The Rise of Aunties in Pakistani Politics

Naz (a pseudonym) clutches my hand tightly as we navigate our way through the swarms of people. We have traveled for three and half hours from Lahore to Islamabad by car, but by the time we arrive in the Pakistani capital, major roads have been cordoned off. We have no choice but to walk the rest of the way to the women’s protest site. Determinedly, Naz, who I refer to as Aunty, uses the long end of her pale green headscarf to cover her nose and mouth. The rest of us in the group follow suit, using our stoles and dupattas to prevent us from inhaling fumes and dust along the way.

I think back to when I first met Naz Aunty and her friends. We’d become acquainted during daily walks in a neighborhood park in Lahore, where our passing greetings and friendly nods had gradually evolved into deeper conversations about domestic life, children, and the pandemic. At that time, I never imagined we would find ourselves traveling across cities and participating in a political rally together a few months down the line. Yet here we are.

Naz Aunty, a stay-at-home mother since her marriage over three decades ago, is in her late 50s with three adult children. Like many middle-class, nonworking women of her generation, she told me early on that she disapproved of the politically active younger generation. She was dismayed that her own daughters support international women’s movements such as #MeToo and the annual Aurat March, a women’s march held in Pakistan for women’s freedom of movement, protection from sexual harassment, and other political and legal rights.

“I am against these things!” Naz Aunty told me then. “It makes life difficult for our daughters after marriage. My daughters make fun of me and say I am so old-fashioned.”

After walking for about half an hour, we pass through the security scanners at Parade Ground, a central gathering place in Islamabad. The congregation area is packed with throngs of women dressed in red and green, waving party flags and singing along to festive music.

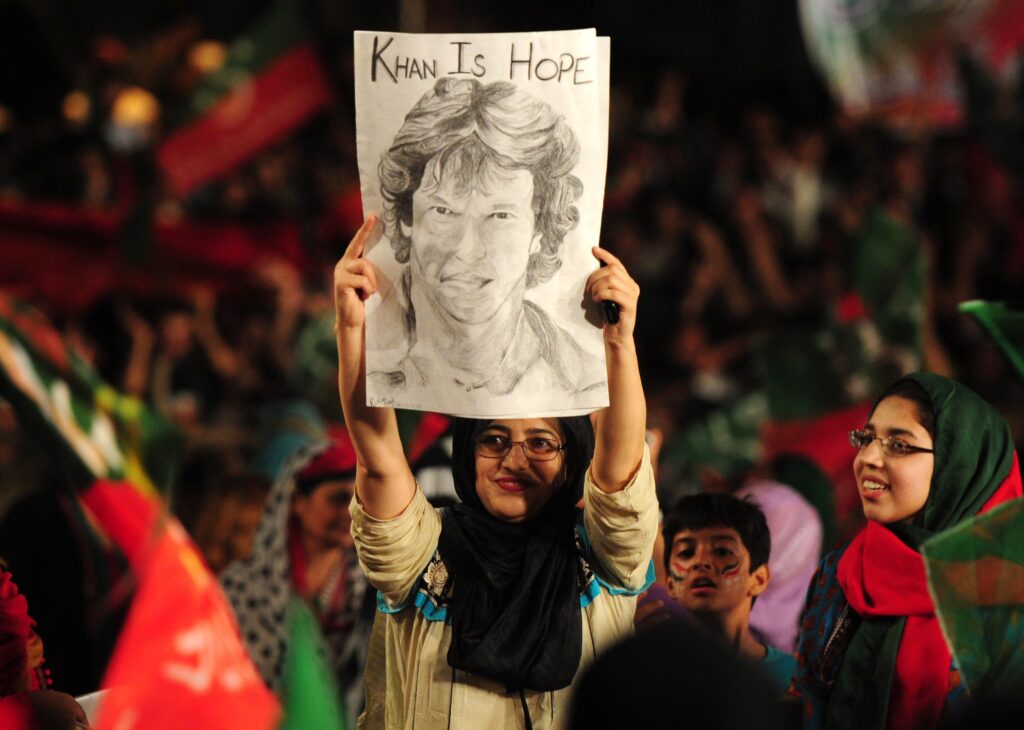

These women, like Naz Aunty, are all supporters of Prime Minister Imran Khan. Khan offers them a different vision of politics, where women with more traditional Islamic family values feel welcomed. They’ve gathered here to protest an anticipated vote of no-confidence—an event that would come to pass a few weeks later in April 2022, removing Khan from office. But in March, the atmosphere buzzes with excitement and anticipation as Khan descends from a helicopter. He makes his way to the stage—located next to the women’s enclosure—for his speech.

Fixing the pale green scarf over her streaked blond hair, Naz Aunty turns to me and says ecstatically, “Dekho aurton ki jagah sab se agay hai!” (Look, women are right at the front!)

PAKISTANI WOMEN IN POLITICS

Going to do fieldwork as an anthropologist, I had planned to follow the secular women’s movement in urban Pakistan and explore how women lobby for access to public spaces. But I started noticing that middle-class, conservative women like Naz Aunty were increasingly participating in protests and rallies as supporters of Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party. Since 2013, Khan’s populist movement has relied heavily on street protests, political rallies, and intercity-long marches—with women forming an integral part of his support base.

This intrigued me: How had Khan’s populism inspired Naz Aunty, and women like her, to become politically engaged for the first time in their lives?

Despite limited political opportunities for Pakistani women, their participation in politics is not unheard of. Rather, prior and up to the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan in 1947, women in British India participated actively in anti-colonial and independence movements. In the decades following independence, women’s rights activists remained at the forefront of political action in Pakistan, lobbying to overturn draconian laws that discriminated against women. In 1988, Pakistan became the first Muslim-majority country to elect a woman as its head of state when Benazir Bhutto became prime minister.

Today the women’s rights movement in Pakistan comprises two generations of urban women. The first grew out of organizations such as the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), established in 1981 during a period of Islamization and laws discriminating against women. WAF’s work continues to inspire a younger generation of feminists such as Naz Aunty’s daughters. This generation of activists, who came of age in the post-9/11 era in the aftermath of the Global War on Terror and during the social media boom, began leading the annual Aurat March in 2018 to coincide with International Women’s Day.

Women like Naz Aunty, however, don’t fall into either category. While they are close to the first generation of activists in terms of age and experience, their political and social inclinations do not align with their counterparts. Similarly, these women do not participate in, nor actively support, their daughters’ feminist activist pursuits. Naz Aunty and her friends always took part in elections, citing it as their civic duty (and accompanied by their husbands and sons), but weren’t politically active beyond that. Instead, they spent decades in private spaces such as the household, engaging in caregiving activities with their families.

Mundane daily practices, such as taking a walk in the park, can create possibilities for deeper forms of political engagement.

Naz Aunty and her group of friends have been PTI supporters since Khan contested elections in 2013. But at first, they avoided going to protests and rallies. On one of our walks, Naz Aunty lamented, “Before my mother-in-law passed away over a year ago, I was not allowed to come to this park for walks, let alone try and make friends in the neighborhood.”

This changed during the pandemic, when public parks became safe havens for people to socialize responsibly and maintain social distancing. It also became a space where Naz Aunty realized her political potential while walking with her new friends.

KHAN’S APPEAL—AND CONTRADICTIONS

Since his rise to political prominence following his 2013 election campaign, Imran Khan has been a divisive figure in Pakistani politics. The former cricketer and philanthropist turned politician reins in his middle- and working-class followers with anti-corruption rhetoric coupled with an emphasis on Islam and piety. His public speeches celebrate Islamic values, the centrality of the family, and traditional gender roles for women.

This rhetoric contributes to his appeal for women like Naz Aunty, who find themselves represented—perhaps for the first time—in Khan’s narratives. Khan’s followers appreciate how his politics seem to occupy a middle space between the contemporary women’s movements, which they see as too “Western,” and the stricter religious dictates of the Islamic clergy who limit women’s roles and mobility.

When Khan communicates that Islam promises women more rights than other faiths and that pious woman are a pillar of society, his followers see it as exalting their position in society and giving them their due credit as mothers—a role they have worked hard to prove themselves in. Khan holds his own mother in high esteem: The hospital he founded that caters to thousands of underprivileged cancer patients across the country is named after his late mother.

This sense of validation was reflected in Naz Aunty’s comment about women being given preferential treatment at the Khan rally: “Look, women are right at the front!” I saw it as a cheeky rebuttal to her daughters, who frequently claim that women do not have safe access to public spaces in Pakistan. However, her statement also signaled a sense of hope that there was a public space where Naz Aunty felt accepted and included.

The women’s movement, however, has vocally criticized Khan’s populist agenda. Women’s rights activists across generations see his messaging about women’s piety as misogynistic. They also cite his lack of support for actual structural changes for women and gender minorities in Pakistan. Khan did not, for example, endorse the women’s protection bill in 2006, which amended a set of draconian laws known as the Hudood Ordinances that criminalized women in cases of adultery and rape. While Khan’s populist politics may have offered more visibility to urban women in the public eye and mainstream media, women’s rights activists are skeptical of how this translates to the protection of women’s rights, status, and safety in real terms in Pakistan.

AUNTIES IN WAITING

Naz Aunty and her neighbors are not well versed in feminist theory or politics. They don’t consider themselves feminists or even activists. However, like their daughters, they also have political desires and aspirations—even if their goals don’t align.

As an anthropologist, I observed that Naz Aunty’s political journey reveals a broader insight about social change: how mundane daily practices, such as taking a walk in the park, can create possibilities for deeper forms of political engagement.

Her story also shows how ordinary Pakistani women, who have spent decades of their life “in waiting,” are finding spaces of political potential in their everyday lives. By supporting a populist movement with a group of like-minded women, Naz Aunty is carving out a space for herself, without having to appease her elders or children.

Naz Aunty’s political leanings and practices are not isolated but are part of a global trend of women’s participation in populist movements. Former U.S. President Donald Trump, who Khan is often likened to, garnered similar support in 2016 from significant numbers of women (though this backing has declined recently).

For conservative women in Pakistan and beyond, such populist movements create a sense of hope and political possibility. Despite the contradictions and the lack of real structural changes for women offered by Khan, his movement remains popular because of how he includes women such as Naz Aunty in the public sphere—on their own terms.