What Do Goats and Wars Have to Do With Glacier Loss?

For scientists, the layers of ice that make up glaciers and the study of those glaciers’ retreat reveal something about Earthly processes—they hold a record of the greenhouse gases we have poured into our skies and their contribution to global warming. As I found out during fieldwork in the Ladakh region in the Indian Himalayas, the ethnographic study of glacier recession also entails making sense of layers, but layers of a different kind: layers of politics and the human story that link glaciers to war, family, and even the keeping of goats.

I had first come to Ladakh in 2011 to understand the implications of climate change there—not its causes, which I had read much about in scientific accounts. But my focus changed when I met Tsering Tashi.

In his mid-70s, Tashi had spent a great deal of his life walking in the Himalayan mountains, plying the trade routes to Tibet and herding animals in the mountains. People called him Meme Tashi (“Grandfather Tashi”). Age had taken its toll on his body, and he could no longer do this work, but his connection with his beloved mountains was still strong. Having retired from active life, Meme Tashi spent his days spinning his prayer wheel under the sun while facing the mountain pastures of his village in the Sham area of Ladakh, a thermos of butter tea at his side, some dried apricots to chew on, and a woolen blanket on his lap.

He handed me the first piece of my ethnographic puzzle one chilly October day, when the leaves on the few trees around were turning bright orange and yellow before the onset of another long winter: “When I was young,” he recollected, “the fathers of the village would take with them bags of cold charcoal to throw on the glacier [of the village] so it would not vanish completely.”

I tried to get more information about that practice and its abandonment, feeling particularly intrigued considering the current recession of glaciers—the world’s 37 best-studied reference glaciers have lost the equivalent of 2 meters of water sliced from their surfaces since 1970. While losses for the large glaciers around Ladakh seem smaller than the global average, they are still significant. I asked about the charcoal’s purpose and how it worked to save the ice, but Meme Tashi had no answer for me. Rather, he shifted the conversation toward his life experiences, in particular to the first war with Pakistan after the Partition of India.

Meme Tashi, like other elders, was not really interested in talking about the impacts of glacier recession on his community. There were more pressing issues, such as the growing disinterest in herding animals and farming the land. While the glaciers were important to their lives, their stories were woven into stories of the war and of changing ways of life. Still in the early stages of my fieldwork, this felt very disorienting.

What did the war, the land, and the animals have to do with glaciers?

In 1947, India became an independent nation. As part of this process, the former colonial British dominions were divided into two sovereign states: India (with a Hindu majority) and Pakistan (with a Muslim majority). This abrupt Partition created sectarian violence in communities that had previously coexisted peacefully, forcing people belonging to different religious communities to migrate.

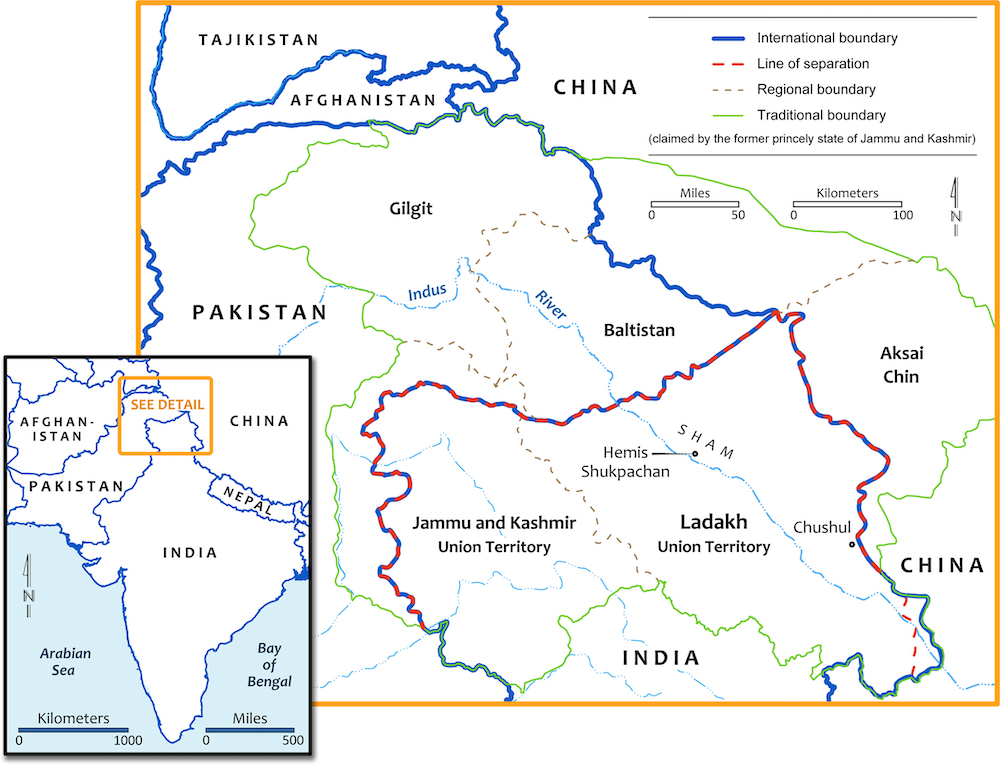

The war left its mark on the memory of the inhabitants of Sham, an area located along the Indus River in the high-altitude region of Ladakh, most of whom are Buddhists.

In 1948, for about six months, villages in Sham were occupied by Pakistan military forces. Villagers fled to the mountains. Ladakhi men were recruited into the Indian army, sometimes forcefully. Meme Tashi was one of them. He was given a gun and had to patrol the mountains surrounding his village of Hemis Shukpachan.

The work was grueling. Recruits suffered harsh beatings if they made mistakes. “There’s nothing I haven’t gone through and haven’t seen,” said Meme Tashi in an emotional tone. War-time testimonies shared by Ladakhi elders of Sham emphasize stories of killing, rape, abduction, slaughtered animals, stolen belongings, and the development of tensions between Buddhist and Muslim Ladakhis that stood in sharp contrast to the previous cordial relationships between the region’s two communities.

In the words of an elderly Ladakhi man, “When it’s war, what good can happen?”

Ladakh became an isolated border area, as its direct neighbors—China and Pakistan—were nations with whom India had hostile relationships. There would be four wars with Pakistan and, from the 1960s, constant skirmishes between troops at the border with China.

Meme Tashi worked as a porter in the army. He also continued his trading activities, traveling to Gertse in Tibet to exchange wool for various commodities. Over time, travel to places where the army of the People’s Republic of China was increasingly exerting territorial control became more regulated. Meme Tashi prided himself in managing to go clandestinely, “without a permit.”

One day in the fall of 1962, on his way back from a trading expedition, Meme Tashi stumbled upon a violent scene: one that marked his memory forever. In the area of Chushul, many dead bodies of Indian army personnel were scattered on the ground. Clothing, vessels, food, and discharged guns were strewn on the ground. Army vehicles had been destroyed and abandoned.

“This was an unimaginable scene,” shared Meme Tashi, who had happened upon a battleground of what came to be known as the Sino-Indian War.

The wars were more than just moments in the local history—they changed the destiny of Ladakh.

For Ladakhis, living in the vicinity of what became some of the most contested borders in Asia also meant new employment opportunities. The long-isolated mountain region suddenly had much more state presence. A significant proportion of Ladakhi families today have a member employed in the army or in a related support position, such as porter or commodities supplier. The region’s tourism industry has also bloomed.

These job opportunities have provided a new way for Ladakhis to pursue individual aspirations. Traditionally, Ladakhi households engage in fraternal polyandry: A system whereby brothers are wed to the same wife. This system limits population growth and prevents the region’s limited amount of arable land from being split up between family members but leaves few options for younger brothers to exert their independence. The new economic opportunities brought new ways of life.

Today, Meme Tashi laments, people don’t know these glaciers at all.

At the same time, the youth of Ladakh have lost interest in keeping livestock. Tending animals is demanding. Tsewang Dolma, a woman in her 70s, recalled her days starting at sunrise to feed the cows, after which she would trek the mountains with the goats until sunset, often in freezing temperatures. Those days left her with painfully frostbitten feet and fingers. In the summer, herders spent extended periods away from the village, staying in the summer pastures, where the cooler temperatures are better for processing milk into butter and cheese.

Today these practices and arrangements are, like many other traditional activities, falling out of use. Elders often remark how the mountain pastures now lack vitality. The dilapidated stone shelters where people would stay in the summer pastures remain a telltale sign of a changing era, as only a few elders in Sham continue these activities.

With a critical labor shortage, many Ladakhi elders find themselves forced to sell their livestock, which often means the animals will be slaughtered. This constitutes a real predicament for elders, as it conflicts with an ideal of Tibetan Buddhism: Old age is a time to prepare for a future reincarnation, and thus, one should abstain from inflicting harm on animals.

The elders I spoke to complained of the selfish indifference young people have for animals that have long helped Ladakhis survive the harsh mountain environment. They see care and farming of the land as a moral obligation and worry that people are now “abandoning the land.” Faced with shortages of water and workers, a growing number of families are leaving parts of their land uncultivated.

It was the herders who kept a close eye on the glaciers that lie at the top of the valleys near these villages—glaciers that are generally only visible by climbing to a village’s pastures.

As Meme Tashi remembers from his childhood, people would also climb to throw cold charcoal onto the glacier to preserve it. Over my years of fieldwork in Ladakh, I tried to collect information on this practice, but the details remain elusive. In neighboring Baltistan, people have a long tradition of grafting glaciers—uniting chunks of “male” and “female” ice in a ritual process meant to help the glaciers grow. This also involved charcoal, as described by Ladakhis. Whatever the details and the purpose, I heard repeatedly that “people don’t have the time today” for this custom.

Today, as Meme Tashi and other elders lament, people don’t know these glaciers at all. This body of knowledge is, like the glaciers, slowly receding.

Meme Tashi describes his local glacier, Shali Kangri, as a colossal mass of ice shaped like a cave. He recalls seeing bharal (also called blue sheep) there, enjoying the dripping water. Small glaciers like this one are rarely studied by scientists, but during my fieldwork in 2013, I organized a trek to Shali Kangri.

Meme Tashi was troubled by what he saw in the photos I’d taken: The cave was entirely gone.

Through the elders of Ladakh, I learned that for them, glacier recession is not an abstract global phenomenon but something inscribed in local processes.

Like outside scientists, most Ladakhi elders who have seen the glaciers around them change markedly within their lifetime believe that warming temperatures and human beings have something to do with it. But for them, human involvement is not limited to emissions of warming greenhouse gases. The state of a glacier cannot be disentangled from its locality, its community, and, importantly, the ethical dispositions of the people toward the animals and the lands.

As I came to understand through my conversations with elders, glacial recession is seen as part and parcel of the retribution for the wars that have taken place in Ladakh, in which the people of Sham were sometimes forced to partake. It is enmeshed in the erosion of community responsibilities and the gradual decline in agropastoralism. In other words, glacier recession cannot be disentangled from the major changes taking place in this part of the Himalayas over the last several decades or from the predicaments faced by elders.

This perspective amalgamates many things, including Buddhist ideas about the environment, local moral values, and an understanding of what should be an ethics of care for others: human and nonhuman. While animals and wars seemingly have nothing to do with glaciers, for Ladakhi elders, they are at the center of this complex puzzle of climate change.