The Uninvited Invitados

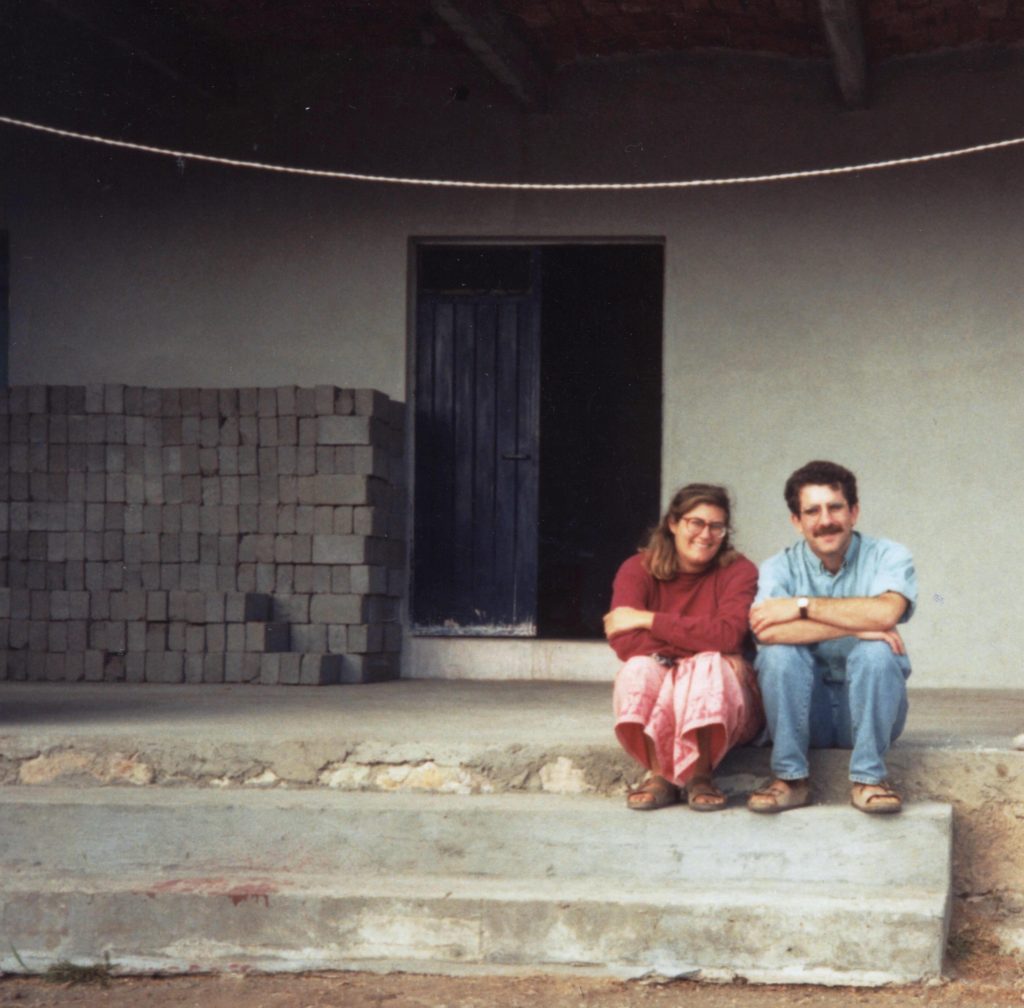

Anthropological fieldwork is often described in terms that can seem almost heroic. My introduction was a bit more prosaic. It started with a pounding on the door at 5 o’clock in the morning. It was September 1992, and my wife Maria and I had recently arrived in Santa Ana del Valle, Mexico—a small, agrarian, Zapotec-speaking community of about 2,000 in the state of Oaxaca.

Don Mauro, our patron and sponsor during our year there, was knocking. (The term don serves as an honorific title meaning “sir.”) He had given us accommodation in a home he had built for his son, who had moved north to the United States in the 1980s. We were just starting to settle in when Don Mauro arrived early that morning and impatiently called for us to join him. We quickly dressed, had coffee, and set off with him for our introduction to village life: a wedding that would be our first lesson in local customs and the many rituals that punctuated life in Santa Ana.

Don Mauro hurried us down the hill and asked us what gift we had for the young couple. We were empty-handed. He detoured into a tienda (market) where he directed us to buy a few bottles of mescal and two cartons of American cigarettes. We did as we were told.

Weddings are a big deal in rural Oaxaca. They require significant expenditures of time and money, with a church ceremony, a civil ceremony, and a party for several hundred guests who expect to be entertained. These events occur over several days, and they are critical to the cooperation and reciprocity that defines social life. Everyone celebrates and contributes gifts—of cash, time, or goods—and each gift, no matter the amount or value, is entered into the newlywed’s guelaguetza (gift) book. The book becomes a history of the family’s giving and receiving over time.

As we entered the compound, the guests silently stared at us. Unfazed by the curious crowd, Don Mauro guided us into a large room where we put a few pesos on a table along with our gifts. We had never met the maridos (the couple being married) or their families, but there we were. Eventually, taking our cue from the people around us, we made a short speech to everyone in the room and acknowledged the family’s kindness with a few words of praise. We watched as one member of the groom’s family added our names to the gift book. With that gesture, we were intimately connected through the gift—and if we followed local custom, we could expect a returned favor at a later date.

Don Mauro ushered us from room to room. There was a wide table filled with invitados (guests). They included friends and family from around the village who ranged in age from their late teens to their late 60s, all dressed for a party in their very best clothes, hats, shawls, and polished shoes. Among the guests were farmers, artisans, day laborers, and returned migrants. They spoke Spanish and Zapotec and occasionally we heard a little English as returned migrants shared their experiences. The most important guests sat around the main table. On one side were the men. Don Mauro moved to sit in the center. On the other side of the table, the women sat across from their husbands.

Don Mauro offered us a bench at the head of the table. He may not have realized it, but it was the perfect anthropological place. We were sitting alone, not with the men or the women but at the head of the table and separated from everyone else. It made sense: With a few exceptions, no one had met us yet or understood why we were in the village.

As we sat there, smiling and trying to learn a few names, the idea of liminality raced through my mind. Liminal space is an important idea in ethnographic study. The term comes from the Latin word limen (threshold), and it describes those ambiguous spaces that exist as people transition between stages in life. For example, a child goes through a liminal phase as he or she moves into adulthood. Sitting at the end of the table, we had entered an early stage of our own transition into the life of Santa Ana—we were not yet friends, but neither were we complete foreigners. Unknown to nearly the entire village, we were related to no one but associated with Don Mauro and his family. We weren’t tourists but we were gringos, and there we sat at the end of the dining table with neither the men nor the women.

Breakfast was part of the wedding. More than a meal to start the day, it was a moment to sit with friends, tell stories, and celebrate. To this day, I don’t know if Don Mauro had told anyone we were coming; people seemed surprised we were there. My hunch is that he arrived at the wedding early, told a few people he had a surprise, and returned to show off his gringos. He was beaming as villagers asked him why we were in town. Others wanted to know if we knew the newlyweds, and a few even asked if we were related to the family and from Santa Monica, California. (Many of the migrants from Santa Ana were destined for Santa Monica, California, where they would settle with friends and relatives.)

The food arrived, which interrupted the questions. Our first dish was a bowl of chocolate atole—a blend of masa (corn dough), sugar, water, cinnamon, and chocolate—served warm with sweet bread. The mixture is beaten to create stiff foam that sits on top of the warm liquid and is eaten with a small wooden paddle.

Guests offered us advice on how best to consume our bowls of atole using a combination of Spanish and gestures that mimicked scooping with the paddle. It was delicious, and once we had quickly finished, the bowls were whisked away.

The next course was higaditos (literally, “little livers”), a soup that combines chicken livers, eggs, and vegetables in a spicy stock. The mother of the groom placed heaping bowls of it in front of us. The soup smelled wonderful, like something from my grandmother’s kitchen. I longed for a bowl of her rich, Russian-style chicken soup and a setting that was familiar to us. But my attention snapped back to the village as the cook set down a stack of handmade corn tortillas and small plates piled with salt and sliced limes. It all looked delicious, but there was something missing.

I looked at my wife, and she glanced back at me. There were no utensils. How were we going to eat our soup?

A young woman sitting next to us saw our confusion and quickly announced, in Spanish, “Get the gringos some spoons!”

A second young man jokingly asked, “Don’t you know how to use tortillas?”

Before we could say anything, a woman left to find spoons. We heard her rummaging around, and then she returned polishing two spoons with a dry cloth, holding each to the light to check for dirt. It was quite clear that spoons were not necessary—but we were going to get them, whether we wanted them or not.

I decided to use the opportunity to connect with our new neighbors. “How should we eat our higaditos?” I asked.

That day, so early in our fieldwork, we had lots of teachers to help us. Everyone wanted to show us the right way to use our tortillas. The moment was about more than simply eating. It was a chance for everyone to show us, the gringo anthropologists, that we didn’t know a whole lot about life in the village.

Eating soup without a spoon was a simple skill. As time went on, we learned how to fold our tortillas in order to eat and enjoy our soup, though we did spill a lot. And as we were invited to more events—weddings, baptisms, funerals—we knew what to do when food showed up. We even had the opportunity to help with the preparations.

Our identities weren’t fixed around anthropology, and we were certainly not heroes, but we went from gringos and strangers to something that was at least a little more familiar. We became Mauro’s gringos. It is an identity that more than 20 years later continues to define us in the village.