The Strange Power of Laughter

WHEN I WAS LITTLE, I tended to fall into bouts of uncontrollable laughter. Basically, once I started laughing, I found it very difficult to stop. The problem was particularly acute in contexts where I wasn’t supposed to laugh, when the urge to laugh would become utterly overwhelming—to the extent that I quickly acquired the moniker “Giggling Gertie.”

One of the best descriptions I have seen of this phenomenon is the “giggle loop.” This phrase was coined by a character named Jeff in the early 2000s British sitcom Coupling.

“Basically, it’s like a feedback loop,” Jeff says. “You’re somewhere quiet. There’s people. It’s a solemn occasion: a wedding. No! It’s a minute’s silence for someone who’s died. … Suddenly, out of nowhere, a thought comes into your head: The worst thing I could possibly do during a minute’s silence is laugh. And as soon as you think that you almost do laugh—automatic reaction!”

There’s nothing like getting caught in a giggle loop, where the desire to laugh builds until it bursts out at a disastrous moment. Only then do we often realize that laughter is a rather strange phenomenon. Although we usually think of laughter as a response to something funny, sometimes laughter is no laughing matter!

As an anthropologist specializing in health and medicine, laughter isn’t really in my professional wheelhouse—unless you subscribe to the view that laughter is the best medicine. My interest in the topic is more personal, not just because of my history as a former Giggling Gertie, but because it’s a behavior that is much less straightforward than it seems.

Ideally, laughter is something we share. According to anthropologist Munro Edmonson, laughter is sociable; it ideally invites a similar response. Indeed, it has contagious qualities: When we hear someone laugh, we often laugh, or at least smile, ourselves—an effect consistently shown through psychological research. This is how we ended up with canned laughter on sitcoms. Studios realized that the sound of laughter made their shows seem funnier to their audiences, while also giving them a degree of control over when people laughed.

But laughter is rather different when you’re the only one doing it. Consider actor Natalie Portman’s awkward chuckles after delivering a bad joke during her speech at the Golden Globe Awards in 2011. The 4-second laugh quickly became the subject of endless looped videos. As the cultural studies scholar Fran McDonald shows in her analysis of the incident, “laughter without humor appears to render us mechanical, terrifying, monstrous.”

WHAT’S SO FUNNY?

According to the anthropologist Munro Edmonson, the central feature of laughter is aspiration: We release a forceful puff of air as we laugh.

But laughter is also characterized by repetition. In fact, given the extraordinary variability in the sounds people make when they laugh, repetition is what makes laughter universally recognizable. This is why writers conventionalize laughter as “he-he-he,” “ha-ha-ha,” and “ho-ho-ho” (well, at least if you’re Santa Claus). Notably, this feature isn’t exclusive to English representations. Edmonson observed that laughter is represented in Russian as xe, xe, xe; in Tzotzil—a Mayan language spoken in Mexico—it’s ‘eh ‘eh ‘eh.

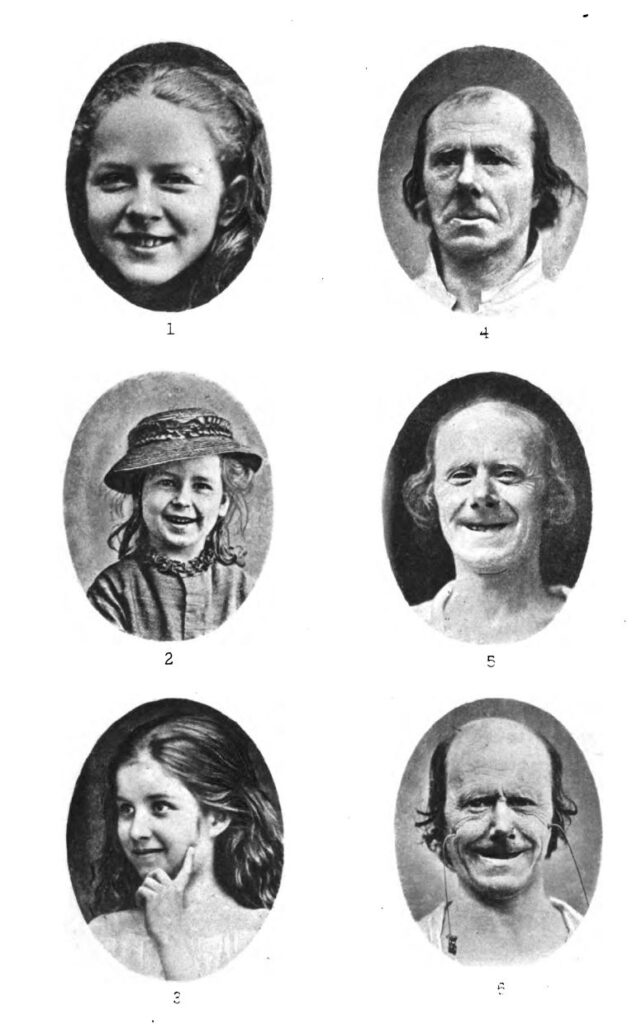

We don’t fully understand why humans make this sound when we laugh. When 19th-century biologist Charles Darwin set out to explore the biology of feelings in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, he wrote, “why the sounds which man utters when he is pleased have the peculiar reiterated character of laughter we do not know.” However, the response seems to occur well before culture is embedded in our behaviors: Recognizable laughter is evident in babies from 4 months old.

Nor is laughter unique to humans. Great apes respond to being tickled in much the same way that humans do. Of course, because chimps, bonobos, et cetera have a different vocal apparatus than humans, it sounds more like a dog panting or a person having an asthma attack or energetic sex. However, these primate sounds have the same “peculiar, reiterated character” that Darwin highlighted in humans. This is why laughter is characterized by scientists as a cross-species phenomenon.

Yet, while laughter is evident in the play of other primates, it’s unclear whether they have a sense of humor. Recent research provides evidence of a capacity for teasing through nonverbal behavior. But, as the evolutionary psychologist Robert Provine noted, “there is no evidence that they respond to apparently humorous behavior, their own or that of others, with laughter.”

Giving meaning to laughter seems to be distinctively human.

LAUGHTER AND “CIVILITY”

While some laughter is deliberate, much of it is outside conscious control—an attribute that goes a long way toward explaining the widespread Euro-American ambivalence toward the act. According to the literary scholar Sebastian Coxon, a growing anxiety about mirth is evident in the European historical record from the late Middle Ages. For example, the 16th-century Dutch philosopher Desiderius Erasmus, better known for advising children to “replace farts with coughs,” also warned against “loud laughter and immoderate mirth.”

Notably, Erasmus singled out the “neighing sound that some people make when they laugh” for particular opprobrium—an impulse evident in the contemporary tendency to compare unrestrained laughter with the cries of animals: “howling” with laughter, “hooting” in delight, “snorting” with amusement, and so on. Indeed, while the term “guffaw” might not be borrowed from animal noises, it certainly sounds like it could be.

These characterizations reveal an attempt to draw laughter into the realm of taste and civility—categories that are strongly tied to gender and class strictures. For instance, in an 1860 etiquette guide titled The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness: A Complete Hand Book for the Use of the Lady in Polite Society, readers are counseled to moderate their laughter during a dinner party so that it’s neither too loud nor too soft: “To laugh in a suppressed way, has the appearance of laughing at those around you, and a loud, boisterous laugh is always unlady-like.”

Social judgments abound not just in relation to how we laugh but what we laugh at—as an early 19th-century artwork attests. “Laughter,” etched by British artist and social commentator Thomas Rowlandson, depicts a man laughing at his cat adorned in a bonnet and cloak. The caption reads:

“Laughter is one of the most pleasing of the Passions and is with difficulty accounted for, as risibility is frequently excited from the most simple causes—as is the case with the Countryman and his Cat.”

The implication is that “unsophisticated” countrymen lack “class” and are therefore easily amused. (For the record, I am equally unsophisticated, because I will never not find cats pictured with human props funny.)

LAUGH AND THE WORLD LAUGHS WITH YOU?

Still, despite the association between humor and taste, it’s often physical comedy that gets the most laughs. It’s not a coincidence that the first truly global hit comedy was The Gods Must Be Crazy, whose sublime “Tati-like slapstick routines” drew audiences from New York and Caracas to Tokyo and Lagos, despite being widely condemned by film reviewers as apartheid propaganda.

Indeed, screenwriters have long predicted that physical humor will become increasingly prominent in Hollywood comedies because it “transcends dialogue and even most cultural differences,” and movies must increasingly appeal to a global market to produce reliable returns. (As far as I can tell, the future of Hollywood films is basically Marvel movies and slapstick comedies.)

This also helps explain the success of shows like America’s Funniest Home Videos and Total Wipeout, which largely fall into the genre of comical mishaps. “This is unbelievably stupid,” I used to declare whenever my husband watched the latter, where contestants completed ridiculous obstacle courses in the hopes of winning 10,000 pounds, and audiences tuned in to see them repeatedly being hit by objects, falling off objects, and falling onto objects. But I would laugh despite myself, because I simply couldn’t help it.

As McDonald observes, laughter disrupts the notion of a stable, coherent self—reflected in terms like “cracking up” and “bursting.” Moreover, unrestrained laughter doesn’t just signify a lack of personal control; it can be politically dangerous as well. The literary historian Joseph Butwin writes of “seditious laughter” as a weapon of the oppressed that can serve to destabilize hierarchies and power relations.

In the end, it’s clear that laughter is a deeply curious thing. It’s simultaneously the most social of human expressions and the one most disruptive of social edifices and rules. Shared, sanctioned laughter might bring us together, but unsanctioned laughter shows the cracks, revealing that we’re not quite who we think.

Editors’ note: This essay was adapted from “The Sheer Strangeness of Laughter,” published on the author’s Silent but Deadly Substack on October 23, 2023.