When Gaming the System Is the Only Way to Parenthood

Sonsoles and her partner had set their hearts on adopting a child. [1] [1] All names in this piece, except for the authors’, are pseudonyms and are used to protect the identities of those who were interviewed. They lived in a nice Barcelona neighborhood, and from the start, Sonsoles explained, she was sure they would be approved to adopt. They were a kind, loving couple who would be devoted to their child. And though she might not have had the figures at hand, the vast majority of applicants are approved to adopt in Spain—97.4 percent in 2016—so she had little reason to fear being turned down. Much to Sonsoles’ shock, however, their application was rejected on the grounds that their house wasn’t suitable for a child.

The unexpected rejection threw Sonsoles into a kind of game that those applying for adoption are often forced to play: one of staging their houses and their lives to fit a set of perceived unwritten rules about who makes a good adoptive parent. Sonsoles, like others, played this game on the basis of hearsay and guesswork because there was nothing else available. It is a game that seems to put unfair stress and pressure on prospective parents, and in some cases, it appears to place them in a horrible moral dilemma.

The reason the authorities gave for denying Sonsoles and her partner was logistical: Their would-be child’s bedroom was located on the ground floor, while their bedroom was on the upper floor, and the two floors were connected by a staircase in an interior patio. Sonsoles thought this layout wasn’t ideal for an infant and had figured she would simply put a crib in the corner of the master suite or its adjacent workspace. But she felt she couldn’t say all of this explicitly because she believed there to be an unwritten rule against having a baby sleep in the same room. On top of all of this, Sonsoles suspected that their application was actually denied because of her colorfully dyed hair and her unconventional attitudes toward parenting and marriage: She was not committed to trying to have a biological child with her live-in partner, for example, which she felt the evaluator deemed odd.

To her, and others we’ve worked with in our social anthropology research, the home study seemed to reflect projections by state authorities as to what a family should look and act like, often reproducing middle-class values, more traditional gender norms, and antiquated moral codes.

Yet, are these unwritten rules really rules, or are they mistaken assumptions on the part of the parents? Would it be better if authorities made their expectations around “house” and “family” clearer—but also more flexible? Or does leaving a little wiggle room in the evaluation allow necessary space for what some officials say are “common-sense” judgments regarding their assessments of prospective parents? There are no clear answers to these questions, which leaves prospective parents caught in an inefficient and sometimes heartbreaking system of guessing games as they try to predict what authorities seek.

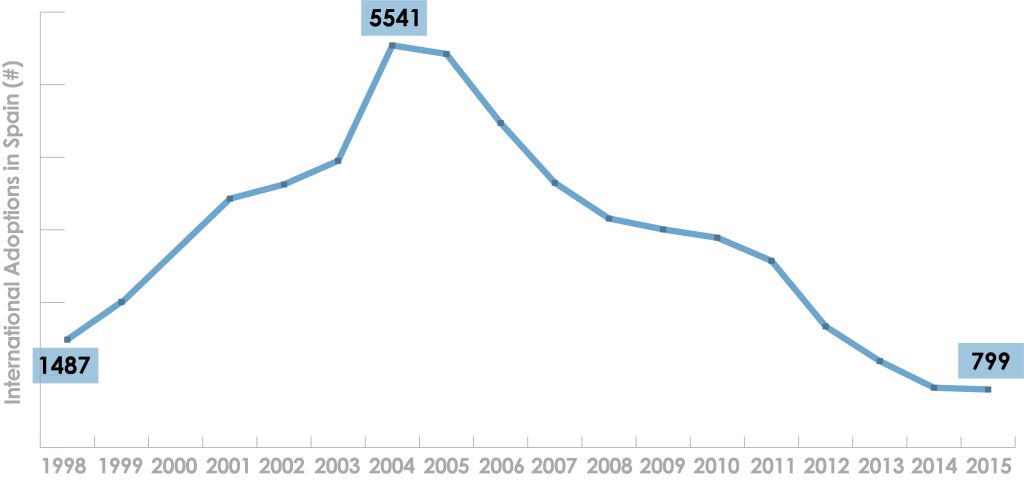

In the first decade of the 21st century, Spain had one of the highest adoption rates in the world. In the peak adoption year of 2004 in Spain, 12.4 international adoptions took place for every 1,000 live births, compared to 5.54 per 1,000 in the United States that same year.

Given this high rate of adoption success, flaws in the system became readily apparent. Most applicants are approved in Spain—but the system lets in some adoptive parents who later end up handing their children over to state custody. Little reliable data on failed adoptions exists for Spain. But extensive research by psychologist Ana Berástegui in Madrid in the early 2000s and an analysis by Catalan child welfare officials in 2016, reported in the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia, together suggest that 1.5 percent of adoptions fail. The rate increases to 6 percent in cases where the children are older than 6 years of age at the time of placement, which is increasingly more common as the demographics of adoptable and adopted children are changing. (For example, drawing from U.S. figures, 16.5 percent of internationally adopted children in 2007 were aged 5 or older, and by 2014 that figure had reached 39 percent.) These adoption failure rates are similar to (or in some cases even lower than) those in other wealthy countries, but of course, each instance represents a tremendous upheaval in the life of a child and their family.

When we set out as anthropologists to study adoption in Spain in the 2000s, along with our colleague, linguistic anthropologist Susan Frekko, we found applicants struggling to understand the system. They knew, for example, that they were required to provide photos of the home where the child would live, but they didn’t know what made for a “good” house, in the same way that no one ever spelled out what was meant by the all-encompassing phrase “the best interests of the child.” So they took guidance from online forums and adoptive parents about what really “mattered” to social workers. Many of those stories threw a spotlight on their house as the ultimate criterion—in particular, whether it had “suitable” sleeping arrangements for the child.

A “suitable” room for a child is relatively straightforward to measure—easier than, say, empathy or patience—and its absence easy to give as a reason for denial. But clearly it is not the best or only criterion for good parenting. However, according to social scientists who study adoption, the implication that a child should have a room of their own is widespread in the adoption process around the Western world.

A 2017 study on how children’s sleeping arrangements impacted their sleep concluded that infants 4 months or older who share a room with their parents—the recommended practice up to age 1, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics—are more likely to have “less nighttime sleep in both the short and long term, reduced sleep consolidation, and unsafe sleep practices previously associated with sleep-related death.” (In the first months, co-sleeping in the same room, but not in the same bed, is usually recommended to help prevent sudden infant death syndrome.) The research results showed that if parents and young children share a sleeping space, then the children are four times more likely to be brought into the parental bed, something strongly advised against by mainstream pediatricians. When that study was picked up by media around the globe, including in Spain, it struck a nerve with parents anxious to protect their children.

But concerns about co-sleeping are not new: They have 19th-century origins in historical notions of decency and propriety. For example, Spain’s approach to child welfare draws on 19th- and 20th-century French child welfare laws that emphasized parental morality. Debates about sleep at that time were concerned with preserving the privacy of marital intimacy to protect both the national fertility rate and the child’s modesty.

And nowadays, in nations where blood relations are thought to define kinship, we wonder whether adoptive family co-sleeping raises additional anxieties. Such worries seem to have led to an idealized, “Goldilocks-style” view of where a young adopted child should sleep: neither too close nor too far away. The child should be in their own room for privacy but close enough to allow parents to monitor or discipline them and provide a sense of security.

This is a fine ideal in principle, but it does not always match up with reality. Not all prospective parents happen to live in a home with the “right” kind of sleeping arrangements; no one would expect a young child who is biologically related to his or her parents to be removed from a home solely for having the “wrong” kind of sleeping arrangements. Besides, anthropologists have shown that co-sleeping or room sharing with small children is widespread around the world and associated with many positive outcomes, such as increased breastfeeding, a well-functioning nervous system, and a sense of “social-psychological connectedness” that provides the foundation for later independence. And in many places in the developed world, including Spain, co-sleeping is—if not the prescribed practice—certainly recognized as a common and comfortable arrangement for getting everyone to sleep.

Yet the false ideal seems to persist among adoption officials. The existence of a “Goldilocks” room may serve some useful purposes for them: It speaks to an applicant’s financial well-being and implies that the prospective parent subscribes to a certain set of middle-class values about family life. But, clearly, it does not equate to being a good parent. And ironically, while some applicants are rejected for having a second bedroom on a different level than the master bedroom—others aren’t. The house seems to be a resource that social workers can draw on to justify approval or denial in the absence of explicit rules. In other words, because the exact characteristics of a “Goldilocks” room are not universal, other undisclosed factors also appear to be at play in the home evaluation.

These unfair criteria—or at least people’s perceptions of them—have real effects on how families prepare for adoption evaluations. For instance, one couple, Clara and David, prior to submitting their adoption application, knew they would need to expand their one-bedroom Barcelona apartment. In this densely populated and historic city, many apartments are just 700 square feet and expanding them requires significant work and many permits. They paid for an architect to draw up plans for two additional bedrooms, but they were unsuccessful in getting a city permit to build the extension. So, instead, they rented out their apartment so they could lease a larger one nearby. Their new rental had two bedrooms, but still they worried it might be seen as unsuitable because the master bedroom was upstairs and the child’s bedroom was downstairs. In the end, they passed the housing inspection easily. The social worker “saw that … she [the child] had a room,” David explained. “She didn’t look at anything else.”

As was the case for Sonsoles, other perceived unwritten rules governing adoption likewise force applicants to play a game of staging their lives for inspection. Some tell the authorities that they have given up trying to have a biological child, for example, when in fact they are still trying, because that’s what you’re “supposed to say” when adopting. Some try to erase signs of a same-sex partner, as many “sending countries” for international adoptions do not consider gay partners to be a suitable parenting arrangement. Nuria, for example, emptied her entryway of coats that weren’t her size or her style, rearranged the living room furniture, and removed all of her partner’s books, music, and toiletries from the premises to hide away the existence of the woman who would become the child’s other mother and, later, Nuria’s wife.

Sonsoles eventually took out a loan to purchase a new flat that better matched her understanding of unwritten rules about bedrooms for adoptive families. Though she never actually moved into it, she placed boxes and bags from Ikea throughout the new apartment and met the social worker there to illustrate her acceptance of the idea that the house mattered. She also removed the bright color from her hair and made it clear to the social worker—in an effort to avoid any disapprobation about her male partner—that she was adopting as a single mother. Her second application was successful. Though the extent of this subterfuge might make some uncomfortable, we would argue that both Nuria’s and Sonsoles’ efforts spoke more of their desperation, and of how they perceived the system to be unfair, than of flaws in their moral character and suitability for parenting.

Adoption is a complicated process, and additional pressures are increasing as the numbers of international adoptions continue to fall. The “supply” of available children for international adoption has fallen dramatically, largely because of policy changes in once-dominant “sending” countries like China and Russia. As waiting lists grow—because no subsequent decrease in “demand” has occurred—some prospective parents face the fact that no matter how much time, money, and worry they invest, they may never adopt a child.

Determining the best way to predict who will make an adequate parent is a challenge beyond our ability as anthropologists to solve. We can say that the fact prospective parents feel they have to stage their houses and lives seems counter-productive to placing children into loving homes. It is unfortunate that potentially good parents spend valuable resources obsessing about their houses to an undue degree, that some prospective parents end up lying about their lives, and that deficiencies in the house are seemingly used as excuses to mask other, less palatable reasons for an applicant’s denial.