How Water Insecurity Impacts Women’s Health

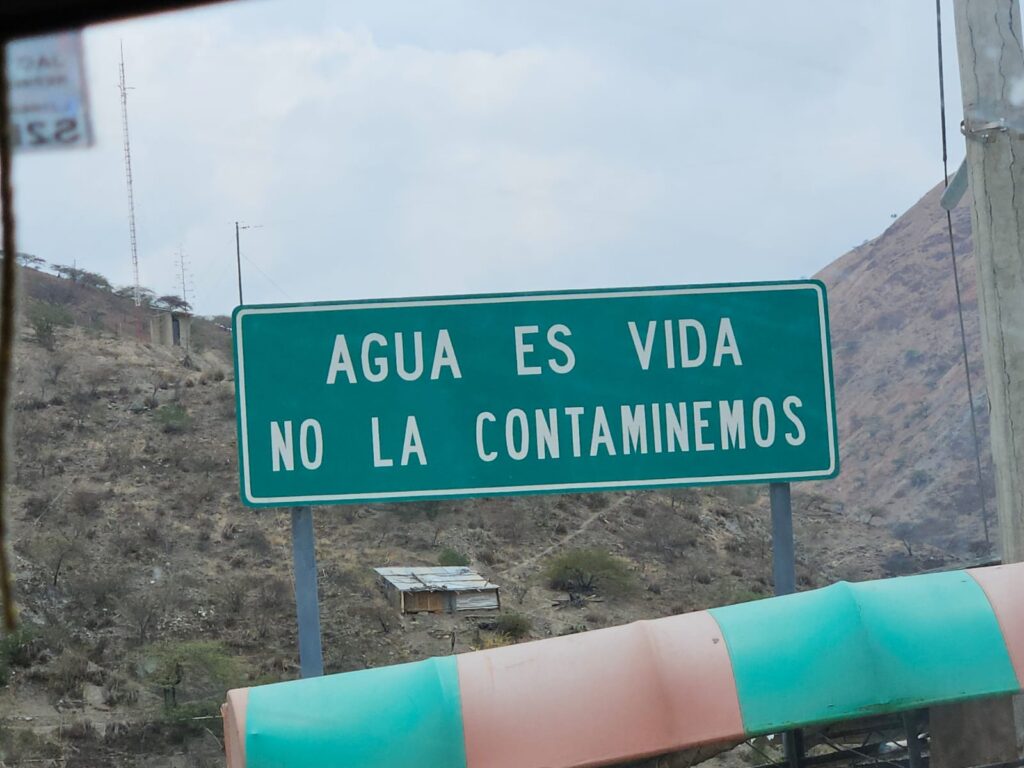

In the northern desert of Peru, a tin roof shades women from the beating sun as they wait for rusty water tanker trucks that are often delayed. The trucks will dump water into algae-lined cement reservoirs, from which the women will fill their plastic jugs.

This water station, organized by the local authorities and community members, is appreciated by locals. But it is not sufficient. Each week, the station provides 120 liters of water to each family. The United Nations recommends each individual receives, at a minimum, 700 liters of water per week.

To compensate, many women buy expensive water from private water trucks or walk 40 minutes to the river, hauling babies and toddlers on their backs. The women say the river water is cochino, or dirty like a pig. Their community lies downstream from a larger town that dumps its sewage into the river and from mining operations that release mercury and other toxins into the waterways.

The women know the river water can sicken their families, but they need it to survive. They must carry containers of the river water—and their children—back home. The weight of the water is enormous, physically and emotionally.

Worldwide, water insecurity—the inability to access and benefit from affordable, adequate, reliable, and safe water—is increasing at an alarming rate. Today an estimated 27 percent of the global population lives in severely water-scarce areas. Scientists predict that by 2050, more than half of the global population will live in areas that suffer from water scarcity for at least a month each year. As this happens, more people will encounter a confluence of water-related challenges, including substantial disease risks, constrained economic opportunities, and political instability.

While a water-insecure world affects all people, women and children often suffer the most. Our international team of academics and activists has witnessed firsthand how water insecurity impacts women’s health on opposite sides of the globe. Working in Indonesia and Peru, we also use this research, and our close partnerships with local communities and organizations, to spur action that supports gender equality and the basic human right to water.

WATER INSECURITY AND GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE

The statistics on rising water insecurity are distressing. An estimated “1.8 billion people drink unsafe water” and some “2.4 billion people live in water-stressed countries.” The connection between poor water quality and serious threats to health, such as gastrointestinal infections and diarrhea, are well-documented.

Less discussed is the connection between water insecurity and violence against women. The United Nations defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women.”

In 2015, while conducting anthropological fieldwork in eastern Indonesia, a member of our team (Cole) heard local women discussing how water shortages were triggering arguments between partners. Too often these arguments turned violent, with men slapping, pushing, or otherwise beating their wives.

Cole suspected these experiences might represent a more widespread link between water insecurity and gender-based violence. Over the next few years, she partnered with the rest of us, researchers focused on household water insecurity, epidemiology, and social work. In 2020, we launched a first-of-its-kind study about what happens to women’s health and well-being when water sources run dry—starting in Peru and Indonesia.

INVESTIGATIONS IN PERU AND INDONESIA

Though about 11,000 miles apart, the northern coast of Peru and the small island of Sumba, Indonesia, share commonalities. Like the desert region of this part of Peru, Sumba is arid with extremely limited fresh water. The Jakarta Post reported that Sumba went 249 days without rain in 2019. Peru’s northern coast regularly suffers droughts followed by torrential rains, some so severe the Peruvian government has declared states of emergency multiple times over the past few years.

To learn how water issues impact women, we ran interviews and focus groups with community members in Sumba, Indonesia, and in Tambogrande, Peru (a Peruvian district with just over 100,000 residents). The results shocked us.

Study participants recounted the physical strain of carrying heavy water buckets from collection points to their homes. The exertion led multiple women to go into premature labor and even miscarry. An Indonesian woman told us, “I still had to draw water until it was time to give birth. I fell near the spring, and I was taken to the hospital and gave birth to my child not being full term.” In Peru, a woman explained, “I had to go with my buckets for the water after giving birth, and a few days [later], I felt something between my legs that fell.” Her uterus had prolapsed (slipped) into the vaginal canal.

In Indonesia, women struggled to secure water for sanitary births. During the birthing process, clean water helps prevent infections.

And in both countries, when water scarcity prevented women from completing household tasks, such as making coffee, they experienced violence from their partners and other family members.

Putting some numbers behind these personal testimonies, 365 women completed our surveys in Indonesia, which included validated measures of household water insecurity and gender-based violence. Our analyses revealed that Indonesian women in water insecure households were more than twice as likely to report experiencing gender-based violence in the last year.

Yet women in Peru did not report experiencing gender-based violence in our study. This contrasts with local statistics that document high rates of violence against women in the broader region. The discrepancy between our study and known rates drew our attention to cultural barriers to reporting violence—and the need to consider how cultural norms impact women’s lives.

RESEARCH FOR CHANGE

To ensure our findings became useful for local stakeholders, we transformed the data into talking points for in-person workshops with study participants. For government authorities, we created policy briefs, translated into Bahasa Indonesian and Spanish. And critically, we partnered with local women activists who promote education and social change to address water insecurity.

In Sumba, our key community-based partner is Martha Hebi, a woman with a bright smile who exudes enthusiasm and tenacity. With a long history of working with local women, villagers, and leaders, Martha runs a grassroots solidarity group for women and children called Komunitas Solidaritas Perempuan dan Anak (SOPAN).

After participating in our research project, Martha realized that water bridges people. “When we talk about water, we talk about basic needs for everyone,” she said.

But Martha also observed that water scarcity more severely afflicts women and people in the lowest caste, who are effectively enslaved in Sumba. Under a shady tree near a spring that gives less water every year, Martha explained, “Every household member is affected by the lack of water, but it is women, especially female slaves, who share the greatest burden.”

With Martha and her team at SOPAN, we designed curricula for high school students and health care workers to explore relationships between water and women’s health. The training integrated local imagery, such as the mamuli, a traditional symbol that resembles a uterus or vagina and often adorns Indonesian jewelry or fabric. The mamuli helped spur discussions about how a lack of water can prevent menstruating people from staying clean during their periods.

“Because a mamuli is considered a sacred symbol for the Sumbanese,” said Martha, “we use this to remind people that women’s reproductive health needs to be taken care of properly, which includes having enough clean water for hygiene.”

Menstrual hygiene and gendered labor differences often prevent young women and girls from attending school—contributing to a gendered cycle of truancy and poverty.

Other pictures in the curricula familiarized community members with situations usually considered taboo: A man collects water, a father cooks while a mother breastfeeds their baby, and both men and women participate in village meetings about the maintenance of water springs.

In Peru, we work closely with Marleny Bardales Raymundo. Referred to as hermana, “sister,” by her peers. Marleny directs a rural educational network for Fe y Alegría, a Jesuit nongovernmental organization that works in Tambogrande.

Educators for Fe y Alegría have noted that many girls often drop out of school before graduation—and water scarcity in one of the factors that underlies this gendered attrition. “We managed to get everyone to go to school, boys and girls,” said Marleny. But for girls, “you go to school, but first you have to leave the water; you have to get breakfast ready. You come home from school, and … you have to wash your father’s and your brothers’ clothes while the boys are playing soccer outside.” Girls are first to miss out on school or any other activity if water provision becomes a problem.

Similarly to working with SOPAN in Indonesia, we are collaborating with Fe y Alegría to incorporate gender equality and environmental education into the curricula for rural schools. In Peru, our newly developed workshops train local schoolteachers and students to talk about the ways gender roles and machismo (toxic hypermasculinity) can lead to water-related tasks being “women’s work.”

GROWING A GLOBAL SISTERHOOD

It seems our work has seeded change.

On a return trip to Indonesia, village leaders told us that their involvement in the research project led them to elect the first woman to their government council and to hire a village midwife. In a neighboring village, officials reported that learning about the laws around the protection of women and children, and consequences of gender-based violence, reduced local incidences of abuse.

In Peru, communities are incorporating more discussions about gender equality into school curricula—targeting the roots of norms that make women so vulnerable to resource scarcities. And young people, both men and women, are on board. Just a few weeks ago, our team hired another teacher to help with the gender equality programming in Peru, as close to double the number of students we anticipated showed up, wanting knowledge and social change.

Global threats to health and well-being, such as water insecurity, can be daunting. But research can ignite change when the findings are returned to affected communities and inspire action. For us, social change began to happen because of partnerships between anthropologists and local women who are pushing the status quo to provide a better future for young people in their communities.

Together, we have formed a global sisterhood of academics and activists committed to addressing water insecurity and women’s health. We hope others will join us.