Confronting Anti-Blackness in “Colorblind” Cuba

I sat waiting for Yudell to finish his shift at the paladar, or small-scale private restaurant, in the central Vedado neighborhood in Havana. [1] [1] All names of interviewees have been changed to protect their privacy. I’d already interviewed a few of the workers there. As I bided my time at a corner table on the outdoor patio, two of the waiters began to tease Yudell, yelling across to me, “Don’t believe what he says! He will probably tell you that he is Negro because he is a racist!”

Yudell timidly looked at me across the patio and chuckled. Growing up Cuban American, I had been to Cuba on past occasions to visit family, but this time I was there to conduct ethnographic interviews on processes of racialization for my dissertation in anthropology. I knew from experience that I had to tread carefully when entering conversations about race in Cuba.

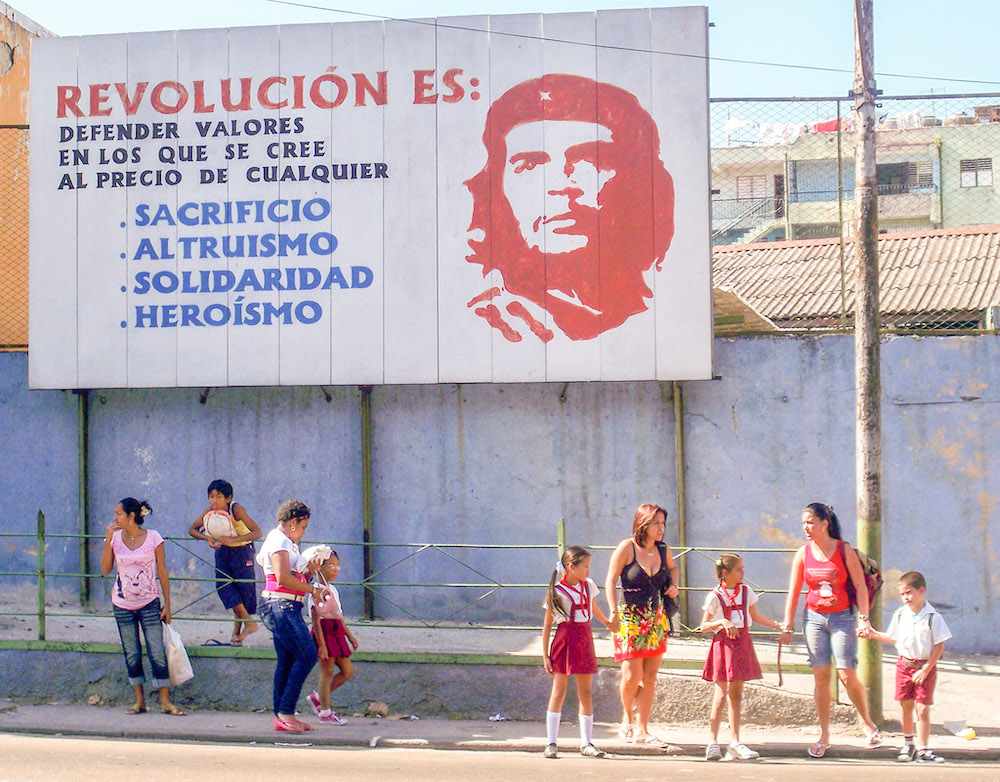

In Cuba, a place where the revolutionary Communist government has claimed to have eliminated racial inequality, directly speaking of race is more than taboo; it is counterrevolutionary.

When we sat down for our interview a little later, Yudell proudly described himself exactly as his co-workers had said he would: “I am Negro” (a Black man). We talked about the persistence of colorism in Cuba, a system of discrimination based on skin color. Yudell chose not to self-identify as a Mulato (a mixed-race person) or a Moro (a dark-skinned person with a thin nose and “good hair”), since he saw such taken-for-granted racialized categories as a way for individuals to distance themselves from Blackness.

Yudell’s self-identification, in other words, served as a form of protest in a society that perpetuates anti-Blackness while claiming to be “colorblind.”

Anthropologists point out that even though race has no biological or genetic basis, racialized identities are socially real. In Cuban society, even though people may claim not to see color, in practice through ranking and valuing an intricate combination of skin tones, hair textures, nose shapes, eye colors, and so on, they produce and maintain dozens of informal racialized identities.

The myth of racial equality in Cuba has become even more untenable recently. This summer, Cubans have taken to the streets in major cities all over the island to demand liberty and denounce economic hardships exacerbated by the pandemic. Afro-Cubans, who have been less likely to benefit from the reforms that have reshaped the Cuban economy since the 1990s, have largely spearheaded these demonstrations. To say these protests are rare is an understatement; in Cuba, where merely criticizing the government can land people in prison, the last large-scale protest occurred in 1994.

Yet, even in the recent protests, explicit discussions of race are noticeably absent from most calls to action. Meanwhile, in Cuban family settings, the focus of my research, race is often openly discussed, but racial inequality is not.

So, why does racial inequality remain so difficult to name in Cuba?

Part of the answer lies in nationalist notions of mestizaje, or racial mixture, that make racial inequality difficult to discuss throughout Latin America generally. In Cuba, the narrative goes, everyone can trace their roots to a mixture of African and Spanish blood. To be Cuban is to be Mestizo (racially mixed).

Cuba’s national identity as a place of racial mixture and harmony has a long history, but these ideas were reshaped and came to be closely tied to the state’s revolutionary communist politics after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Fidel Castro and his government championed social and racial justice in the 1960s, during a time when Jim Crow segregationist laws were just starting to be dismantled in the U.S. By 1962—two years before the U.S. passed the Civil Rights Act—Castro claimed to have eradicated racism in Cuba.

Castro exploited ongoing racial tensions by denouncing the “race problem” in the U.S. and inviting African Americans to visit revolutionary Cuba. This narrative of international Black solidarity became even more pronounced during Cuba’s involvement throughout the 1970s and ’80s in anti-imperialist and revolutionary struggles on the African continent, including Angola’s War of Independence and the fight against apartheid in South Africa. Tellingly, when Nelson Mandela was released from prison, one of his first trips was to Cuba, where he met with Castro to thank him for being “a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people.”

But Cuba’s international fight for racial justice masked the continued inequality on the island. Since the revolution had supposedly eradicated racism, discussions of racial inequality were deemed divisive. Castro’s government dismantled race-based organizations and clubs—including clubs where Afro-Cubans had historically gathered to network and advocate for their communities.

This façade of racial harmony would soon come undone after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, when Cuba entered an economic crisis known as “El período especial en tiempos de paz” (special period in times of peace). In response to the economic crisis, Cuba welcomed mass tourism and introduced a small private sector largely funded through remittances sent by family members abroad.

These changes have reshaped economic relations on the island and revealed the stark racial disparities that had never really gone away.

Today racial hierarchies persist in daily life. But individuals who speak out about racial inequality may be socially policed—as Yudell was—or face more serious consequences.

In the tourism sector, job ads often use racially codified language, such as: “Seeking employees with buena presencia.” As everyone in Cuba knows, “good presence” refers to those with whiter skin tones and straight hair. These requirements limit access to tourism jobs for people with darker skin tones and reinforce the constructed superiority of Whiteness.

But it’s at home where most Cubans first learn of racial discourses and hierarchies—and their place within them.

Cuban families are incredibly racially heterogeneous, and even biological siblings may be racialized differently from one another and their parents. Family members commonly compare and constrast physical features, such as distinguishing between pelo malo (“bad hair,” referring to coarse, curly, or kinky hair) and pelo bueno (“good hair,” referring to straight and fine hair).

For some people, this means hearing denegrating comments about their appearance from their own immediate family members. Some may even internalize racial hierarchies.

In Cuba, directly speaking of race is more than taboo; it is counterrevolutionary.

This was true for Alina, one of my interviewees, who was born in Guantanamo in the early 1960s. One of eight siblings, Alina told me confidently that she happened to “get the pelo bueno.” The rest of her siblings, she said, were Mulato Jabao—a term that refers to people with stereotypically White, European features but with visible African ancestry. They had “greenish-bluish eyes,” Alina said, but then gestured disapprovingly to show they had “bad hair.”

Alina was not only proud of her “good” hair and light eyes, she considered herself one of the “White” siblings—and separated herself from the others whose darker skin made them Mulato.

As we spoke, however, I couldn’t help but notice the eye rolls and scoffs from those who were within earshot. Later they informed me that Alina, too, would be considered a Jabá (the feminine form of Jabao).

Families invested in ideas of social and racial mobility may even encourage children to find partners with lighter skin tones to “adelantar la raza” (literally translated as “improve the race”). These practices resonate with earlier policies of blanqueamiento, or biologically “whitening” the population, which gained pseudoscientific legitimacy in Cuba and elsewhere during the eugenics movement of the 20th century. These ideas led the Cuban government to encourage European immigration and heavily restrict non-White immigration in the early 1900s.

Today ideas of blanqueamiento get promoted informally through off-color remarks. If a family member dates someone with darker skin, for instance, a parent might say, “You don’t want children with bad hair, do you?!” Or, according to one of my interviewees, family members who have lighter skin than their siblings might be described as having “advanced more than the others.”

These offensive comments are not passive or harmless. They inform understandings of race, shape social interactions, and influence family decisions. Learned examples of anti-Blackness that get perpetuated in intimate settings help support longstanding and unjust systemic inequalities.

Though racial hierarchy remains entrenched in Cuba, some academics and activists on the island are pushing for change.

Within the last year, even before the most recent protests in July, Cuba has witnessed a string of small-scale demonstrations fighting for freedom of artistic expression and sometimes highlighting the disproportionate struggles faced by Afro-Cubans. In February, for example, the song “Patria y vida,” written and performed by Afro-Cuban artists on the island and abroad, became the latest anthem of resistance. Some have interpreted the song as a call for racial justice. [2] [2] The song “Patria y vida” (meaning “homeland and life”) became a rallying cry this summer when protests erupted in Cuba and throughout the Cuban diaspora.

In parallel, a relatively small group of academics have been actively calling on the state to formally address continued racial discrimination and allow Afro-Cuban history to be taught in schools. The activist group Comité ciudadanos por la integración racial (CIR; Citizens for Racial Integration Committee) has made similar calls. However, the state has responded by repeatedly detaining CIR members and attempting to discredit the organization.

My ethnographic work, echoing scholars of Latin America and elsewhere, suggests that those of us fighting for racial justice in Cuba should not forget to challenge more intimate settings as well. Anti-Black biases filter through family narratives and help maintain racial hierarchies across generations—contributing to the persistence of inequalities.

Looking more closely at how families talk about race can help dispel Cuba’s official narrative as a colorblind “racial democracy,” where all races are treated equally.