On the Tracks to Translating Indigenous Knowledge

OUTSIDERS PREPARE TO VISIT INSIDERS

Next year, a team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers will travel 27 hours by train from Toronto, Canada, to Lac Seul First Nation in the northwestern part of Ontario to engage with Knowledge Keepers. For two years, they have been meeting over Zoom as part of a seven-member Teaching Circle.

Imagine joining the team as they journey from Toronto’s Union Station. They will leave behind a vast urban world of more than 6 million people as they savor the last stretches of the lush Carolinian forest.

The mission of the Teaching Circle, envisioned by Lac Seul First Nation co-author George Kenny, is to articulate a worldview held by Indigenous cultural Insiders. Insiders are people like George who practice the worldview called Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin (pronounced Ah-nish-in-ah-bay-esh-shi-kay-win), which Outsiders—such as many anthropologists—tend to define as “animism.” The term Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin encompasses practices that establish a relationship between places and people; these reflect a belief in souls, spirits, and the existence of human souls through eternity. Since mountains, rivers, land, plants, and trees are animate, all of these have souls.

In traveling, team members will not only cross physical landscapes. They will also achieve a deeper understanding of that parallel world inherent in the knowledge Lac Seul Elders hold. This knowledge has survived and been adapted amid settler-colonial efforts to manage Indigenous communities and create a viable Canadian state out of a patchwork quilt of settler communities and Indigenous peoples.

But first, team members will go within to prepare for their destination.

The team’s Outsiders will engage with Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin on its own terms. Through direct experience, Outsiders will come to see the relevance and significance of what Lac Seul community members have to share. As part of this journey, the circle will consider how Insider worldviews can be translated for Outsiders, listening in a way few Outsiders have done.

ASKING “THE GODDAMN INDIAN”

In March 2021, I (co-author Alicia) met with George and his son, Mike, over Zoom. George told me he’d chosen me to work with since I’d trained as a field archaeologist with the late C.S. “Paddy” Reid, formerly the Ontario Regional Archaeologist in Kenora, northwestern Ontario, and as an archaeologist and ethnohistorian with the late Bruce G. Trigger at McGill University.

George said he liked the way Paddy and Bruce explained complex ideas clearly, were rigorous, and demonstrated strong ethical codes of conduct in working with Insiders. Bruce had worked with the Huron-Wendat and Paddy with Algonquian-speaking peoples (Cree, Ojibwa, and Oji-Cree). George wanted me to help him explain his ideas to Outsiders.

Most Outsiders never bothered to “ask the goddamn Indian,” he said. He wanted Insiders to be heard on their own terms.

To do so George subsequently enlarged his Teaching Circle to include other Outsider members. He invited them to come to Lac Seul to understand the worldview that frames, structures, and communicates knowledge.

The Teaching Circle is cast wide. It includes a biologist, medic, intellectual historian, and experts in Indigenous literature, sports studies, and jurisprudence. Members will embark on a train ride next year for Lac Seul. Zoom will be replaced by in-person conversations.

PRESERVING TRADITIONS AMID COLONIALISM

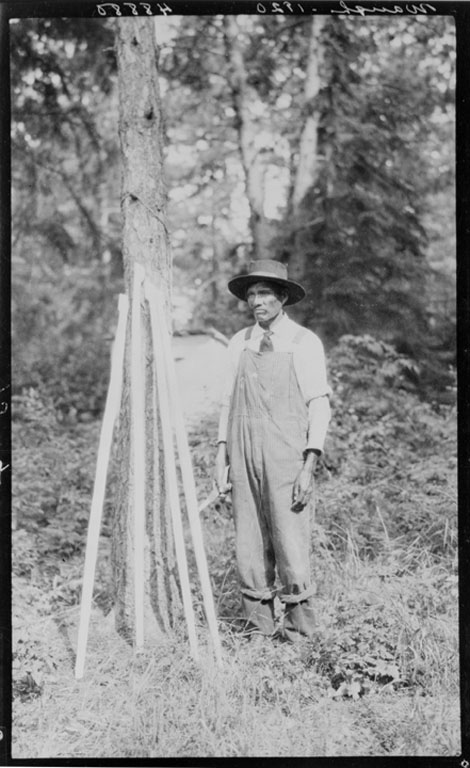

The team’s destination, Obishikokaang (Lac Seul), known as the place “where the white pines grow,” is the territory of the Anishinaabeg (called Ojibway by Outsiders who often label them as “hunter-gatherers”). With an on-reserve population of 934, people manage their wild rice, berry-pick, harvest plant medicines, and hunt local game. Some families originate from farther north, where Cree and Ojibway languages comingle. They speak a dialect of Oji-Cree.

Obishikokaang comprises the communities of Frenchman’s Head, Whitefish Bay, and Kejick Bay. Construction of hydroelectric dams in the 1930s flooded a fourth community called Canoe River and destroyed burial grounds, homes, berry patches, fields, and pictograph sites. This increased tensions with Outsiders.

For knowledge of the area’s history, Outsider researchers naturally draw on ethnographic, historic, and archaeological data—but their knowledge of the details is patchy. Typically, they rely on King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 as evidence of British occupation. This decree acknowledged First Nations as sovereign entities and affirmed their land titles. Outsider researchers also rely on Peter Pond’s map of 1785, where Lac Seul first appears as “Lake Alone.” Pond, the first White person to map from the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay westward to the Rocky Mountains and northward to the Arctic, opened this region to Outsiders—many of whom exploited the fur trade until logging and mining became the prominent industries.

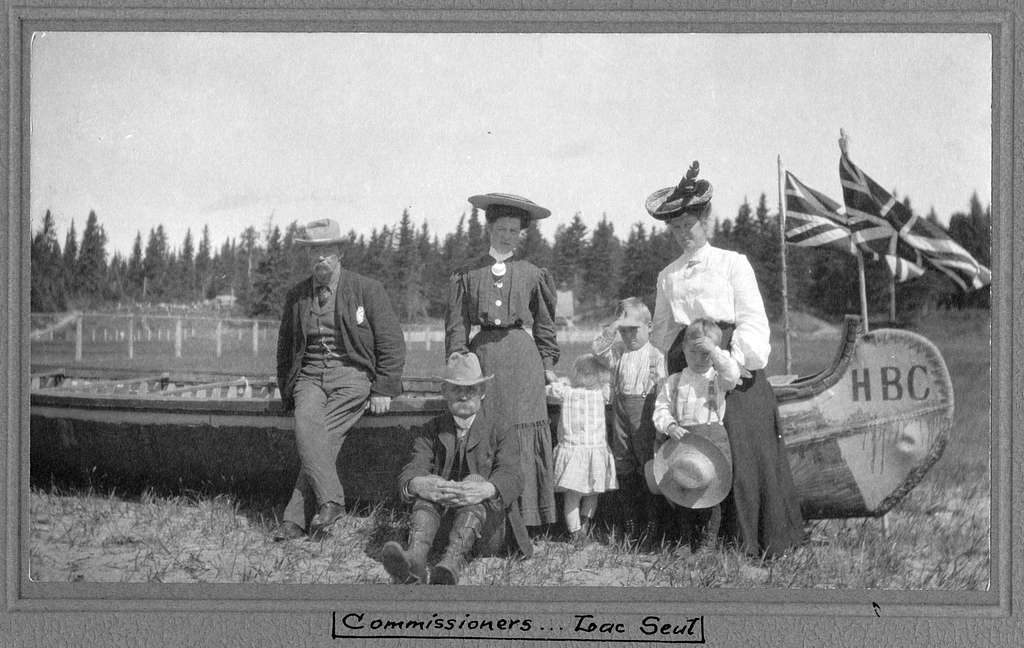

Starting in the 1820s, British officials began legislating to create a viable administrative system, in part to defend the area against U.S. incursions. For the Lac Seul First Nation, the community was swept into the administrative arrangements that accompanied the birth of the Canadian Confederation in 1867. On June 9, 1874, Grand Chief John Crow Marten (a.k.a. John Cromarty), my (George’s) great-grandfather and other chiefs signed Treaty No. 3. [1] [1] In Anishinaabemowin, his name was Andeggwabbishhazhi, which roughly translates as Crow Marten Who Sits on the Land. The Nation understood the Treaty as existing between the U.K.’s Queen and their People for all time.

Fur trade declined, and Outsiders dominated. Armed by a sense of inevitable “progress,” Outsiders brandished formidable legal and cultural weapons: Their interpretation of the Indian Act of 1876 delegitimized First Nations by depriving them of a sense of self-worth. Many spiritual ceremonies were banned. Nevertheless, my (George’s) father, an apprentice shaman, told me that ceremonies such as the Vision Quest and the Feast of the Dead continued to be practiced through the 1870s and into the early 1930s.

John Kenny Keesic, my father, was an apprentice shaman to Allen “Amoo” Angeconeb, one of many medicine people (Anishinaabeg Mushkikiewak) who were teachers (Kekinoamaged). (“Shaman” is an Outsider imposition.) My father taught me aspects of Ahnishinahbayeshshishikaywin from my birth until close to the time of his passing in 1980.

From the 1870s into the ensuing decades, White settler-colonial supremacy inspired the Indian residential school system, land planning, the registered trapline systems for Indigenous trappers, and the Scoop (trafficking of Indigenous children). By the 1920s, the country celebrated First Nations’ hinterlands as Canadian “wilderness” in landscape paintings of the Group of Seven artists. Though these legal and cultural efforts relentlessly chiseled away at the dignity and sovereignty of people in Obishikokaang, the community continued to preserve traditions and speak for themselves alone.

JOURNEYING TO LAC SEUL FIRST NATION

VIA Rail’s Number 1, the “Canadian,” running between Toronto and Vancouver, British Columbia, is touted as “a great way to see the country.” When the team boards, they will notice how Toronto’s imposing Union Station screams “Empire.” It sits squarely on the Toronto Purchase of 1787, lands obtained by Outsiders from the Mississauga Insiders.

On its northwestern route, the Number 1 crosses a landscape of rivers, lakes, and swamps, with oceans of pine, poplar, and birch forests. Often referred to as “cottage country,” that Anglophone settler-Canadian term for small wooden cabins on “pristine” lakes erases millennia of Indigenous history. The team will find itself reflecting on this obliteration while whirring past wooden docks with red-painted canoes, the ever-present loon, and people fishing, canoeing, and hanging out in small boats.

The train’s route provides an illusory plushness of trees. Yet the trees hide the region’s industrial past, reflected by the persistent smattering of logging camps, mines, and tailings also visible. The forests also hide the many highways, those long gray snakes connecting networks of unpaved roads used by logging trucks and linking small communities, settler and First Nations alike.

The train’s 15-minute halt at Sudbury Junction will serve as a reminder of Canada’s real muscle. Sudbury was nicknamed “nickel capital” of a world that had needed bullets during WWI and WWII.

Fifteen hours out from Union Station, the train will pass through Oba, the closest train station to the former railway town of Marathon, located adjacent to unceded Indigenous territory, the Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, and Pukaskwa National Park, one of Ontario’s six national parks.

In due time, the team will disembark at Sioux Lookout, their final train destination. They will see the Front Street train station and airport, which currently serve as the travel hub for many of the 77 First Nations that constitute Grand Council Treaty No. 3 and James Bay Treaty No. 9.

A mere 40 kilometers down a paved road lies Lac Seul First Nation. The team will stack their bags in the pickup of George’s nephew, Jesse, and turn from the tracks receding to the east and stretching out to the west.

CEREMONIAL WITNESSES, LINEAGE GUARDIANS, AND WALKING IN TWO WORLDS

Teaching Circle members are prepared. For two years, George has generously shared aspects of Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin with them. His descriptive storytelling of the solar system, a core component of the Insider worldview, revealed sacred locations Insiders see as integral to their present, past, and future spaces.

Among circle members, George explained the meanings of pictographs on the cliff face of Route Lake created by his father, John. Others had painted on the cliffs prior to his father. The pictographs on the vertical cliff faces remain as mute witnesses, he said, to Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin, or ceremonial practice—places where the physical and nonphysical worlds meet.

Though laws prohibited medicine people from practicing Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin and missionaries endeavored to convert Anishinaabeg people, John had participated in a meaningful transfer of knowledge from Amoo, which in turn, was shared with George. Amoo and other medicine people had hidden their equipment away.

For me (George), the pictographs are neither “art” nor “rock art,” for such categories do not exist in Ahnishinahbayeshshikaywin. Nor are they “symbols,” as everything is interconnected—nothing is separate (individual). Though variations in practices exist among the 77 Northern Ontario First Nations, the world is seen as a single system.

I taught the Teaching Circle my father’s recipe used for pictograph creation and provided the instructions on how to make it. Despite the 1876 Indian Act, our community’s medicine people have preserved their knowledge: It is themselves.

I was born in April 1952. Around the age of 5 or 6, I was apprehended and sent to faraway Shingwauk Indian Residential School near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. I escaped and ran away, riding the rails. At age 11, labeled “a flight risk,” I was sent to Pelican Lake IRS near Sioux Lookout.

Over time, upward of 150,000 children were enrolled in the assimilationist residential schools. Later the government removed 20,000 Indigenous children from their homes in what was called the ’60s Scoop and placed them in non-Indigenous households with a similar goal of assimilation. I finished my secondary schooling at Queen Elizabeth High School in Sioux Lookout.

By reflecting on this history, the circle’s Outsiders recognize that George and others in his community have been the authentic guardians of their lineage and of their spaces on the landscape, with an unsurpassed connection to the Earth’s biodiversity in the region. In the process, they have served humanity through their sustainable use of biodiversity for generations, pro bono, often at great peril.

My (co-author Mike’s) role in this work is that of the unifier. That is quite close to the role I also played in my hockey career. As a Toronto-born Anishinaabe-Estonian doctoral student and a son of George, the theme of walking in two worlds, once a space of internalized unbelonging, has since revealed countless avenues of self-discovery and opportunities to share all that I have come to learn.

TRANSLATING INSIDER WORLDVIEWS

Once in Lac Seul, the Teaching Circle, completed by the presence of the Lac Seul leadership, Elders, and younger community members, will attempt to combine two strands of thinking: the Insider Elders’ polymath and holistic perspective, expounded through “storytelling,” and the Outsider methods of field observation and the quantitative and qualitative methods of classifying flora, fauna, weather, and physical landscapes. They will help translate “animist” Insider worldviews for Outsiders.

For Insiders, the aim is to change the mindsets of anthropologists, researchers, and the public. Insiders have much to say, and some of it will never be easy listening for Outsiders. Tensions are all too prevalent, and the resulting loss of knowledge just deepens a shared predicament.

For these Outsiders, they’ll learn to read landscapes differently, listen to the “goddamn Indian”—and act accordingly.