The New Old National Pastime

I attended my first spring training 50 years ago this month as a rookie in the Detroit Tigers organization. The 91-acre Tiger Town complex in Lakeland, Florida, had been a training center for pilots during World War II and home to squadrons of B-17s, B-24s, and P-51 Mustang fighters. Its air base heritage was evident in the two large hangars, which contained the first-ever indoor batting cages as well as an infield and pitching mounds for workouts on rainy days. Players ate in a military-style mess hall and slept in two-story wooden barracks that were painted forest green. Outdoors, four ball fields were arranged in cloverleaf fashion with a tower in the center to allow Detroit’s brass and coaches to watch multiple games and practices at once.

In March of this year, I returned to Tiger Town for a reunion of major and minor league Detroit Tigers from the 1960s and ’70s. About 100 former ballplayers attended, from Hall of Famers like Al Kaline to guys like me who played a few years in the minors. The reunion coincided with the 2016 spring training, mixing past and present. As an anthropologist who studies baseball culture, I saw this visit as a rare chance to understand how spring training has changed over the last half-century.

Enough of the old Tiger Town complex remains to trigger many memories. The two large airplane hangars are still standing, although they are now only used for storage, and Tiger Town’s four diamonds are still laid out in cloverleaf fashion. But a lot has changed too, and I couldn’t help noticing how different today’s spring-training experience seemed. I wondered what the current crop of players were like, so I put on my anthropologist’s cap and fell into fieldwork mode.

The most obvious difference in the spring-training environment were the facilities. The old wooden barracks where I had bunked with my teammates on Army cots, four to a doorless room, were gone, replaced by a modern, air-conditioned cinder-block structure similar to a college dormitory.

Also missing was the morning reveille—Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass piped through the PA system—followed by a brief motivational announcement: “Good morning, Tigers! It’s going to be a beautiful 76 degrees in Lakeland today. It’s just 22 in Detroit.” We used to file into the mess hall en masse for scrambled eggs, bacon, sausage, French toast, and pancakes. Despite being in citrus country, the orange juice was from concentrate, and the fruit was canned. It was rumored the Tigers put saltpeter in our food to reduce our sexual appetites. Today’s players wake up on their own schedules and go to the cafeteria for a similar type of breakfast.

I asked the dormitory supervisor for a copy of the house rules. These haven’t changed much from a half-century ago, when they were posted on the bulletin board. For instance: “Lights out at midnight.” In my day there was little enforcement other than an occasional bed check. Today security cameras record anyone coming in late.

In our day, the fields were patchy and uneven and there were no outfield fences.

Here’s one that’s new: Players must register their “personal TV, stereo, and game system, etc., at the front desk.” I learned that, because of such devices, today’s players seldom leave the dorm in the evening. In the pre-internet, pre-electronic game era, we often went into downtown Lakeland or to nearby Florida Southern College at night looking for things to do, particularly hoping to meet local girls. Today’s players talk to their girlfriends and their families daily by cell phone and regularly use social media.

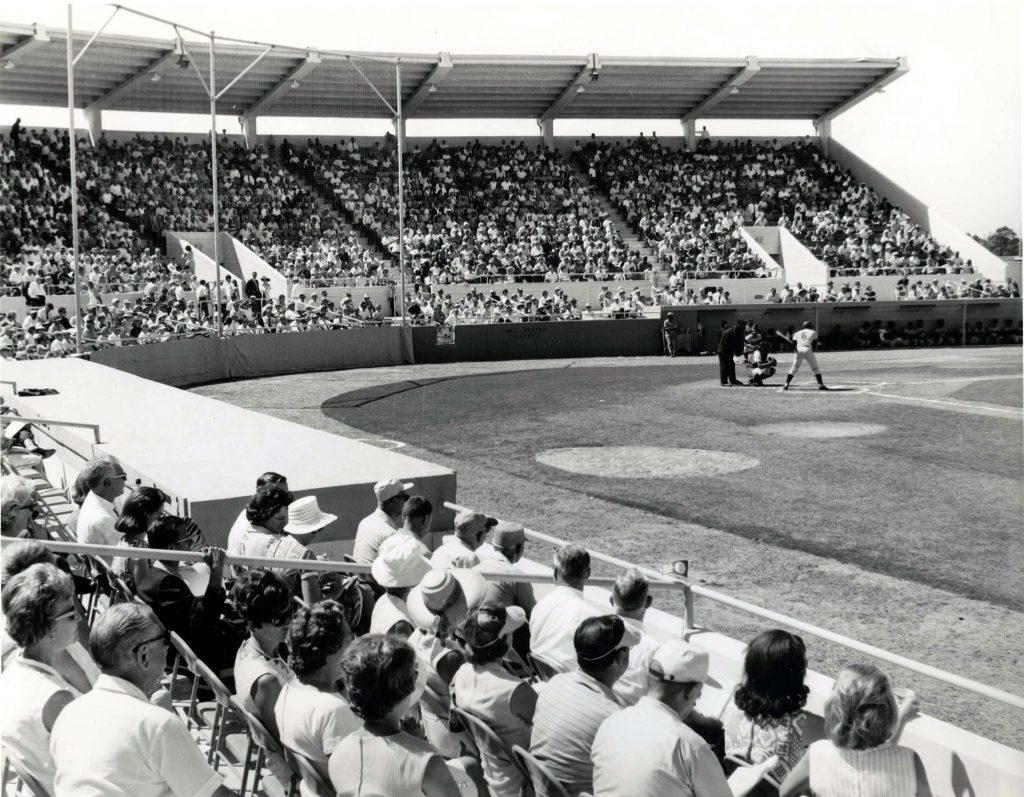

With several former teammates, I visited the ball fields where we’d all done our best to impress our coaches and make a roster. We recalled sneaking looks at the center tower, hoping that the brass had seen an outstanding play or praying that they had missed an ignominious error. The playing fields were as well-groomed as any big-league infield; even the outfield grass was immaculate. In our day, the fields were patchy and uneven and there were no outfield fences. A simple ditch ran around the field’s perimeter, and beyond that was Lake Parker, with resident alligators.

Familiar names dotted the facilities—mostly famous players, of course. But the Popovich Clubhouse was named after the clubhouse attendant from my day, George Popovich, who issued me my first uniform. On my first day in camp, he handed me a bottle of sunscreen, warning me about the Florida sun and advising me to slather up, including the tops of my ears.

Baseball today is loaded with technology and equipment that did not exist in the 1960s: radar guns to clock pitchers’ throwing speed and video cameras to record hitting and pitching mechanics. When I played, batting gloves were nonexistent and our batting helmets did not offer ear protection. Baseballs were made of horsehide, not the smoother cowhide as they are today (and have been since 1974 because of a shortage of horses). We wore heavy wool hand-me-down uniforms. Today’s players wear a lighter, moisture-resistant fabric that boasts a 4-way stretch.

Only the baseball bat has remained the same. A few players let me swing theirs; they were more or less the same length at 34 inches and about the same weight, 32 ounces, as the ones I used in my career, although the handles were thinner.

As I mingled with players around the batting facility and the cafeteria, I couldn’t help but notice that today’s players are bigger and stronger. At 6’2” I was taller than most of my teammates; today I would be average at best, and shorter than most pitchers. The strength and speed I witnessed far surpassed what I knew in the 1960s. Today’s players are lifting weights and working out year-round, many with personal trainers. Spring training was traditionally a time and place for players to get their bodies in shape for the coming season. Today’s players arrive in camp already in shape. Most hitters are primed to go in a few weeks; the pitchers still need the additional time to reach season readiness.

I heard almost as much Spanish as English in Tiger Town. More than 45 percent of all minor league players, and about 30 percent of major leaguers, are Latinos. Fifty years ago, that number, for all spring-training camp players, was not quite 10 percent; the influx of ballplayers from the Caribbean and Latin America had only just begun.

The Latino players influence more than language. They tend to play with a looser, more passionate—some say flamboyant—style, one that’s acknowledged by Latinos and Anglos alike. I noticed more joking, horseplay, laughter, and, well, flair than I remember from my day. I observed behavior that we would have called “hot-dogging”—celebrating a home run with a fist pump or a flip of the bat—which we would have responded to with a knockdown pitch the next time the offender came to the plate.

The number of Latino players and coaches has reached a critical mass where their style of play has become an accepted part of the game. The fans of this generation certainly like it, and so do I. It has enlivened the game.

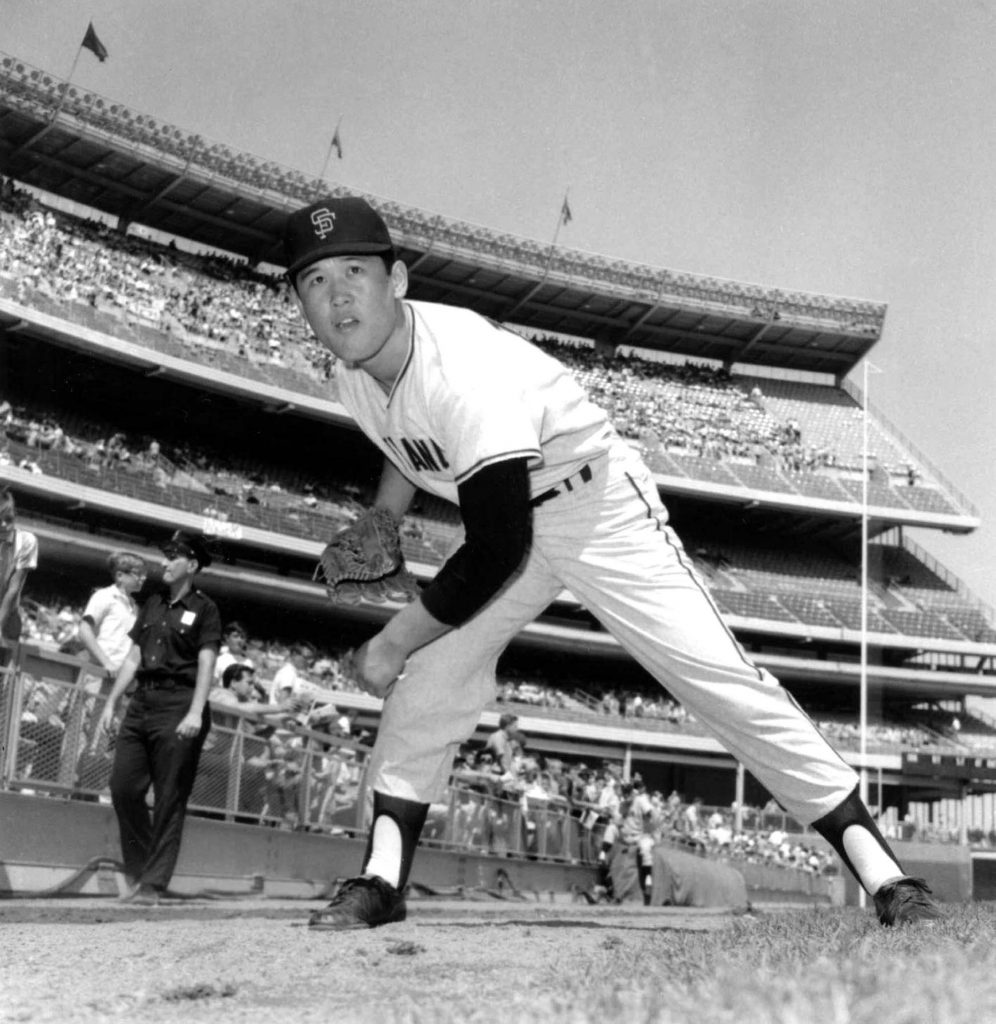

In the 1960s, baseball had only one Asian-born player—Masanori Murakami of the San Francisco Giants. In 2015, there were 13 Asian-born players in Major League Baseball. In contrast, the number of African-Americans in baseball has dropped from 13 percent in 1966 to 8 percent today. (Their all-time high in the big leagues was 25 percent in 1974.)

Of all the changes, the most shocking to me were ballplayers’ salaries—not how much major league players make today but how little minor league players receive. The pay structure of modern-day baseball may be the most glaring example of income inequality in the American workplace.

First-year players typically sign contracts for $1,200 per month for the upcoming season—about $6,000 a year. And like all professional ballplayers, they earn nothing during their six weeks of spring training. Playing seven days a week—an average work week during the season is 63 hours, not counting travel—minor league ballplayers earn $4–5 an hour, well below fast food workers’ median hourly wage of $7.

In 1966, the starting salary for rookies was $500 per month—or $3,675 per month in today’s inflation-adjusted dollars. That means that entry-level salaries for minor leaguers have declined by two-thirds. If you knew nothing about professional baseball, you’d think that the sport had fallen on hard times. Far from it. The value of major league franchises has gone through the roof, and the average salary paid to major league ballplayers, adjusted for inflation, has increased by a factor of 250—from $17,664 for a season in 1966 to $4.4 million today. Big-league stars like the Tigers’ Miguel Cabrera and the Los Angeles Angels’ Albert Pujols make around $140,000 per game, which is not that much less than the entire 25-man roster of a low Class A team over an entire season—or $162,500.

The young players I spoke with at Tiger Town acknowledged being grossly underpaid and feeling taken advantage of. They were aware of the class-action lawsuit filed in 2014 by a group of former minor leaguers against Major League Baseball, challenging the below minimum wage salaries as well as the lack of pay during spring training. Indeed, players were invited to join the lawsuit, but those I spoke with declined because they feared it would hurt their careers. I heard another justification from several players and coaches, practically word for word: “Not making much money can make you play harder and get you to the big leagues quicker.” Our reward will come, the players said, when we make it to the big leagues. I mentioned that only 5 percent of rookies in their position ever make it to the big leagues, and they did not disagree.

In the Tiger Town cafeteria, I joined a trio of current players for lunch. All three were attending spring training for the first time, and all had been drafted out of college. This is true for most of today’s players and is quite unlike my 1966 cohort, of which few players had been to college. (However, as of 2012 only 4 percent of today’s major leaguers have completed a four-year college degree.)

During lunch I admired the cafeteria’s homage to Tiger history. Jerseys of former Tiger stars adorned the walls, and baseball cards were laminated onto the tabletops. I pointed out the cards of some of my former teammates and told my young lunch mates that it was exactly 50 years ago that I had come to my first spring training. They were polite and willing to answer my questions, but none of them showed any interest in what spring training or minor league ball had been like a half-century ago. When I asked directly if there was anything they wanted to know about what it was like back then, one player, a pitcher, rather lamely asked, “Well, what was the pitching like?”

I was surprised by their lack of curiosity. I fondly remember listening to my coaches tell stories about the old days. Most of my teammates also enjoyed these bull sessions. Later, I asked Dave Littlefield, vice president of player development for the Tigers, how much interest today’s players had in baseball history. “Not much,” he said, and he mentioned media reports that found some of today’s major leaguers did not know influential figures like Curt Flood (whose refusal to be traded led to the era of free agency and the high salaries that major leaguers enjoy today).

Much of the pleasure of reconnecting with my former teammates came from storytelling. Baseball has a rich narrative tradition, in part because the games are played every day and are not on the clock. There is a great deal of downtime at spring training and during the regular season—time that gets filled with banter and antics. Many stories have been finely honed over the years through many retellings, and some have grown to mythic proportions.

I felt a deep connection to my fellow players, deeper than anything I’d experienced at a school reunion. Our first seasons together created strong bonds. In a difficult environment, we depended upon each other for companionship and support. As rookies, most of us had never lived away from home, and we had to adjust not only to new places and the pressure to succeed—to put up good numbers—but also to the absence of families and girlfriends.

Thrown together with others in the same situation, I relied on my peers for comfort and commiseration and formed lifelong bonds in the process. I wondered if today’s players, who are always connected to family and friends at home through electronic means, and who spend much of their free time alone with their personal electronics, were less dependent upon their teammates. Will they develop bonds as close as my generation?