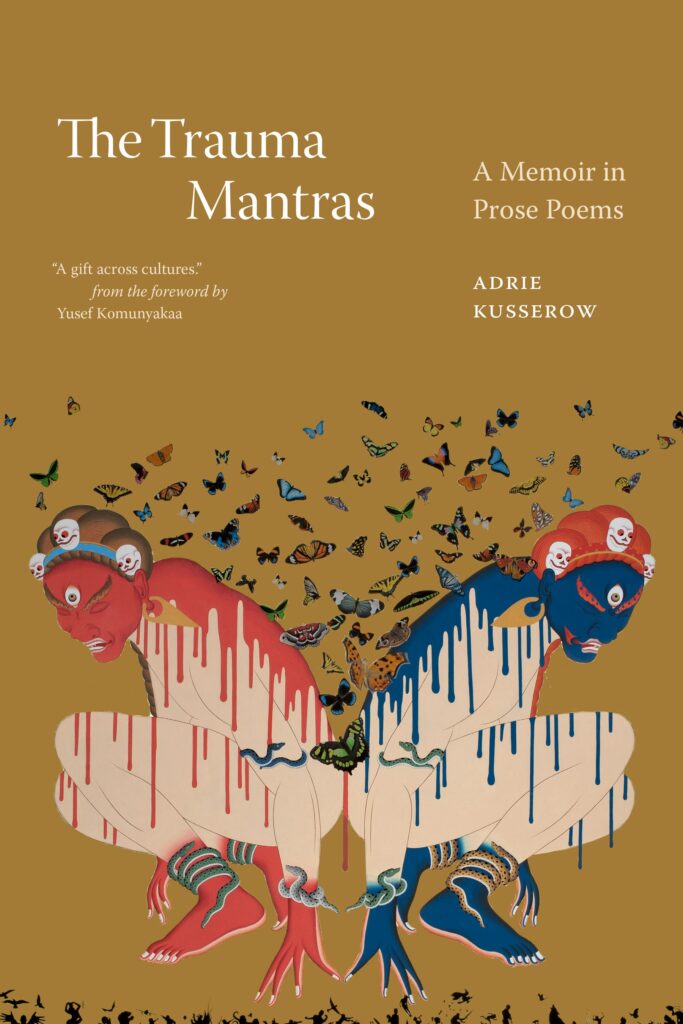

The Trauma Mantras

Excerpted from The Trauma Mantras: A Memoir in Prose Poems by Adrie Kusserow. Copyright Duke University Press, 2024. All rights reserved.

Since childhood, I have been keenly interested in different cultural conceptions of suffering and trauma. In my recent memoir in prose poems, The Trauma Mantras, I peel back assumptions many people in the U.S. hold about the self, emotions, and healing while reflecting on my experiences as a medical anthropologist in a variety of places around world.

These pieces are “autoethnographic,” meaning I explore personal experiences and connect them to wider cultural and social meanings and understandings. I reflect on working with refugees for two decades along with my own past experiences as a child and my life as a mother, daughter, and teacher.

The geographic range of these prose poems spans Bhutan, Nepal, northern India, Uganda, South Sudan, and Vermont, where I live and teach. I share insights about my struggles with fieldwork, the challenges of bringing my family into the field, the influence of technological saturation on human emotions, the stories we are socialized into about how to process suffering, and in the excerpt below, my father’s sudden death when I was age 9 and its influence on my becoming an anthropologist. Often, I bump up against the ethnocentrism of certain American talk therapeutic healing models and what I see as the globalization of Western conceptions of trauma to cultures with different understandings of distress.

As a memoir of witness and humility, I critique and gain a fresh perspective on Western approaches to the self, suffering, and healing. For example, much of my ethnographic research in Vermont focuses on organizations attempting to heal refugees of trauma and the Western, individualistic assumptions these organizations hold around self, emotions, trauma, and suffering. Much of my work explores the often new and Americanized stories refugees are socialized and expected to learn, process, and believe in about their own suffering.

Throughout many of these prose pieces, readers can sense my hunger to bust out of such narrow confines. I often hint at the importance of widening understandings of the American self. In these poetic meditations, I travel the world, exploring the desperate fictions that “East” and “West” still cling to about each other—the stories we tell about ourselves and obsessively weave from the dominant cultural meanings that surround us.

INSTRUCTIONS FOR DOING FIELDWORK TRACKING AMERICAN BUDDHISTS FOR INTERVIEWS AT THE STUPA

Thimphu, Bhutan

Always remember, as a fellow Westerner, to them you are a predator, an irritant, an annoying reminder.

Keep a radius of at least 10 feet.

Play nonchalant, even disinterested, working your peripheral vision for all it’s worth.

When stalking, feign interest in a postcard of the Himalayas.

Remember it’s their nature to want to distinguish themselves from you.

Beware: Almost any posture will seem like hovering.

You are dealing with egos that crossed continents to flee you.

Give them a chance to take you in.

Let your presence settle in their vicinity, eventually diffusing, as does any offensive perfume. Resist every impulse to initiate conversation too early.

Once they see you are ignoring them, they will loosen.

This is the time for one long stare, a five-second zoom of the face to assess their level of approachability.

This will help you tailor your greeting to their specific needs.

They will sense you want contact. Expect nonverbal defenses to go up (exaggerated absorption in the Dharma manifested through aggressively working the prayer beads or circumambulating the stupa more briskly than usual).

Approach tentatively.

Remember their impulse is to flee. Images of their own desperate quests for meaning will pelt their brain, their own prized uniqueness suddenly seeming generic—at which point armies of neurons will rush into the frontal lobes feverishly rationalizing how they are still different, still the only real Western Buddhists in town.

From here, you’re on your own. Good luck!

THE DAY I REALLY BECAME AN ANTHROPOLOGIST

Underhill Center, Vermont

I was 9 years old. My father still a handsome, lanky Prussian god when an 18-wheeler crushed his green Volkswagen bug. After that, I changed planets, and all was new and strange. Most days I was dealing with the terrors of my body: the sudden sweating, the crawl of coy, the rocket blast of diarrhea, the prickled dread up my spine blossoming through my chest. Rush to hide the shame.

I knew I was a freak, but I had to survive on this planet. So I watched my classmates nonchalantly doing their human things—eating their lunches, passing notes in class.

I didn’t like climbing around the cold, sticky edges of my cave all fucked up and lonely like Gollum. So when I had to be conscious, emerging like a corpse from my Valium/Benadryl haze, I tried my own version of participant observation: kickball at recess, hot lunches, Girl Scouts, bumpy bus rides, and tag. I tried focus groups—four girls giggling at an overnight I hosted once a week. I studied them. I did whatever they did, my sole mission to analyze their speech, tone, body language, smell, rhythm. My own cells absorbing their logic. I’d bait them with questions and watch the spool of their rationales unwind, the ones they took as normal, natural.

That’s when I really became an anthropologist. When I could answer any question in the way they might by ad-libbing off their chill philosophy of life, the base layers even they weren’t aware of.

I called it burrowing, sneaking inside the mind’s caves, viewing the landscape from my classmates’ perspective. Strangely, it made me feel physically warm. I grew addicted to that feeling, to the point where I’d space out in class.

Participant observation: You plunk yourself in the middle of the bush in South Sudan, at a stupa or high school in Bhutan, in a nongovernmental organization in Darjeeling, working and playing beside others but simultaneously observing. When you catch yourself getting a little lopsided (too much getting lost in other people’s world or too much standing aside and observing), you lean the other way. It’s a delicate balance I’ve spent my whole life perfecting. I’m not sure how I could ever turn it off.

FONTANELEGY

After birth, when they finally brought my daughter back, dry, pink, and powdered in a Princess Pretty onesie, already she smelled alien, like T.J. Maxx, like Pampers, so I huddled like an ape over her tiny skull, mouth grazing across her scalp, frantically searching for her soft spot, the fontanel, its warm, pulsing cave no bigger than a dime, barely covered with a slip of furry skin.

Lips pressed against it, I felt her heartbeat’s manic flutter in my throat, unfinished nerves sparking and misfiring, tiny wings of her blood pulsing. She latched on, sending me a fierce Morse code through the language of suck.

Twenty years later, an anthropologist, I roam Earth’s skull with the same urgency as the day I first held her, feeling for the vulnerable spots, the cultural fontanels, the warm parts that throb, back alleys where shapes shift, asylees huddle, girls pass like shadows between spirit and flesh. Where refugees hide in comas and won’t come out until it’s safe, the tender places that swell between borders, where the status quo groans, the internet is sketchy. Sherpas and shamans caught between YouTube and soul loss, avatars and graveyards, iPad and axe. Where globalization creeps forward, drapes thinly across a village’s back.

Bless the liminal, those speaking in tongues, the dented and supple.

Bless the cartilage, the soft spots built into evolution that refuse to harden, the places on this planet with mouths hanging open, the dark fontanels that still ripple like wide-eyed ponds, the skull plates hovering like sharks.

This excerpt has been lightly edited for style, length, and clarity.