When Harmony Silences Resistance

Since Samuel (a pseudonym) started marching in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests, the harmony in his family has been shattered. Hong Kong has been in chaos since June, when a controversial extradition bill, plus alarm over mainland China’s increasing interference in the city’s autonomy, sparked mass demonstrations that ignited into violence, police brutality, and vandalism.

Samuel, a recent college graduate, has been on the frontlines of many of these demonstrations. “I just want to make the society a better place,” he told me. “[But my parents] think it is naive to believe that one could change the society. All they care about is stability and order.”

Samuel’s family disapproves of his participation in the protests. They think society cannot be changed and that the city should return to a state of harmony. When he tries to explain his views, they argue with him. So, to try to restore family harmony, he has started keeping quiet.

Harmony is a central ideal in Chinese culture, and the word has echoed like a drumbeat throughout the protests. At a press conference in August, Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, announced, “We need to object to violence and maintain the rule of law. … When this all calms down, we will start to have sincere dialogues and rebuild harmony.”

But does harmony come at a cost?

American anthropologist Laura Nader coined the term “coercive harmony” to describe a strategy for controlling people through forced compromise and consensus. Everyone desires to live in a peaceful and harmonious society. But that desire can be manipulated to silence citizens in the streets, in the halls of government, in the workplace, and even—as Samuel discovered—at the dinner table.

Replacing the pursuit of justice with the pursuit of harmony can be a technique for subduing people.

As a Hong Konger, a participant in the pro-democracy rallies, and an anthropologist who studies Hong Kong’s society, I have been shocked by the recent acts of egregious violence and flagrant police brutality. Police have viciously beaten protesters and fired live bullets, rubber bullets, tear gas, and pepper spray at crowds. Protesters have thrown Molotov cocktails and bricks at police. More than 1,700 people have been injured, two are reported dead, and around 4,490 have been arrested.

Yet what shocks me even more is the Hong Kong government’s attempts to justify excessive force and draconian law to restore a false sense of harmony.

Media attention about the Hong Kong protests focuses on this overt violence. But these acts can hide a more insidious form of violence—the brutality of a coercive harmony, which governments around the world have used to quell social movements and suppress people’s voices under the guise of peacekeeping.

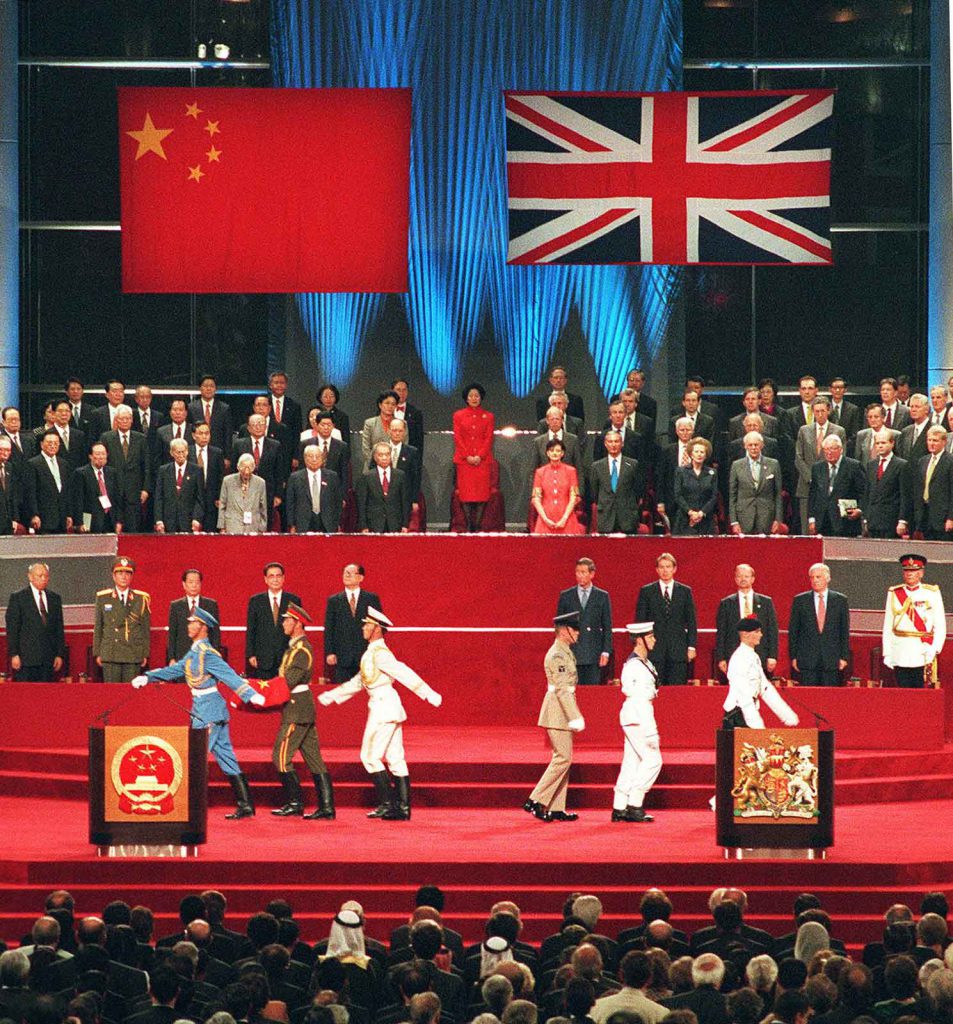

Tensions in Hong Kong were smoldering long before the protests ignited. Since the handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China in 1997, China has operated under a principle of “one country, two systems,” in which Hong Kong maintains its own legal systems and law enforcement.

Mainland China’s Communist government, headquartered in Beijing, had promised that Hong Kong’s chief executive (similar to a governor) would eventually be elected by universal suffrage. But that hasn’t happened.

Instead, because of gerrymandering and a skewed election system, the chief executive and Legislative Council are elected largely by a committee of special-interest groups—the majority of which are pro-Beijing—rather than by ordinary Hong Kong voters.

In addition, China is increasingly interfering with Hong Kong’s domestic affairs. In recent years, the Beijing government had six elected politicians removed from Hong Kong’s legislature for making critical statements about China in their oaths of office. Booksellers who publish banned books critiquing China have been abducted.

In April, Hong Kong’s legislature began debating a bill that would have allowed criminal suspects in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China. Hong Kongers distrust the opaque and arbitrary legal system of mainland China, and for good reason. Chinese President Xi Jinping has denounced judicial independence and called for creating lawyers who are “loyal to the party.” Chinese police arrested around 300 human rights lawyers and advocates, and allegedly tortured at least one of them. China also executes more people than any other country, mostly in secret, according to Amnesty International.

Many Hong Kongers saw the extradition bill as a form of legalized kidnapping that would allow Beijing to silence its critics.

On June 9, more than a million people marched through Hong Kong in a peaceful protest. In a subsequent rally, a small group of protesters threw bricks and umbrellas at police, who responded by firing tear gas at people and beating them with batons. Chief Executive Lam tried to restore calm, saying at a press conference, “We may disagree, but we’re still in harmony.”

The clashes kindled a firestorm of protests that drew as many as 2 million people. Then on July 21–22, heinous attacks changed the protest indefinitely. A mob of people in white shirts wielding wooden rods stormed into a metro station and violently assaulted protesters, journalists, and ordinary commuters. The typically spotless train station floor was splattered red with blood.

“Where on earth were the police?!” a man shouted hysterically at a telescreen camera. The police turned up at the crime scene more than 30 minutes late and arrested none of the attackers, leading many people to accuse them of colluding with the mob to subdue protesters. At least 45 people were injured, and police later arrested 12 suspects for the attack, many of whom are connected with an organized crime group.

The resistance from the demonstrators has since ratcheted up, and so has the police force. Protesters have thrown petrol bombs and vandalized buildings. Police have fired tear gas, shot people at close range with pepper-spray balls and other projectiles, and savagely beaten protesters.

In October, Lam invoked the Emergency Regulations Ordinance to ban the wearing of face masks at public gatherings. The ban was overturned in November, immediately prompting mainland China’s legislative body to warn Hong Kong that it would step in to reinstate the ban if necessary. Hong Kongers fear their right to protest without repercussions is being chipped away.

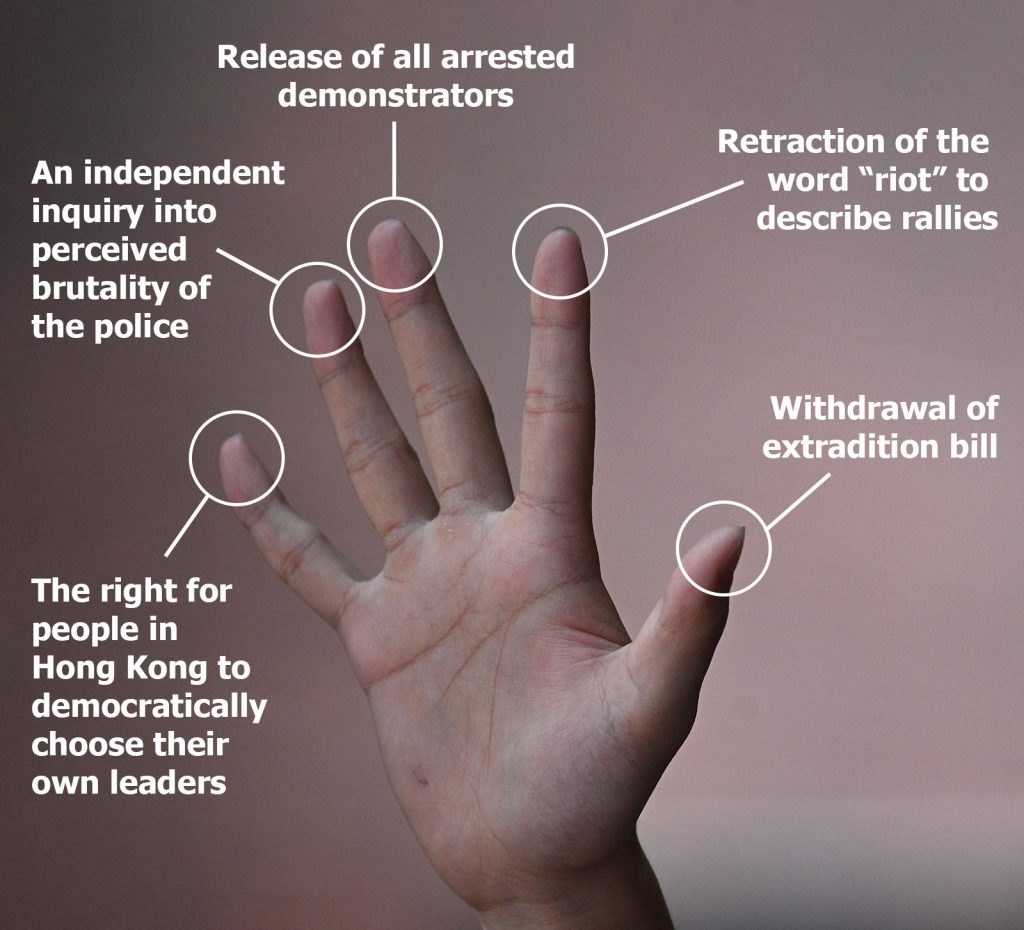

As a result, the protests are no longer just about the extradition bill. They are about justice, freedom, and the ways the government and police maintain law, order, and harmony.

At a press conference in August, Lam spoke eloquently about her determination to resolve the conflict by building harmony in society. She deflected journalists’ penetrating questions with aplomb, occasionally making emotional appeals for the restoration of order. “Are you coldhearted enough to push Hong Kong into this deep abyss that will crush us?” she asked. She said her “utmost responsibility” is “to ensure that Hong Kong remains a safe and orderly and law-abiding city.”

Harmony, in sum, is the Hong Kong government’s primary current goal. But what does it mean to live in a harmonious society? When is harmony a form of peace, and when is it a form of oppression?

In an influential 1995 lecture, legal anthropologist Nader said she started distinguishing harmony from coercive harmony while working with the mountain Zapotec of Oaxaca, Mexico. The Zapotec have a saying, “A bad agreement is better than a good fight.” This expresses a characteristic of coercive harmony: Consensus is more important than justice or efficacy. Nader theorized that Spanish colonists and missionaries introduced harmony ideology to the Zapotec to control them.

“The harmony model produces a … tranquilizing effect,” said anthropologist Laura Nader.

Nader also noticed that many in the U.S. who had been outspoken advocates for civil and environmental rights in the 1960s had become “subdued and apathetic” by the 1980s. “In about 25 years, the country had moved from central concerns with justice to concerns with efficiency, order, and harmony,” she observed. “How had this shift happened?”

Nader explained that, in the effort to suppress Vietnam War protests and civil rights marches, “harmony became a virtue,” both in the legal paradigm and in U.S. society.

In courtroom disputes, the contentious win-lose model faded out and was increasingly replaced by the mediation-arbitration process. Zero-sum settlements were deemed uncivilized, whereas so-called peaceful, win-win solutions were perceived as the marker of civilization. This new style, Nader said, was “less confrontative, ‘softer,’ less concerned with justice and root causes, and very much concerned with harmony.”

While that may seem harmless, Nader warned that the focus on harmony and “the movement against the contentious was a movement to control the disenfranchised.” People in less powerful positions are often cunningly persuaded that embracing harmony is in their best interest—even though the mediation-inspired approach tends to advantage the powerful, Nader noted.

Even worse, Nader stated, “an intolerance for conflict seeped into the culture to prevent not the causes of discord but the expression of it, and by any means to create consensus, homogeneity, [and] agreement.”

In other words, replacing the pursuit of justice with the pursuit of harmony can be a technique for subduing, silencing, and disadvantaging people. In this way, Nader observed, “the harmony model … has a tranquilizing effect.”

In Hong Kong, the government is attempting to subdue the daily resistance through appeals for stability and harmony instead of pursuing social justice for protesters, most of whom are subjected to longstanding structural exclusion and, recently, police violence.

The government is also using the goal of harmony to justify police brutality and to win unjust consensus. In doing so, they are creating what anthropologist Ann Anagnost calls “euphemized violence,” in which violence for the sake of order is made inoffensive and eventually normalized.

Meanwhile, Samuel has attempted to heal tensions in his family through dialogue. But he and his parents only end up reiterating their own opposing political views. “My mother won’t listen to me, saying that I am immature,” Samuel says. “She just tries to force me into thinking what she thinks!”

Samuel cited American psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to emphasize why he was protesting. By fulfilling his purpose to help right the wrongs of Hong Kong’s government and police, he was aiming for the pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy. Conversely, his parents were still at the lowest levels of Maslow’s pyramid, focusing on basic needs, money, and—above all—stability and order. In this regard, Samuel and his family cannot possibly communicate effectively.

“We don’t talk to each other that often anymore,” Samuel says. “We just end up in conflicts whenever we have a conversation anyway. What’s the point then? I would rather shut up. … And if we do talk, we just talk about trivial stuff.”

So, Samuel suppresses his thoughts, questions his pursuits, and silences his voice. His parents, too, remain silent. Harmony ideology does its job as argument temporarily ceases. Samuel’s home is left with some sense of calm, even though his family is plagued with unattended, simmering problems.

This version of harmony—perpetuated both by the government and society—isn’t peace. It is coercive and penetrating. It interweaves into the fabric of people’s social lives, entangling with their workplace interactions and intergenerational relationships.

As Nader suggested, the quest for harmony may also stop people from thinking about “root causes”—how and why differing perspectives form.

In her October policy address, Lam offered no political solutions to the causes of the protests. She has promised dialogues with protesters, but when she held talks with five student activists in 2014, four of them were subsequently arrested, and three were sentenced to prison. And apart from previously retracting the extradition bill, she has not granted any of the protesters’ requests.

Instead, she referenced people who have “different political views” and called for putting “aside differences” and restoring calm. But her statement glosses over people’s lived experience of inequality, social injustice, voter disenfranchisement, and police violence. These are complex social and political problems that must be investigated and addressed. They cannot be reduced to mere differences in political points of view that can be swept aside.

Lam’s underlying message seems to be to stop protesting and move on with life. And if the public’s demands aren’t met, well, “a bad agreement is better than a good fight,” as the Zapotec say.

If citizens feel argument is futile, they may eventually succumb to the harmonic whole for the sake of peace and quiet—just as Samuel did. In such circumstances, social order is restored, but it is a tense order. Society, the family, and individuals become temporarily peaceful powder kegs.

Samuel is an example of this. Sometimes his forced silence and feeling of being trapped drive him to the edge. He feels unhinged, almost off-kilter. “I would just snap, shouting madly at people who push my buttons,” he says. In the same way, the pressure that built up in Hong Kong’s society exploded into the current protests.

Can Hong Kongers—and people everywhere—reimagine a form of harmony that is more inclusive of differences?

Perhaps that harmony would be infused with caring rather than control. Resistance could be born of a sense of care that yearns to repair the havoc wreaked by Hong Kong’s government and detach from the old-style autocracy. Governance could involve a sense of care that seeks to rebuild an order without suppression, supported by a legal, social, and political infrastructure on which people could depend. Through caring, people could unlearn coercive practices and attend to the wounds of the past and present.

This caring would require people to see three things: Order revitalizes itself through change. Individuals are interdependent and must work to create a shared life in a fair, non-totalizing system. And different points of view are partially related but should not be conflated for the sake of harmony.