Anti-Asian Racism’s Deep Roots in the United States

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, incidents of harassment, discrimination, and violence against Asian Americans have increased dramatically in the United States. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, while overall hate crimes in 15 of the largest U.S. cities went down by 7 percent in 2020, those targeting Asian Americans went up by 149 percent.

The rising tide of anti-Asian racism—fueled in part by former President Donald Trump’s xenophobic response to the coronavirus—has prompted an outcry among Asian American communities, catalyzing activism and sparking nationwide protests led by the rallying cry “Stop Asian Hate.”

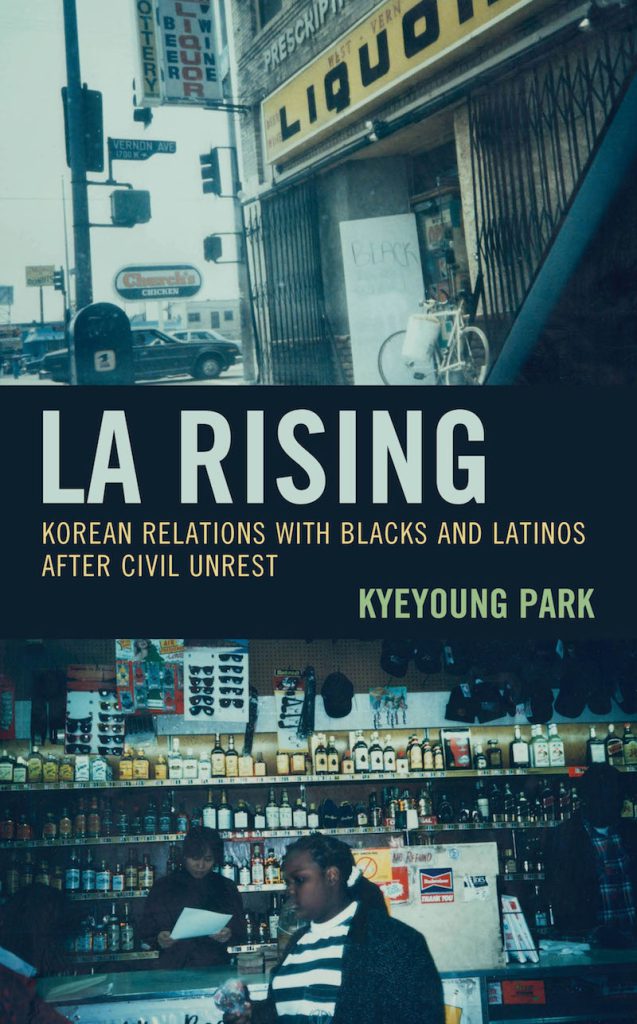

Kyeyoung Park, a professor of anthropology and Asian American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, studies migration, race/ethnicity, and inequality in the U.S. Her latest book, LA Rising: Korean Relations With Blacks and Latinos After Civil Unrest, focuses on the tensions that emerged between Black, Latinx, and Korean communities in South Los Angeles in the 1990s—a period of national reckoning with police violence and racism not unlike today.

SAPIENS editor Emily Sekine spoke with Park in April. This conversation has been edited for clarity, style, and brevity.

Some people still have trouble grasping that Asian Americans can be victims of racism at all, in part because of the model minority myth—the narrative that Asians have managed to succeed economically and educationally in the United States, especially in comparison to other minority groups. How does this myth contribute to anti-Asian racism in the U.S.?

Racism toward Asian Americans is often unacknowledged in mainstream media. I think it’s because the idea of White supremacy is based on a Black/White binary. Racism just doesn’t become part of the picture for some people if it is not directed at African Americans.

But other minorities have been racialized in different ways. Maybe economically, Asian Americans as a group are in a better position than other minorities, but politically, socially, and culturally, they are still seen as outsiders and are subject to Orientalist and nativist racism.

How does this kind of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia play out today?

For example, on March 29 in New York City, a 65-year-old Filipina woman was physically attacked in broad daylight. Her pelvis was fractured, and nobody helped her. And the guy who attacked her was saying, “You don’t belong here.” I think that’s very clearly nativist racism.

In the 19th century, Asians were seen as an economic threat, and right now that’s still the case. Since the Trump administration, but even under President Joe Biden’s administration, politicians and the media are always talking about China as a threat, an enemy. And ordinary citizens fear China. If you attack Chinese or other Asian Americans, some people think that is a patriotic thing.

On March 16, a 21-year-old White man named Robert Aaron Long shot and killed eight people—six of them Asian women—at Asian-owned spas in Atlanta, Georgia. These shootings have become a flashpoint for activists fighting anti-Asian racism, but some say these killings had nothing to do with race. Long himself said the murders were not racially motivated. Why is that problematic?

So many people—hundreds of comments on an article I was reading—were saying that they completely supported the claim that the shootings had nothing to do with race. And I thought, “Oh, my God.” Because talking to my fellow scholars in Asian American studies, it seems to be a commonsensical thing, that, of course, the shootings were race-based.

But outside of the Asian American community, like for many of these people, they would say it has nothing to do with race. They were thinking that it was about gender and sex addiction—like a mental health problem that the shooter could get treatment for—and that’s it.

We need to reject this kind of binary that says, “If it’s gender-based, then it has nothing to do with racism.” Historically, Asian American women have been racialized and sexualized and objectified. These women in Atlanta, they were targeted not just for their race and gender but also their work—service work—and their immigrant status: all of those things together.

What are the historic roots of anti-Asian racism in the United States?

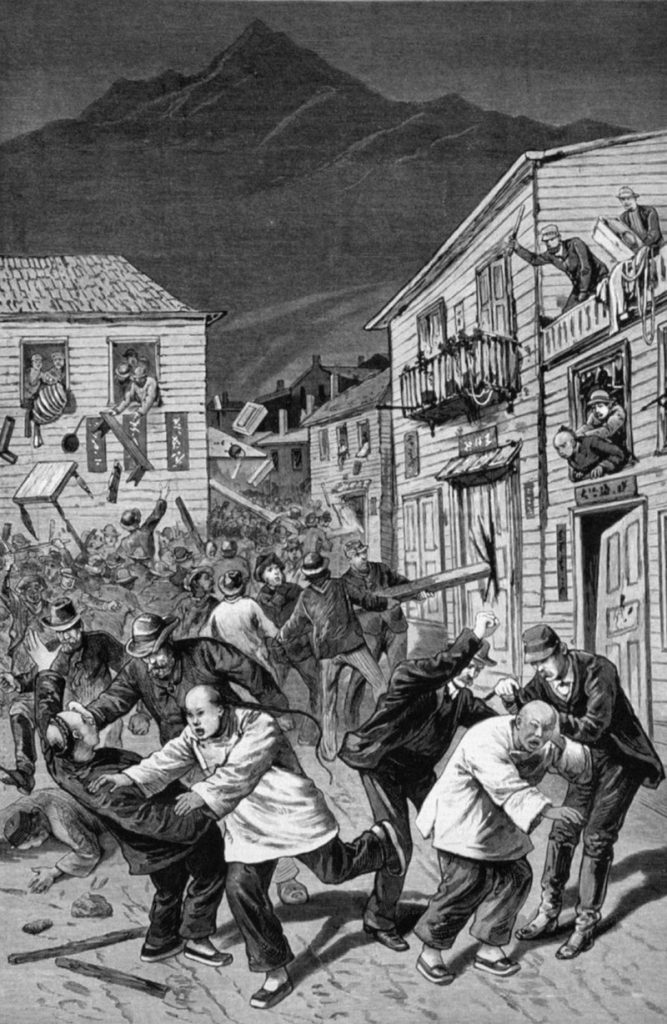

Since the 19th century, there’s been this sense of “yellow peril,” particularly when it comes to East Asians. People in the West thought that they would be invaded and that they would be kind of devoured—racially, even sexually. Chinese immigrants were really seen as unclean and uncivilized.

On October 24, 1871, there was a mass lynching in Chinatown in Los Angeles. At the time, there were only about 6,000 people in L.A. and around 200 Chinese immigrants.

The event initially started with a dispute among Chinese immigrants, and then somehow a White mob and White police officers tried to intervene. And then it led to attacking the Chinese. In the end about 10 percent of the Chinese population was killed. The people who had witnessed their fellow Chinese being killed were not allowed to testify because, following an 1854 legal decision, People v. Hall, Chinese people, like Native Americans and African Americans, were denied their civil rights to testify against White Americans.

Then, in 1882, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which denied citizenship rights to Chinese nationals already in the U.S. and stopped any further immigration from China. That was the first time the U.S. had ever banned immigration from another country—the first time that we said, “This group of people is not good enough to be U.S. citizens.”

Your work has focused on more recent conflicts, such as the civil unrest that emerged in the 1990s between Black, Latinx, and Korean communities in Los Angeles. This was after a jury acquitted four White police officers of beating Rodney King, a Black man, during an arrest. What was underlying those conflicts?

Six months before the Rodney King verdict was issued, a conflict had developed over the sentence given to a Korean grocer, Soon Ja Du, who killed Latasha Harlins, an African American teenager, over a shoplifting dispute. The Korean grocer was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter but given probation—no time behind bars. For African Americans, the sentence that was given to her was exactly the same as how the White police officers who beat Rodney King were given no prison time.

The mainstream media coverage of the Black-Korean unrest focused a lot on interracial conflicts, and I think this served to distract from the bigger issues of police violence and White supremacy in that particular issue. The media largely ignored the fact that these tensions also involved the White judge in the case who did the sentencing. They reduced Black-Korean tensions to simple “racial and cultural differences.”

But when I listened carefully to African American boycotters during my research, nobody ever had a problem with Korean American “culture.” They did talk about the lack of business ownership in their own community. So, you have to relate these conflicts to structural inequalities. There is so much anti-Black racism inside all of these public and political spheres—the criminal justice system, and also the media, financial institutions, and education system.

So, in that case, the tensions were rooted in African American communities seeing Korean immigrant communities benefiting from their proximity to Whiteness. Is that a rift that continues today?

Asians have benefited from White supremacy, not in the same way as White Americans, but to some extent. Asians have succeeded in part because they’ve been pitted against and complicit in anti-Black racism and racism against Native Americans. We have to reckon with that. And it’s also a fact that a lot of the hate crimes and racist incidents against Asian Americans today are committed not only by White Americans, but also by African Americans and Latinx people. We have to try to understand what’s happening there, without contributing to more policing or anti-Black bias.

This is really a question of a struggle for shared justice. We always have to remember that the U.S. is an imperialist empire, and the hate crimes we’re seeing today are a symptom of our racial capitalist and settler colonial society, which causes so much harm in and outside of the U.S.

A good sign is that a number of Latinx and African American politicians and activists are joining the Stop Asian Hate rallies, and Asian Americans are also joining Black Lives Matter protests. It can’t be an us versus them kind of thing.

That is the way forward—interracial, interethnic coalition building.

What would a real sense of belonging in the U.S. look like for Asian Americans?

Some people don’t understand that Asian immigrants couldn’t even become U.S. citizens until very recently. Policies barring or strictly limiting Asian immigration lasted for eight decades, until the Immigration Act of 1965 was passed. But I think in mainstream society, people interpreted it the other way around—that Asian immigrants were perpetual foreigners and never interested in assimilating themselves.

In my book, I develop this theory of a racial cartography to map out the complexities of inequalities that face different communities. Class and race are very important dimensions to understand inequality in the U.S., but they don’t explain everything. Neither does economics. Just because you make more money doesn’t mean you have a higher status in the U.S. Another key dimension is the politics of citizenship.

Just having legal papers, having your citizenship status, is still not enough for Asian Americans to belong in the U.S. I think Asian Americans have a long way to go in order to achieve full social and cultural belonging.