A Japanese Sea Spirit Battles COVID-19

This spring, in western Tokyo, my research assistant Payton Letko came upon an unusual treat in a small bakery: pastries in the shape of the Japanese folklore creature Amabie, a three-legged sea creature with scales and long flowing hair, who is said to appear on land from time to time to bring news of a bountiful harvest or warn of a coming pandemic.

The pastries are just one example of numerous depictions of Amabie that have popped up throughout Japan in 2020 in everything from stickers to animation. Even the long-eared futuristic creatures that serve as the mascots for the Tokyo Olympics (planned for the summer of 2020 but delayed until 2021) have been spotted wearing Amabie costumes in a kind of double-cosplay.

The reason, of course, is that Japan, along with the rest of the world, is facing the difficult challenge of containing the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The bakery’s proprietress, an obaachan (grandmother) who prefers I not use her name in this piece, explained that Amabie has resonated so suddenly with the Japanese people because they “want to cling to anything, just like praying to gods for help … it is just Japanese culture.”

As the legend goes, she recounted, this powerful mermaid appeared, urging that “when a plague breaks out, copy my figure and hand it out to everybody.” The obaachan continued: “Then, the [creature] went back to the sea. The story ends after this, and the plagues disappeared.”

Amabie is a member of the yōkai: a vast menagerie of folkloric spirits, monsters, and tricksters, often embodied as animals, who are variously mischievous or benevolent. Japanese people recognized these supernatural figures at least as early as the eighth century, but it was during the middle to late Edo period, in the 19th century, that yōkai assumed a mass popularity, often featured in ukiyo-e (woodblock prints).

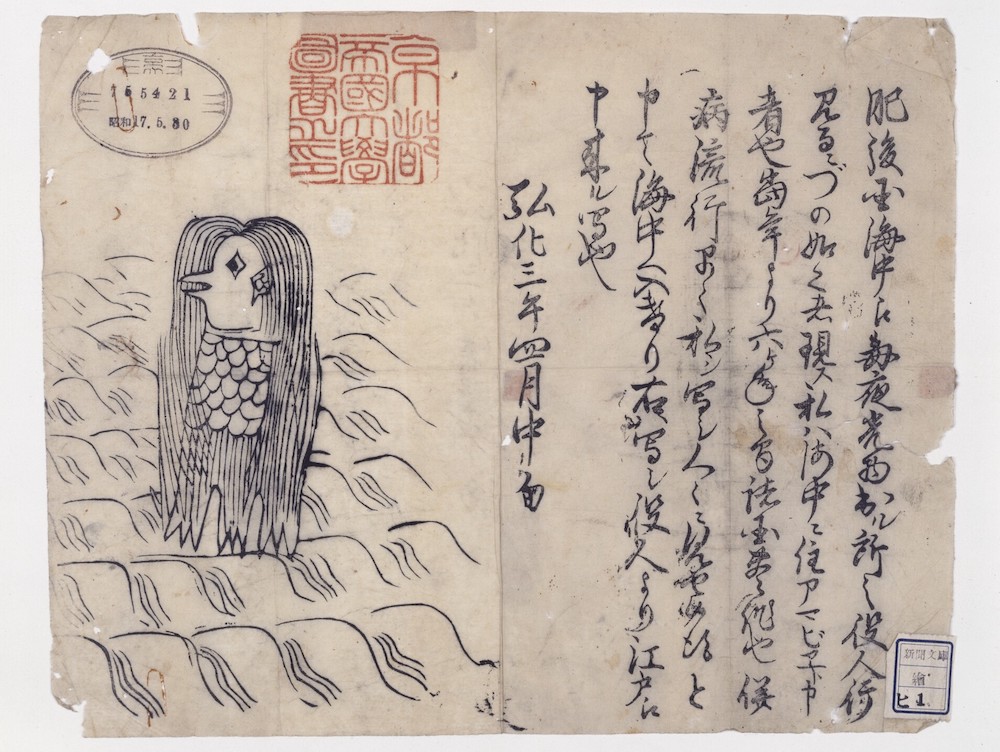

Perhaps the oldest image of Amabie is from one of these woodblock prints from about 1850. According to the text in that print, Amabie first appeared in May 1846 in what is today Kumamoto prefecture on Kyushu, Japan’s southern island. Japanese society had begun to open up significantly to the outside world at this time, which happened to coincide with a number of cholera plagues.

People saw a glowing light in the sea for several nights, and a town official who went to the beach was the first to meet the three-legged yōkai. Amabie announced its image should be shared with sufferers of plague so that they and their communities would be cured—almost exactly the version of the story conveyed by the baker.

Curiously, Amabie did not seem to play a role during the 1918 flu pandemic. Instead, Japanese society focused on much older yōkai creatures dating to the late eighth century called yakubyougami—supernatural demons or pestilence spirits thought to infect people with illnesses. Images of yakubyougami appeared in public service posters, including one in which a yakubyougami sits upon the shoulder of a sick mother to fan her coughed flu pathogens across the table and into the faces of her children. Public information offering guidance for protection from the flu emphasized the wearing of masks and social distancing.

Today Iwate prefecture—a rural region in northern Honshu—is well-known for hosting an especially rich population of yōkai in its forests and rivers. A 40-something civil servant from this region, who wished to remain anonymous, discussed the significance of Amabie with me. “Japanese people, for the most part, don’t really believe in yōkai like Amabie,” he said. “The purpose of all these Amabie images seems to be, in my opinion, to bring Japanese people together, to lift our spirits, and to motivate us to work against the virus.”

In my own experience, the majority of Japanese folks claim to be nonreligious nonbelievers, even though everyday life in Japan is replete with shrines, temples, and religious festivals. Indeed, there seems to have been a trend, noted by Western and Japanese observers, of decreasing religiosity among Japanese people since WWII.

Religion scholar Satoko Fujiwara’s analysis of this trend matches with what the civil servant told us: Fujiwara asserts that nonreligiousness in Japan is better understood as “religion as human relationships,” or a sort of “practicing belonging.” The spiritual practices of contemporary Japanese often involve seeking and purchasing various amulets or other items that become most meaningful among intimate networks of friends, rather than among the wider public.

As an anthropologist in Japan who focuses on popular culture, I can see that iconic demons and gods reckoned as playful, dualistic figures on personal commodities (including pastries) create ways for individuals to ritually connect to public problems and society’s anxieties. Amabie has emerged as a highly desired character and a symbol of a shared commitment to anti-pandemic measures.

This form of meaning-making is hardly unique to Japanese society. Indeed, Amabie has become transnational. Her image is now commonplace on social media throughout the world (#amabie), and drawing contests have taken place in many countries, including Canada, South Korea, and Europe, as young and old try their hand at fashioning colorful versions of Amabie. Fascination with this pandemic-fighting mermaid transcends Japan, as people everywhere respond in creative ways to COVID-19.