Rubber Barons’ Abuses Live On in Memory and Myth

After he had put them into a deep sleep, the tigre negro entered the camp and killed them all, slashing their throats. It sucked the blood out of them. Only one saved himself by hiding in the forest. From there he heard his companions screaming. That’s how the tigre negro killed the rubber tappers.”

I heard that story from my father when I was a boy, sitting on the palm wood floor of our house on the island of Sarapanga in the Marañón River in northeastern Peru. With smoke from my father’s pipe wafting around us and the river flowing by just meters away, the tale of the tigre negro (literally black tiger, a reference to the black jaguar) capped his late-afternoon storytelling, after which he’d send us off to bed.

Years later, I heard it again as I visited villages with my colleagues from Radio Ucamara, a small station in the port town of Nauta. The members of the radio station staff (including myself, one of the authors, Leonardo Tello) are of the Kukama people, the Native group that predominates in villages along the lower Marañón. The station primarily serves Kukama communities.

When I first listened to it as an adult, the story struck me as odd. The reclusive jaguar is a selective predator, taking only the prey it needs. But gradually, the tale of the animal that slaughtered humans and drank their blood revealed a terrible truth. The tigre negro was not a feline of the forest but something more sinister—a metaphor for a rubber baron. The story captured the living memories of an era when rubber, the once-precious natural latex that drove the Amazonian economy, led to the death or forced displacement of thousands of Indigenous peoples. That reality is as vivid now as it was a century ago when the rubber boom was at its peak.

“Indigenous mythic histories are often non-linear. They’re not necessarily chronological. They may not be concerned so much with telling exactly what happened but with trying to socialize the events of the past so they can be placed into collective memory in ways that make sense within the Indigenous world view,” says anthropologist Jonathan D. Hill of Southern Illinois University, who has collected stories about the rubber boom era in Venezuela. “I think that’s a healing process.”

Myth, says Hill, offers a way for Indigenous peoples to interpret their own histories and maintain their cultural identity within Latin America’s predominantly non-Indigenous societies.

For Indigenous peoples in the Amazon region, the rubber era was a particularly traumatic part of their collective history.

The rise of commercial manufacturing in Europe and the United States in the 19th century triggered an economic boom in South America by creating an enormous appetite for rubber to make tubes, tires, belts, gaskets, and other products. The Brazilian cities of Manaus and Belém, as well as Peru’s Amazon port city of Iquitos, still bear traces of the fortunes made in the late 1800s before British travelers spirited thousands of rubber tree seeds to London. Once they were germinated, the seedlings were sent to Asia, where plantations were sown.

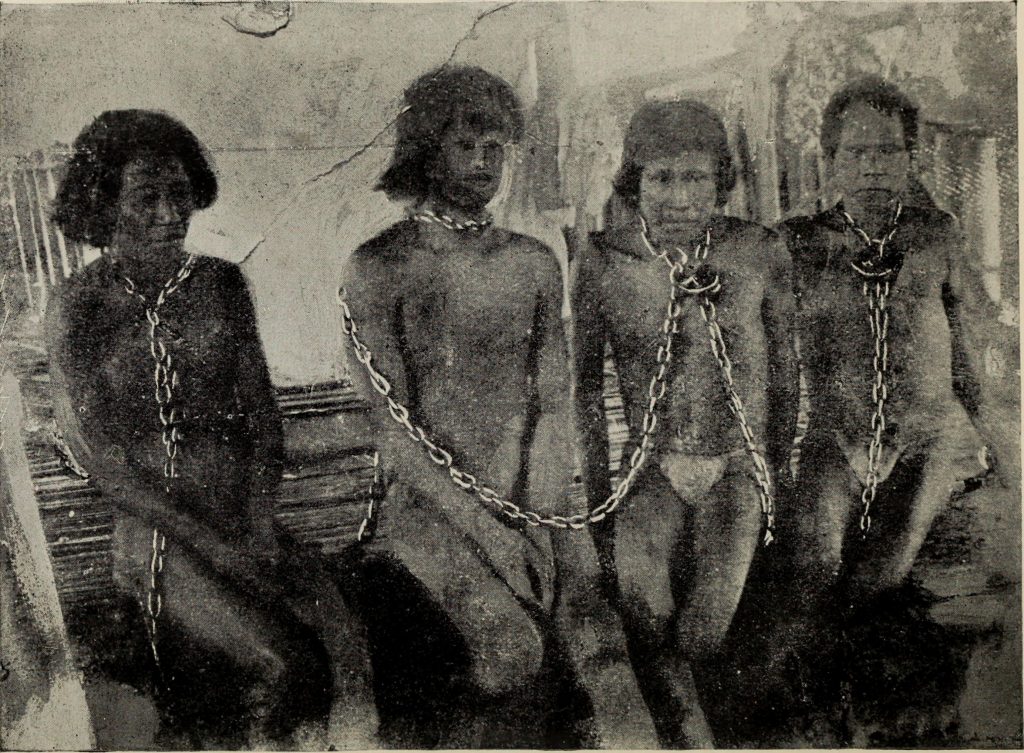

But the rubber barons’ wealth came at the expense of forced labor—some of which was outright slavery. Thousands of Indigenous men, women, and children died while subjected to this work or were murdered by overseers when they failed to deliver their quota of latex—or when they rebelled.

One of the most brutal rubber barons was the Peruvian Julio César Arana, who operated in a large swath of land along the Putumayo River during the first decade of the 1900s, taking advantage of lawlessness in an area where the border between Peru and Colombia was undefined. Accounts of the rape, torture, and murder of Indigenous laborers eventually reached England, where Arana’s Peruvian Amazon Company was registered. Press coverage and pressure from a human rights organization there led to an investigation by British diplomat Roger Casement.

Casement’s damning report, filed with the British Foreign Secretary in 1911, triggered another investigation in England, since three of the company’s directors were British. But it had little impact in Peru, where those responsible for the abuses went largely unpunished.

Instead, the end of the rubber boom in this region of the world was a matter of economics. As Asian plantations began producing more latex at a lower cost, rubber tappers—who worked from scattered trees in the forest—could no longer compete, and the Amazonian boom went bust.

Nevertheless, rubber production—and the abuse of Indigenous laborers—continued in Amazonian Peru on a smaller scale, finally dwindling away in the mid-20th century.

Some Kukama villagers along the lower Marañón River tapped rubber as recently as the 1950s and 1960s. The villagers were not slaves but rather laborers indebted to patrones (landholders and bosses) in what is now the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, a huge protected area encompassing a seasonally flooded expanse of forests and wetlands in Peru’s Loreto region.

Although the last of the rubber tappers do not remember the peak of the era, when Arana ruled, the collective memory of that time remains alive in stories they heard from their parents and grandparents, and in myths such as that of the tigre negro.

Even now, when the descendants of that era’s victims tell tales of torture, rape, and murder suffered at the hands of rubber barons, their eyes fill with tears, says Stefano Pau, a scholar in Latin American literature and cultural studies based at the University of Cagliari in Italy. Pau has collected stories and myths about this time period in Nauta and in communities along the Ampiyacu River, a tributary of the Amazon in Peru.

I also experienced the emotional pain that lives on from that era. When I sat down, audio recorder in hand, to ask my father to tell me about his life during those years, he looked me in the eye and began by telling me that everything was good back then. Then his voice broke, his hands trembled, he bowed his head, and he began to cry. As I listened, my heart ached. I became angry. I wanted revenge. That afternoon changed my life.

Since then, my colleagues at Radio Ucamara and I have collected more than 70 personal accounts of the rubber era. Others are engaged in similar efforts, including artists such as Huitoto painters Rember Yahuarcani and Brus Rubio. Peruvian anthropologist Alberto Chirif of Iquitos recently edited two accounts of the era told by Ramiro Rojas Paredes—a Huitoto Murui man born in 1923 in the heart of rubber country—to his grandson, Alex Acuña, before Paredes died in 2008.

Besides the story of the tigre negro, which reflects the cruelty of the rubber barons, the stories we have collected contain other figures from that era who have become interwoven with the Kukama spirit world. Such tales echo the past and connect it with current events along the Marañón.

Stories of ghost ships—brightly lit boats with lavish parties on board that Kukama fishermen see on the river at night but that disappear without a trace—are a reminder of the boom times, when the patrones traveled in luxury made possible by the exploitation of Indigenous workers.

The places where fishermen tell of seeing these boats are often sites where latex was loaded onto ships or where some other rubber-related activity occurred. And the myths surrounding these ships of old have re-emerged with the arrival of oil barges and high-end tourist cruise ships that now ply the river.

Other common lore features a pink river dolphin that takes the form of a light-skinned man wearing boots and a broad-brimmed hat who appears in communities, courting the women and impregnating them.

Although pink dolphin myths predate the rubber era, this version of the story harks back to when male laborers would spend long periods of time in the forest while their wives and children, left behind in the village, were at the mercy of the patrones. “I saw how they arrived at the community’s port, where my aunt and my cousins were washing in the river,” recalls 64-year-old Víctor Canayo Pacaya, who grew up in a village along the Marañón but now lives in Nauta. “They grabbed my cousins and their mother and raped them. I saw them from my hiding place in a guayaba tree.” If a man returned home to find his wife carrying an unborn child that was not his, the pregnancy would be blamed on the pink dolphin.

Many of the women and girls who experienced such violence are grandmothers and mothers now, but their stories have never been heard. Nothing has been done to reconcile the past or heal those wounds, and their daughters and granddaughters often suffer similar sexual aggression when they travel from their communities to cities to work as maids, sometimes in the homes of the rubber barons’ descendants.

In 2012, a century after Casement wrote his scathing report, the Colombian government—in a ceremony at La Chorrera, which was at the heart of the Arana empire and which is located in what is now Colombia—officially apologized for the atrocities Indigenous peoples suffered during the rubber era.

But the apology did not reach the ears of many of the people whose lives are still marked by the upheaval, and discrimination and humiliating treatment continue. Human trafficking and child sex tourism, oil spills, and loss of territory are modern reminders that the era of pain and exploitation has not ended.

The densely forested border between Peru and Brazil has the largest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples—tribes that generally shun contact with outsiders—in the world. Many are descendants of people who fled into the forest to escape the violence unleashed by the rubber barons.

Although there has been some acknowledgment of the tragedy by government officials and even in literature—Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa’s novel, The Dream of the Celt, is based on Casement’s story—recognition of the moral dimension of the rubber boom and its aftermath has been slow to come.

My colleagues at Radio Ucamara and I would like to see the rubber era included in the Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion (Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión Social), a new museum in Lima that is mainly dedicated to the historical memory of the political violence of the 1980s and 1990s.

Some Indigenous rights activists are also calling for compensation for the violence, an idea that is still in the early stages, according to Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples.

During an official visit to Brazil in March, Tauli-Corpuz recommended that a national inquiry be made into the living situation of Indigenous peoples. Such an inquiry could allow for deeper exploration into the current situation of Indigenous peoples as well as examine the structural and historical roots of the problems they face, Tauli-Corpuz says.

The generation that holds memories of the rubber era is leaving us—my father is now 98, and several people who told us their stories a few years ago have since died. When young people read about those decades in history books, they learn names and dates, but they do not learn how deeply the horror affected—and still affects—their grandparents, their parents, and themselves.

It is important to listen to the accounts of older men and women, but we must also ensure that both the true and the mythical stories reach our youth. Many of them do not understand why Indigenous peoples in the Amazon still suffer insults and discrimination.

“The mythologization of history is as much concerned with the moral dimension of the past as it is with factual reiteration of what happened,” Hill says. With these stories, he adds, people “no longer understand themselves as simply descendants of mythic ancestors. They’re people who are descended from the survivors of a traumatic historical past.”

Editors’ note: This story was produced through a collaboration between Leonardo Tello Imaina, the Kukama director of Radio Ucamara, who grew up along the Marañón River and whose parents experienced the end of the rubber era, and Barbara Fraser, a freelance journalist based in Lima, Peru.