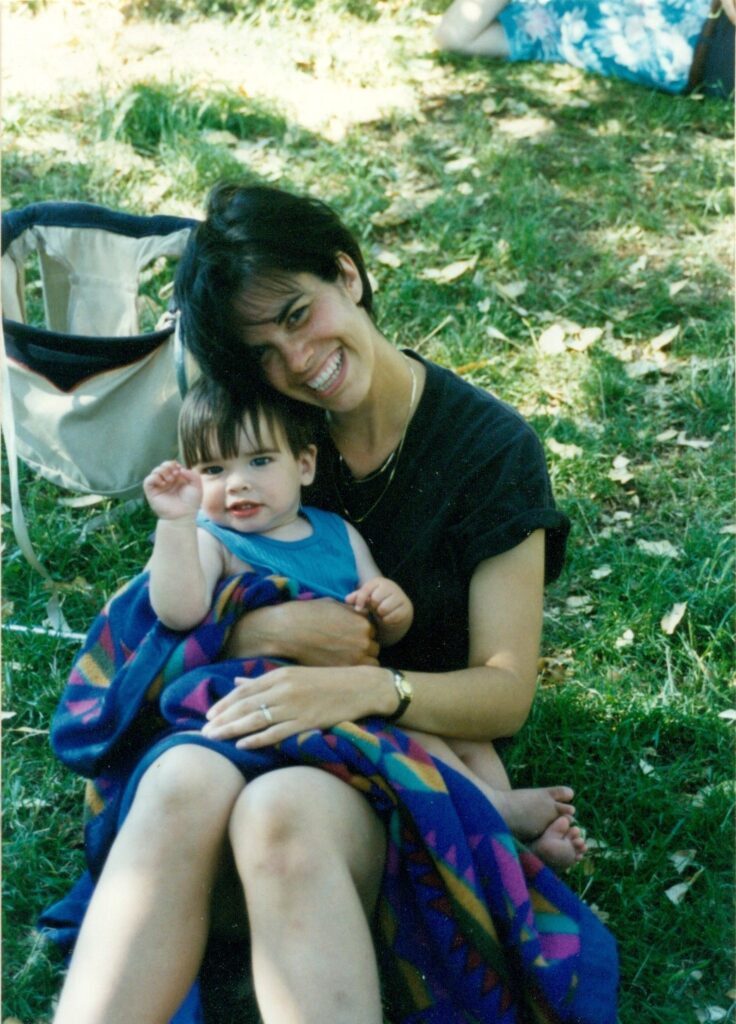

I space out. I remember the “crying Indian” ad, the movies where howling “savages” were killed by the hundreds, the names I’d get called, and the sports mascots that so frequently mock our peoples. [1] [1] The ad, which featured a Native person crying with the goal of raising awareness for environmental issues, has now been retired from widespread circulation. I remember the stories my parents and grandparents shared, and the ones my life has written on its own of the struggles of colonization. But I also remember the tamales my mother would make me as I was growing up, the fresh corn ones with the poblanos and cheese, and the tall maple trees I climbed with my brother, and the salmon bakes during Chief Seattle Days, and my love for Irish folk music. I remember who I am—and take strength.

Flash forward a few years. Grad school. I look in the mirror in my sunny bathroom in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This time I don’t ask myself any questions. I feel at ease with myself as I bike to campus.

I settle into my chair toward the back of the classroom. I’m not trying to hide now; I’m joining my Pueblo and Diné friends sitting there.

Today we’re continuing our extended learning about Chaco Canyon. It’s a fascinating area in New Mexico. The place is a testament to the strength and longevity of Native connections. I think of how Native people would walk hundreds, even thousands, of miles through jungles and deserts to come to this sacred place.

“One of the most stunning and debated elements of the roads in Chaco is their straightness,” our white professor tells the class.

One of my Puebloan friends leans over to me. “I know why it’s straight. My elders told me,” he says, chuckling lightly. He doesn’t tell me, though. Some stories are only meant for Pueblo people.

I understand. Some stories are only meant for my family.

After class, I walk to a warehouse where the university keeps archaeological remains: boxes full of pottery sherds, dirt, animal bones, and stones. The shelves stretch 30 feet in the air and 100 feet long.

When I first started working in a zooarchaeology lab as an undergrad, I took solace in the daily task of sorting bone fragments by fish, mammal, and bird. People don’t think bones can talk, but in zooarchaeology they do—if you know how to listen. The bones tell many stories, such as what a human or animal relative ate, where they went, and how far they traveled.

My mentor, who ran the lab, taught me the best way to learn how to identify bones was to spend a lot of time with them. Eventually, you start to grasp the stories they hold. A small ridge tells you the bone was likely attached to the tendon of a strong animal. Blob-like formations (we call them “pathologies”) indicate an animal had arthritis and may have struggled to move. The rings in a seal’s tooth whisper the age when they died. Different oxygen isotopes buried in turkey bones hint at whether the animals drank from puddles or were given water from humans.

Today I meet my friend at the warehouse to start working on a box of pottery sherds and bone fragments. We rehouse the old, falling-apart paper bags and put the items in new plastic bags with proper labels. We call these times together our “Indian Power Hour,” on account of how much we complain and how much better we feel after we’ve shared things we’ve kept in for so long.

“Why are we in anthropology classes learning about ourselves?” she asks rhetorically. We both know it’s because it’s the only way we can get jobs. She wants to work for the national park system; I want to work in museums.

“Yeah, and our teachers are white, but we teach the other students through our stories,” I add.

“Just wait until they hear the real truth,” she says, laughing.

I laugh, too, and our conversation moves on to motorcycles and upcoming road trips into the mountains.

I remember how far my ancestors had to travel for me to exist. Some of them came from Mexico, others from Alaska, Ireland, and Scotland. All of them are here, with me. I remember how long it took me to stop asking who I should be and instead say, “Yes, I am, and I am also—” instead of “No, that’s not who I am.”

I remember the forest and the friends I grew up with. I remember fishing with my father along the side of the sea. I remember the stories I was told of my ancestors seal hunting, of palraiyuk, of mom’s cow friend named Blondie. The stories of my dog, the bird I saved stuck in a fence, and all the other animal relatives I’ve had the joy of conversing with.

I remember how far we have to go, as a nation and as a world. As individuals. But I remember to look back on the stories our human and nonhuman ancestors have left us. By remembering, we can find our way forward in a good way, as the elders say.