The Myth of the Virgin Rainforest

The little village of Pa Lungan sits in a grassy clearing, high in the hills of Malaysian Borneo, in a region called the Kelabit Highlands. The people here—a few dozen—belong to the Kelabit tribe, one of more than 50 Indigenous groups living on Asia’s largest island. They have sturdy wooden homes with slat glass windows, metal roofs, kitchen sinks, and TVs. Generators and solar panels power a few lightbulbs, laptops, and mobile phones (typically used to play music and games). Most households have a kitchen garden, an outdoor toilet, a cold-water shower, and a laundry line. A patchwork of coops and fences keeps chickens and buffalo in check. Just beyond these homes and yards lie rice fields fed by mountain waters and hemmed in by trees. It’s a tidy, orderly life in Pa Lungan—and it’s an easy walk to some of the most biologically diverse rainforests on Earth.

The Kelabit, like their ancestors, move fluidly between the village and the forest in a culture where notions of domestic and wild intrinsically overlap. Villagers plant fruit trees in the forest; they move wild herbs from the jungle to their kitchen gardens. “Daily living” and “the bounty of the forest” are deeply intertwined, as the Kelabit anthropologist Poline Bala, based at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, explained to me. In the past few years, new research has begun to shift scientific perspectives—and my own—of the Borneo landscape. It is not the wild, untamed place many people have long assumed it is. Rather, the rainforest we see today bears the marks of long-term human intervention.

In 2006 and again in 2013, I visited Pa Lungan as a journalist. [1] [1] Reporting for this story was made possible in part by a fellowship from the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ). During my initial visit, I became acquainted with a villager named Walter Paran. He is a thoughtful middle-aged man with slow and deliberate speech, a calm composure, and muscles shaped by a life lived off the land. In 2014 I wrote about Paran in a travel story that documented my search to find him after the intervening seven years to see how he and his neighbors were surviving in the face of widespread logging.

When I asked Paran questions about his life on both of my trips to the highlands, he took me on walks to convey his sense of place. Everything he knows and needs to know about who he is and who his ancestors were can be found in the physical world around him.

Right from Paran’s door, narrow footpaths lead through the village and into the woods where his forefathers lived. Beyond that is a damp, dark forest of ancient old-growth trees that grow straight and tall, their trunks as wide as pickup trucks. A dense canopy of branches forms a shield against the equatorial sun. Below these trees is a complex undergrowth of thorny plants and winding vines, ferns with coiled fronds, and pitcher plants that swallow flies. The ground is slick with mud, and the air smells musky. Giant rats and wily snakes hide from sight. Leeches stand upright, twisting and reaching for anything that moves. In that ancient forest, wild boars root about the forest floor, and deeper inside the jungle, rarely glimpsed honey bears leave their tracks.

When I saw this forest for the first time in 2006, it appeared to me a wild, primeval place. When I returned in 2013, I began to see the forest in a finer-scale resolution, finding marks of history and culture throughout the landscape. I learned how the Kelabits and their ancestors have shaped this jungle through centuries of work.

On one of my afternoon walks with Paran in 2013, he paused to hack at rattans and other palms with his machete, knocking their sturdy stems to the ground. He noted which plant’s shoots taste fresh and sweet, and which one’s leaves make a great roof. He pointed out a tall umbrella tree. Its sap is used to make fire, he told me.

“Here,” he said as he handed me a sliver of edible palm shoot. “You can try a bit.” It was kind of pasty. My mouth puckered.

“When you go out in the jungle, you must know the things you can eat,” he told me. He also showed me trees that fed his ancestors: durians (a tropical fruit with a hard spiky shell), langsat (small oval fruits with tough skin and juicy flesh), and jackfruits (bulbous, spiny fruits with sweet-tart yellow insides). “They planted all these things,” Paran said, right there, in the forest.

In another spot, he pointed out where, long ago, his relatives lived in a community longhouse. Earlier generations of Kelabits (and some still today) occupied long, rectangular wooden homes on stilts. When those wooden homes caved to age, or the people felt the urge, they would abandon that longhouse and build a new one in another spot in the forest. The vegetation always grew back around the old homesite, but it was still considered young by Kelabit standards. “That’s why you see the trees are small,” Paran said. “We don’t consider it forest yet.”

I hadn’t noticed. I was still somewhat beholden to the idea of a “virgin rainforest.” But Paran was showing me a world in which there was no clear distinction between the cultivated and the wild.

For more than a century, scholars, naturalists, and travelers understood the Borneo rainforest to be a pristine place virtually untouched by human hands. But research now suggests that over millennia much of the forest was cultivated and shaped by human intervention. And today change is happening at a breakneck pace as new roads slice through this jungle and connect Kelabit villages with cities on the coast. Logging trucks beat down those roads while huge tracts of forest are razed. In addition, the Kelabit diet is shifting due to an influx of packaged foods and ingredients now available from the coast. Scientists say the Kelabit environment is changing faster than ever before. And current scientific research on this forest is far more than just a documentation of the past in comparison to the present; it’s a critical lens on what’s at stake for the people of highland Borneo. Research provides a testimony for saving not only this rainforest but the cultures nestled within it.

“It was an assumption—almost an article of faith—amongst many biogeographers, ecologists, and paleoecologists that the great regional rainforests were, at Western contact, the product of natural climatic, biogeographic, and ecological processes,” wrote paleoecologist Chris Hunt, now based at Liverpool John Moores University, and his colleague, Cambridge University archaeologist Ryan Rabett, in a 2014 paper. “It was widely thought that peoples living in the rainforest caused little change to vegetation.”

New research is challenging this long-held assumption. Recent paleoecological studies by Hunt and other colleagues show evidence of “disturbance” in the vegetation around Pa Lungan and other Kelabit villages, indicating that humans have shaped and altered these jungles not just for generations—but for millennia. Borneo’s inhabitants from a much more distant past likely burned the forests and cleared lands to cultivate edible plants. They created a complex system in which farming and foraging were intertwined with spiritual beliefs and land use in ways that scientists are just beginning to understand.

Samantha Jones, lead author on this investigation and researcher at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, has studied ancient pollen cores in the Kelabit Highlands as part of the Cultured Rainforest Project. This is a U.K.-based team of anthropologists, archaeologists, and paleoecologists that is examining the long-term and present-day interactions between people and rainforests. The project has led to continuing research that is forming a new scientific narrative of the Borneo highlands.

People were most likely manipulating plants from as early as 50,000 years ago in the lowlands, Jones says. That’s around the time humans likely first arrived. Scholars had long classified these early inhabitants as foragers—but then came the studies at Niah Cave. There, in a series of limestone caverns near the coast, scientists found paleoecological evidence that early humans got right to work burning the forest, managing vegetation, and eating a complex diet based on hunting, foraging, fishing, and processing plants from the jungle. This late Pleistocene diet spanned everything from large mammals to small mollusks, to a wide array of tuberous taros and yams. By 10,000 years ago, the folks in the lowlands were growing sago and manipulating other vegetation such as wild rice, Hunt says. The lines between foraging and farming undoubtedly blurred. The Niah Cave folks were growing and picking, hunting and gathering, fishing and gardening across the entire landscape.

Up in the highlands, a somewhat parallel story emerged centuries later. Jones, Hunt, and their colleagues have documented major fires between 6,000 and 7,000 years ago. The evidence is limited—and it could be explained by natural events—but it could also indicate people were setting fire to the forest and clearing areas to plant edible fruits and palms. By 2,800 years ago, researchers say, there were more frequent fires and numerous sago groves that could have belonged to the Kelabit or the Penan, a nomadic group living in the same forests who still rely on sago today.

“The Cultured Rainforest project has shown how profoundly entangled the lives of humans and other species in the rainforest are,” says University of London anthropologist Monica Janowski, a member of the project team who has spent decades studying highland Borneo cultures. “This entanglement has developed over centuries and millennia and succeeds in maintaining a relatively balanced relationship between species.”

Borneo’s jungle is, in fact, anything but untouched: What we see is a result of both human hands and natural forces, working in tandem. The Kelabit are a little bit farmer and a little bit forager with no clear line between, Janowski says. This dualistic approach to land use may reveal a deeper human nature.

“Scratch any modern human and you will find, under the surface, a forager,” she says. “We have powerful foraging instincts. We also have powerful instincts to manage plants and animals. Both of these instincts have been with us for millennia.”

And yet, age-old traditions can shatter in an instant. In one day, trucks and chainsaws can dismantle the delicate balance of forest life that tribes have fostered over centuries. When loggers finish clearing a patch of land, nothing remains intact. The dense, dark forest canopy ends abruptly in a line across the horizon; beyond that is a field of stumps. The sun beats down where it never could before.

Paran showed me spots where his ancestors marked the land with messages for future generations. They piled small rocks into mounds, and they built upright stones (menhirs) and table-shaped slabs (dolmens)—all forms of etuu, or long-lasting signs on the landscape that indicate people have lived here for generations. These etuu are scattered across the highlands, and they are threatened by corporate-owned bulldozers as are the trees, plants, and people.

Roughly 80 percent of Malaysian Borneo’s rainforests have been logged or degraded in the last half-century, largely to clear space for commercial plantations growing palm oil—used around the globe in everything from cookies to shampoo. Oil palms don’t grow well near Pa Lungan, which lies at about 2,800 feet; forests near this village are simply being razed for timber. Logging and the rapid expansion of plantations is changing the Kelabit environment “at an unprecedented rate, not experienced before in archaeological or paleoecological records,” says Jones. With such deforestation of the world’s tropical forests comes loss of species diversity, loss of food and medicinal sources, increased risk of severe flooding to cleared areas, and significant destruction of the world’s carbon stock.

When delegates from 142 countries met for the World Forestry Congress in September 2015, they adopted a declaration stating that forests “are more than trees.” Forests are, in fact, critical to climate change adaptation and “fundamental for food security.” Borneo’s rainforests exhibit this through the vast diversity of foods they foster, Hunt says.

Not only does scientific research in the Kelabit Highlands underscore Hunt’s point about food security, it also lends evidence that can help arbitrate land disputes today. The Cultured Rainforest Project and other studies highlight the reciprocal relationship between people and place. They provide arguments for saving the forest and the peoples who steward it.

“There is no legal land ownership in the Kelabit Highlands,” Janowski says. There are no titles or documents; territory is communal, and people allow others to use their resources “so long as permission is asked.” But logging violates this custom. “For the Kelabit, logging is tantamount to stealing,” she says. And for the Penan, “loss of the forest is the loss of their entire world.” Locals are starting to see forest destruction as a violation of human rights. Indigenous communities have filed dozens of complaints with the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia based on land disputes, and they have won many cases in court, says Ramy Bulan, an associate law professor at the University of Malaya.

Villagers in Pa Lungan dread the loss of their forest. A few years ago, the Malaysian government expanded a nearby national park, protecting the jungle immediately surrounding Pa Lungan. Fears are diminished—but not gone.

“I am worried about logging,” said Supang Galih, Paran’s neighbor. She runs a homestay and a restaurant that serves wild jungle foods—a selling point. She is a strong advocate for protecting Kelabit cultural heritage. “We are very lucky,” she told me, because the forest remains intact, for now. “We still have trees to cut for firewood, and we still have the jungle where we can look for our food, and we still have our forest where we can look for our meat to eat,” she said. “If we have no more jungle, or no more forest, these things will be gone.”

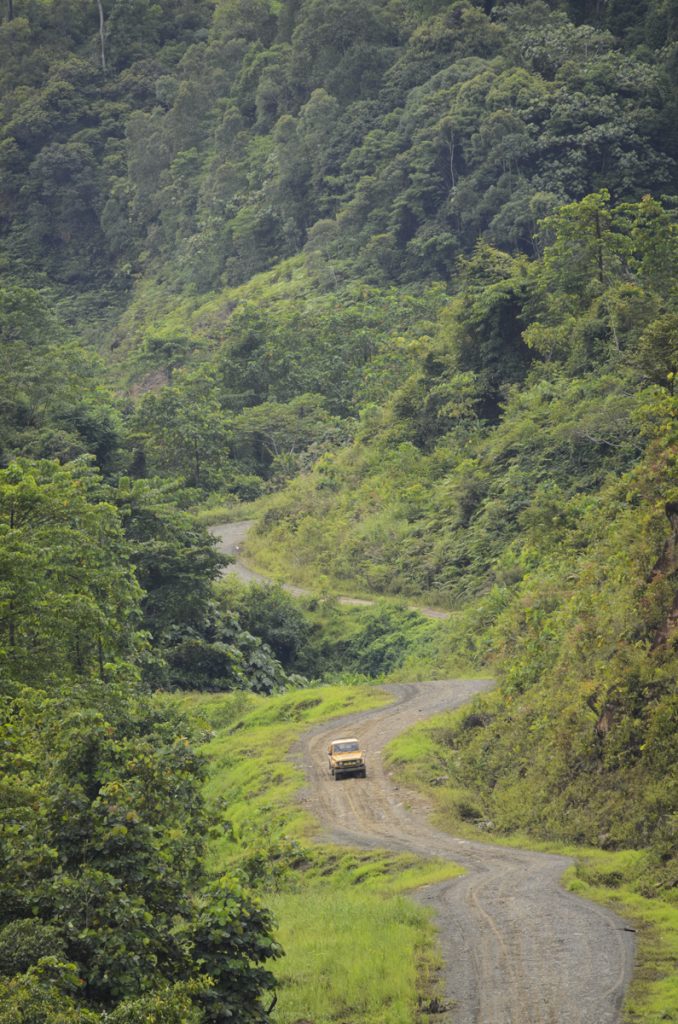

Touting it as “progress,” the Malaysian government aims to build more than 1,800 miles of infrastructure across Borneo between now and 2020. When a road goes in, trees go out—and so do indigenous knowledge and ancient ways of life.

But it’s easy to love and hate a road at the same time. While roads signal destruction, they provide opportunity too. They create access to markets, cities, education, and jobs. They bring frozen chicken wings to the jungle, and they shuttle students away to school in distant cities.

This tug of modernity permeates Pa Lungan life today. For example, the village has no school. The children study in Bario, the nearest town—little more than an airstrip and a string of shops surrounded by homes within a valley of rice paddies. The students typically stay in a dormitory and return to Pa Lungan every week or two. Until recently, the journey required a five-hour hike on a footpath through the jungle. But a new road, finished in the past year, can cut that time to less than an hour—if the rains don’t wash it out. “Of course the younger generations do need education,” Supang said. If people never leave the village, they will “know nothing about the outside world. … So we do need our younger generations to have the knowledge of what the present life is.” And, what the future might hold.

Understanding places like this is critical, Janowski says, because “there is in fact no one-way journey from a ‘primitive’ foraging past to a ‘modern, civilized’ farming present.”

Getting to know Paran taught me this lesson firsthand. When I first set foot in the Kelabit Highlands and looked at the trees around me, I saw a tangle of seemingly wild forest. But Paran taught me there is orderliness to that chaos.

He showed me food and poison, ropes and rooftops, wild palms and cultivated fruit trees his ancestors had planted. He saw nuances in the environment that I hadn’t begun to discern. Paran saw his home, and that of his ancestors.

He hopes it will be there for his children, too.

This article was republished on discovermagazine.com.