Fighting for Reproductive Rights in Retirement

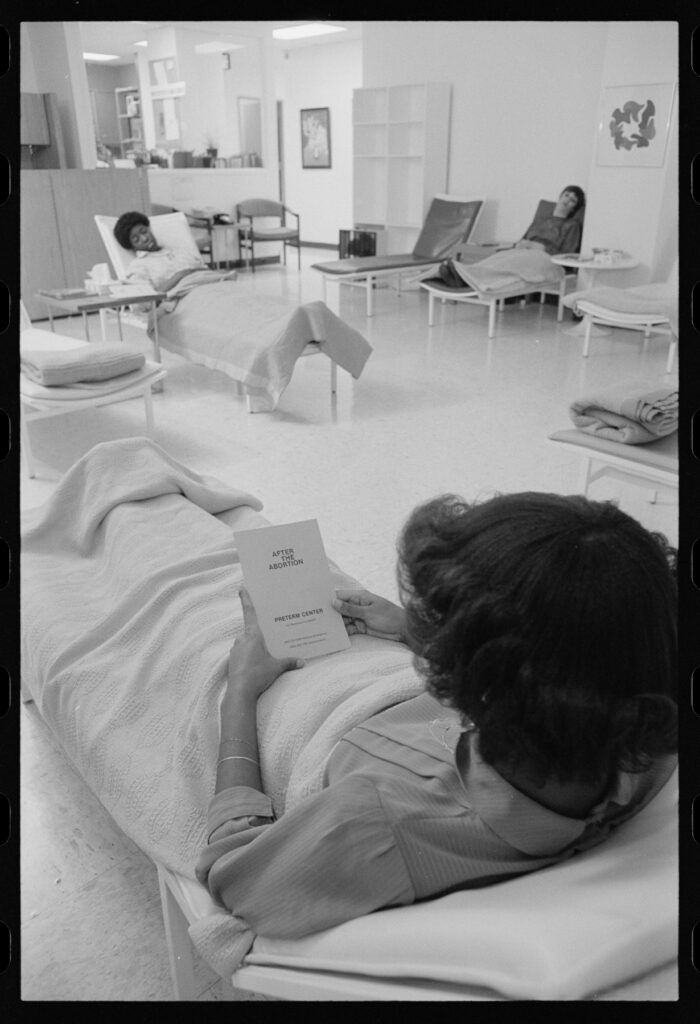

Kansas, 1957: Three friends, all 17, get pregnant in their senior year of high school. One, named Bea, has the baby and marries the young man who impregnated her. She doesn’t make it to college—a huge regret by the time we meet 64 years later. Another gets a back-alley abortion. The third kills herself.

“My father said that I could either get an abortion, like my friend, or marry the guy,” Bea says to me. [1] [1] All names of interviewees have been changed to protect their identities. It is October 2021, and we are eating lunch at her dining room table in a retirement community in Phoenix, Arizona. “Well, we got married,” she adds, “but we divorced a year later because it wasn’t right.” We are sitting with Sondra and Alice, who Bea met a decade ago when they all moved to the neighborhood. Sondra grew up in Pennsylvania, Alice in Montana.

“I thought about getting an abortion when I was pregnant with my first child too,” says Sondra. She is the oldest of the group at 89 and shares that she had five children with an abusive partner, a veteran who drank too much and who repeatedly cheated on her. She left him when their last child was 8 months old, after she discovered he had stolen a large portion of their savings.

I met Bea, Alice, and Sondra in mid-2020 when I logged into the monthly Zoom meetings of their neighborhood’s Democratic Club as part of my ethnographic research on retirement in the U.S. Southwest. At the time, they were gearing up for a tough election, trying to elect Joe Biden as president and Mark Kelly—who was running for John McCain’s former seat—as an Arizona senator. Their club hosted local Democratic candidates, procured lawn signs to hand out around the neighborhood, raised money to send to local and national campaigns, and held events to talk to their friends and neighbors about the Arizona Democratic Party. The club had grown since 2016—a remarkable change for an age-segregated community that has mostly voted Republican since it opened in 1960.

This has partly been due to the demographic makeup of the community: mostly White, middle-class retirees whose political concerns have historically centered around keeping taxes low. But in the past five years, as reproductive rights have increasingly come under threat in Arizona and across the U.S., a different political consciousness has been taking shape.

In my conversations with women like Bea, Sondra, and Alice about reproductive freedom over the decades—what has changed and what has stayed the same—I have gained a sharper understanding of what’s at stake in the ongoing fight for the legal right to abortion.

The Democratic Club participants I met lived in a community composed of people from all over the United States and Canada who migrated from where they had raised their children and moved to Phoenix in older age. For many, friendships in the neighborhood structured their daily lives. And participating in politics was a way to find community with like-minded people.

By the time I moved to the neighborhood in 2021, the women in the Democratic Club were tired: The contentious 2020 election had fractured a sense of goodwill in the community, caused arguments in public spaces, and even led some to sever ties with friends, neighbors, and relatives. In conversations at Starbucks or after the monthly club meetings, some mentioned they wanted to take a break from doing politics.

It’s up to the younger generations now, many told me. They wanted to play mah-jongg with their friends and not worry about who had voted for whom. They wanted to focus on their art or dance classes. They wanted, in other words, to make the most of the retirement they had worked to achieve. These women had spent decades taking care of husbands, children, and aging and ailing parents. Now, they wanted to focus on the present.

But they had spent too long organizing their friends and neighbors and caring about politics to look away as reproductive rights have become increasingly politicized and constrained.

On March 22, 2022, Arizona lawmakers passed SB1164, which made abortion past 15 weeks illegal. Three months later, Roe v. Wade was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. Soon after, then-Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich filed a motion to lift a 1973 injunction on a total abortion ban from 1864, passed before Arizona was a state and before women had the right to vote. And he succeeded: On April 9, 2024, after slowly making its way through the courts, the 1864 total ban became the controlling law. However, by then, even the most conservative Arizona constituents’ zeal for a total ban had waned, and state legislators managed to repeal it a few weeks later. Since then, SB1164 and the 15-week ban has been the rule. Yet, in the weeks that the 1864 law stood, much of the political landscape, including in the retirement community in Phoenix, was thrown into a frenzy.

SB1164 has shifted people’s perspectives: Since it passed, polls have consistently indicated that Democratic politicians are gaining ground in Arizona, and an amendment to the state constitution that would enshrine abortion as a right has received more than enough signatures to be placed on the ballot in November. Concerns about reproductive rights have punctured through political divides in the neighborhood. One woman told me that in her bridge club—where politics is usually a banned topic due to how contentious it has been—even the players who are Republican are horrified by the law. Although it would not directly impact their bodies, women in this neighborhood fully appreciate what it means to be without bodily autonomy: They lived it.

In media about places like the retirement community in which I conducted research, journalists are quick to focus on residents’ sex lives. Some note that The Villages, a retirement community in Florida, has the highest rate of sexually transmitted diseases per capita than any other zip code in the United States. Though untrue, it is often the punchline to the story.

But as I have learned, for many women of retirement age, sex and sexuality had been, throughout their formative years, something repressed, something to be feared and discouraged. For them, getting pregnant might mean entering a marriage with the goofy kid you lost your virginity to or getting a dangerous illegal abortion.

Even my friends in Phoenix who grew up after abortion was legalized did not always have easy access to it. Joanne, who is in her 60s, described coming of age “on the cusp” of social changes that rippled out from Roe. Abortion was legal when she grew up in Missouri, got married, and became pregnant. But when she miscarried and found herself hemorrhaging in a local ER, her Catholic physician refused to perform a common surgical procedure called dilation and curettage, or a D&C. Joanne had to cross the state line into Illinois to get the care she needed to survive.

Joanne shared this story with me as if discussing an unusual weather phenomenon: only slightly out of the ordinary. Over Zoom, she chuckled when my mouth dropped open. Stories like hers are common in the news today, but I was still shocked that she had come close to bleeding out in a hospital parking lot because her doctor refused to abide by the laws protecting her right to receive a life-saving abortion.

When I asked my friends and other women in the neighborhood what issue galvanized and shaped their political activism, none of them said abortion. Yet our conversations often spiraled into resounding echoes of how a lack of access to reproductive care had impacted other parts of their lives. I came to understand how, for some of these women, a sense of powerlessness around reproductive choice was tied to a deep sense of shame around sex and sexuality.

During my time in Arizona, I spent a lot of time with Bea, Alice, and their boyfriends. Alice is 80 and lives with Michael, who is in his 60s. “I didn’t really enjoy my sexuality until I met Michael,” she said recently. As a young person, she had been terrified of sex: For her, as for Bea, if you got pregnant, you got married. This cudgel of respectability inhibited sexual pleasure far into her adulthood. “Shame blew both of my marriages,” she told me. “But Michael is in a different generation with a whole different approach to sex. And I’m going along with it … but it’s been a journey.”

For some of the women I met in Phoenix, it would take decades to unlearn a fear of sex and birth—to claim pleasure, to claim joy, and to hold fast to that which, for them, had finally become life affirming and empowering.

Today, in a U.S. where Roe v. Wade has been overturned, stories about women making difficult choices when faced with unwanted pregnancy are becoming ever-present. Reporting from abortion ban states such as Texas, Florida, and Alabama often describes medical emergencies related to miscarriages, such as Joanne’s, as exceptional examples of the need to strengthen access to reproductive health procedures.

But after my conversations about reproductive health in Arizona, I’ve realized how overemphasizing these emergencies (some are true horror stories) generates a false understanding that simply making abortion legal again will guarantee reproductive justice.

Making abortion legal is vital—but as my friends in Phoenix know and shared with me, it’s never been a guarantee. What struck me most about Bea’s and Joanne’s stories was the bland tone they used to tell them, how unremarkable they felt their stories of being denied reproductive care were.

In contrast, my anger about the instability and retraction of reproductive justice in the U.S. revealed a deeply rooted expectation about my bodily autonomy, about the right to decide what happens to my body and when. As someone who grew up in the 1990s and 2000s, mine was an expectation rooted in the legal right to abortion.

Over the years I have known my friends in the retirement community, they have shared the stories that have shaped their lives: sexual harassment in the workforce, gender discrimination in universities, marriages that hampered their ability to flourish. Their lack of access to reproductive care was similarly mundane: They always knew their lives and health might turn on the whims or beliefs of a powerful and distant arbiter.

I know these stories, too, and have at times found myself in similar situations. And yet when faced with obvious examples of gender and sexual discrimination, I expect recourse, look for protection, or feel outrage; my friends in Phoenix do not. They were too busy child-rearing and working to benefit from the expansion of women’s financial freedoms and the Second and Third Waves of feminism that I took for granted.

Bea, Alice, and Joanne had wanted to take a break from political work. But they are planning their return because of the onslaught against abortion access in Arizona. They know the consequences, they tell me: Gather support and fight, fight, fight.