The Hidden Resilience of “Food Desert” Neighborhoods

Even before Ashanté Reese and I reach the front gate, retired schoolteacher Alice Chandler is standing in the doorway of her brick home in Washington, D.C. She welcomes Reese, an anthropologist whom she has known for six years, with a hug and apologizes for having nothing to feed us during this spontaneous visit.

Chandler, 69 years old, is a rara avis among Americans: an adult who has lived nearly her entire life in the same house. This fact makes her stories particularly valuable to Reese, who has been studying the changing food landscape in Deanwood, a historically black neighborhood across the Anacostia River from most of the city.

When Chandler was growing up, horse-drawn wagons delivered meat, fish, and vegetables to her doorstep. The neighborhood had a milkman, as did many U.S. communities in the mid-20th century. Her mother grew vegetables in a backyard garden and made wine from the fruit of their peach tree.

Food was shared across fence lines. “Your neighbor may have tomatoes and squash in their garden,” Chandler says. “And you may have cucumbers in yours. Depending on how bountiful each one was, they would trade off.” Likewise, when people went fishing, “they would bring back enough for friends in the neighborhood. That often meant a Saturday evening fish fry at home.”

Around the corner was the Spic N Span Market, a grocery with penny candy, display cases of fresh chicken and pork chops, and an old dog who slept in the back. The owner, whom Chandler knew as “Mr. Eddie,” was a Jewish man who hired African-American cashiers and extended credit to customers short on cash. Next door was a small farm whose owner used to give fresh eggs to Chandler’s mother.

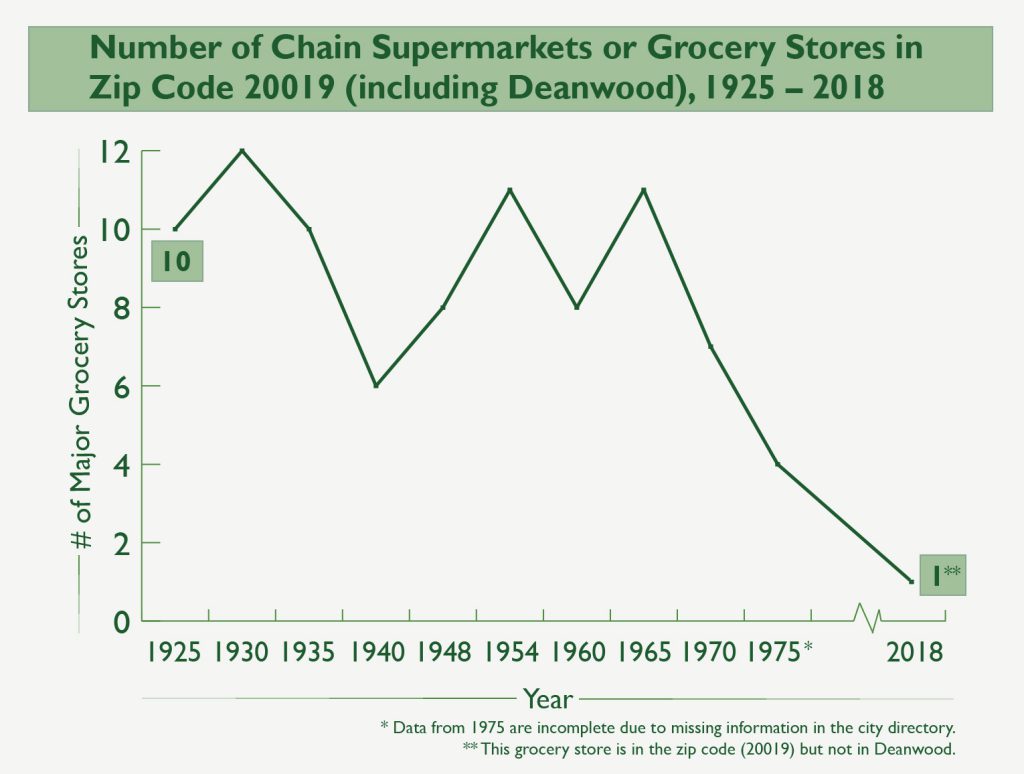

Chandler was born into this architecturally eclectic neighborhood. On the basis of oral histories found in archives, Reese mapped 11 different groceries that were open in Deanwood during its peak years, the 1930s and ’40s. African-Americans owned five. Jews, excluded by restrictive covenants from living in some other D.C. neighborhoods, owned six. For much of the mid-20th century, there was also a Safeway store.

Today there are exactly zero grocery stores. The only places for Deanwood’s 5,000 residents to buy food in their neighborhood are corner stores, abundantly stocked with beer and Beefaroni but nearly devoid of fruit, vegetables, and meat. At one of those stores, which I visited, a “Healthy Corners” sign promised fresh produce. Instead, I found two nearly empty wooden shelves sporting a few sad-looking onions, bananas, apples, and potatoes. The nearest supermarket, a Safeway, is a hilly 30-minute walk away. A city council member who visited last year found long lines, moldy strawberries, and meat that appeared to have spoiled.

The common name for neighborhoods like these is “food deserts,” which the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as areas “where people have limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable food.” According to the USDA, food deserts tend to offer sugary, fatty foods; the department also says that poor access to fruits, vegetables, and lean meats could lead to obesity and diabetes. A map produced by the nonpartisan D.C. Policy Center puts about half of Deanwood into a desert.

But Reese, an assistant professor of anthropology at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, has joined a number of scholars who are pushing back against the food desert model. She calls it a “lazy” shorthand to describe both a series of corporate decisions and a complex human ecosystem.

“Language matters,” says Reese, who explores these issues in a new book, Black Food Geographies, due out next year. Use the wrong words to describe the problem and you end up with one-dimensional solutions that don’t address the root causes of poor diets. Both the U.S. and British governments have emphasized supermarket-building as a way out of their country’s nutrition woes. Yet there’s “limited causal evidence” that this strategy improves diets, according to a 2017 report by economists from New York University, Stanford University, and the University of Chicago. They analyzed food-purchase data to understand the complex reasons why affluent Americans eat healthier than their poorer counterparts and concluded that leveling the grocery field would “reduce nutritional inequality by only 9 percent.”

Reese adds that people often inaccurately think of deserts as lifeless. “The desert metaphor [implies] there’s really nothing of value,” she says. “When we use ‘food desert,’ we don’t see the people and businesses and networks and thoughts and desires and hopes. This metaphor wipes all of that off the map.” By looking past the label, she argues, we can finally understand and address the decades of disinvestment that have depleted neighborhoods of healthy retail options—and we can finally appreciate the resilience of current residents.

How communities feed themselves has been a theme running through Reese’s life. Now 33 years old, she grew up in Porter Springs, Texas, whose population was (and is) 50, on a red-clay dirt road where everyone was family, “biological or not.” Her uncles raised goats, hogs, and poultry for slaughter, and Reese remembers her grandfather wringing chickens’ necks to process them for consumption. She and the other children picked wild blackberries, which her grandmother baked into what Reese recalls as “soulful” cobblers.

After college, in 2008, while Reese was teaching social studies and coaching track and field at an all-girls public school in Atlanta, she had a conversation with two young athletes that would inspire her later research. Reese had taken the girls to a clinic for a physical exam and was planning to cook dinner for them afterward. They went shopping together in suburban Cobb County. The girls marveled over Reese’s neighborhood store, leading her to realize that even though they lived just a few miles away, they had never seen such bounty.

That same year, after Reese had taught her students about civil disobedience, they proposed a boycott of the cafeteria to protest its scant offerings. Reese’s one condition was that no classmate went hungry. “If someone can’t bring their lunch, then someone needs to bring an extra lunch,” she remembers telling them. The students’ efforts eventually led to a meeting with a school district representative, after which the school got a salad bar.

Those stories—about the power of food to widen inequalities and to bring people together—were on Reese’s mind when she entered graduate school at American University in Washington, D.C., and began studying Deanwood. It was 2012, and Reese was interested in how the neighborhood’s food geography affected people’s diets. Her first impulse was to ask neighbors about the contents of their pantries. That’s not, however, what they wanted to talk about.

Instead, they began with history: the time when they had several grocery options, walked to shops, gardened in their yards, and bought produce from “hucksters” selling from wagons and trucks. “There were some gendered memories, too, around women and cooking, and remembering a time when mothers were home to do that,” Reese says. (Chandler, for instance, recalls how rigorously she learned to cook: “That shucking of the corn—you had to do it precisely. You had to snap the peas in a given way.”)

Throughout Reese’s interviews, “the theme of community ran through quite strongly,” she says. This was, and is, part of Deanwood’s identity. The neighborhood took shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as African-American architects, drafters, and carpenters designed and built single-family wood-frame houses on farmland once worked by slaves. It was also home to the Suburban Gardens Amusement Park, a destination for African-American families who were barred from whites-only parks. On the historical markers that dot its streets, Deanwood residents are described as “a self-reliant people.”

This self-reliance is communal, not individualistic. “One of the elders was telling me about how he didn’t remember there being homelessness in Deanwood in the past like there is now,” Reese says. “It wasn’t because people weren’t transient. It’s just that someone would always take them in.”

Shortly after Reese began her fieldwork, she attended a conference where, for the first time, she heard scholars criticize the food desert model. Their arguments, along with Reese’s Deanwood interviews, forced her to reconsider some of the assumptions she had brought into graduate school.

The food desert concept originated in Great Britain in the 1990s. According to the BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal), a public housing resident in Scotland reputedly first used the phrase, presumably to describe their surrounding neighborhood. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government adopted the term—despite warnings of thin data.

Much like his U.S. counterpart, President Bill Clinton, Blair advocated a moderate, market-driven political approach that he called the Third Way. The concept of food deserts fit neatly into his script: Incentives and public-private partnerships could “solve” the problem by helping to build groceries in depressed areas.

The metaphor found fans in the United States, too, as an alternative to blaming poor and working-class people for conditions like obesity. “Many of the debates over food and health disparities, especially if you look at the pop-culture debates, they’re so individualistic,” says Alison Alkon, a sociologist at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California. “They’re focused on ‘Why do you not have the willpower to put down the McDonald’s and go exercise?’” (Even health professionals share these biases: In a 2003 survey of U.S. physicians, 44 percent called obese people “weak-willed” and 30 percent described them as “lazy.”)

The desert metaphor challenged these stereotypes about individual behavior. “‘Food deserts’ makes it a structural issue that has to do with urban development and redlining and economic history,” Alkon says. “Obviously, it’s a step forward.”

In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama launched the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, designed to “eliminate food deserts” in part by using grants and low-interest loans to build supermarkets. The initiative was later incorporated into the 2014 Farm Bill.

But by then many academics, including Alkon, and activists were calling the metaphor inadequate and misleading. Yes, swaths of urban America have been abandoned by the supermarket industry. But that doesn’t explain the link between wealth and nutrition.

The real explanations are multilayered and complicated. They’re partly financial: Healthy food costs more (perhaps, some critics suggest, because U.S. farm policies subsidize commodity crops like corn and soy, which are used to make processed foods), and even small price differences can break the budget of a low-income family. In addition, the complications of poverty and racism—crowded housing, job discrimination, longer commutes, diminished educational opportunities, and greater overall emotional stress, to name a few—make it harder to act on public health messages.

The factors are partly geographic, too, but not just in terms of supermarkets. During her studies, Reese discovered the work of Naa Oyo A. Kwate, an associate professor of human ecology and Africana studies at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Kwate has mapped the distribution of cheap, unhealthy fast food in New York and found an overabundance in black neighborhoods. “Segregation fosters a weak retail climate and a surplus of low-wage labor, both of which make the proliferation of fast food probable,” Kwate wrote in a 2008 paper.

It’s no surprise, then, that several studies have drawn the same conclusion: Introducing a supermarket to a depressed area does little to improve people’s diets. Two food-policy scholars, Nathan Rosenberg and Nevin Cohen, argue that the real solutions lie in “upstream interventions” that address inequality: a higher minimum wage, stronger labor protections, more generous government benefits, and universal free school lunches. “There are no shortcuts to eliminating food poverty,” they wrote in a recent article in the Fordham Urban Law Journal.

On the afternoon that we visit Deanwood, Reese cuts an elegant, fluorescent figure: lime-green nail polish, blue lipstick, and red-highlighted Marley twists piled into a bun. Because the neighborhood has so few restaurants, we first meet for lunch six miles away, near the Catholic University of America. Over shrimp and grits, she tells me about her fieldwork.

While interviewing residents, Reese says, she heard a consistent racial critique. “No matter what age, [they] felt that Deanwood doesn’t have as many options because it is predominantly black,” she says. “Almost everyone articulated that.”

She also found that Deanwood’s residents talked about how they continue to eat well by working together. Reese tells me about a community garden at a public housing complex just outside the neighborhood’s boundaries that produced vegetables such as kale, eggplant, and peppers. “They’re growing in these six raised beds on city land, which they may or may not have permission to do,” she says. Unlike many other such gardens, this one didn’t have individual plots. “There was no lock on the gate. People could come in and take whatever they wanted. … There was one man who would use stuff from the garden to make big pots of soup at the end of the month, when people’s money was low, and just share it.”

Other ways people discussed self-reliance were more mundane. They patronized the one black-owned corner store in Deanwood that sold deli meats, canned beans, and some fresh produce. They organized ride shares, especially for elders, to supermarkets outside their neighborhood. They turned old automobiles into unlicensed cabs, which they parked outside the Safeway to spare shoppers a 30-minute walk with heavy bags. (Not many taxis served the area.)

Such self-reliant solutions often become invisible in discussions of food deserts. Semantically, the word “desert” is loaded; it’s often paired with “barren” or “wasteland.” One study from Australia noted that desert dwellers are often viewed as “marginalized” people who live off subsidies from the mainstream.

In her research, Reese met scholars and activists who argued that the food desert metaphor is equally freighted. Monica White, an assistant professor of environmental justice at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, points out that, even though the term has reduced the tendency to blame poor nutrition on individuals and their “lack of willpower,” it’s also shifted culpability to the neighborhood as a whole. “Somehow the community is at fault,” she says.

That fault-finding can come from within. Reese discovered that some Deanwood residents pointed to generational failings. I remembered that finding when Chandler talked about her own youth: “Soups, dumplings—women made things from scratch. And these young women barely know how to open the microwave.”

On the flip side, food deserts wrongly imply a geographical determinism—an inevitable surrender to processed and fast food, says Dara Cooper, an organizer for the National Black Food and Justice Alliance, who has influenced Reese’s scholarship. “So often, black communities are referenced”—by policymakers and even liberal advocates—“as passive, empty receptacles … completely ignoring what communities are doing themselves to drive solutions.”

Self-reliance has its limits. It’s rare that local fixes meet the needs of an entire community.

The solutions Reese witnessed in Deanwood are relatively modest. Elsewhere, communities have mounted more ambitious responses. In Oakland, California, Mandela Grocery, a worker-owned market, sources food from local farmers and offers deep discounts to families that use food stamps. Freedom Farmers’ Market, also in Oakland, specializes in traditional foods grown by African-Americans.

But self-reliance has its limits. It’s rare that local fixes meet the needs of an entire community, in part because they don’t eradicate those big upstream woes. That’s why it’s also important to document the way African-American communities have been abandoned. “Supermarket executives know that people are resilient, because people need food and they’re going to get food no matter what,” Reese says. “Just because I’m focusing on the ways that people are able to get food despite corporate failures does not let corporations off the hook.”

What happened in Deanwood was both city-specific and part of a larger exodus occurring in black neighborhoods around the country. After World War II, restrictive covenants, like the one barring home sales to “negroes” and to “Jews, Hebrews, Armenians, Persians, and Syrians,” began easing up in the District—aided, in part, by a 1948 Supreme Court ruling that declared the covenants unenforceable. That opened up more of the city to Jewish grocery owners. Then, in 1972, the District Grocery Stores co-op, formed in 1921 to strengthen the Jewish community’s buying power and fight anti-Semitism in the food industry, shut down. Merchants blamed competition from supermarkets, which had extended their hours to evenings and Sundays, along with a spike in crime.

“The small stores used to stay in business by staying open late at night,” one grocer told The Washington Post. “Now the only thing to wait for at night is someone with a gun.”

Meanwhile, supermarket executives were plotting their exodus from minority neighborhoods nationwide. Reese studied industry trade publications and discovered discussion of “embattled cities” as early as the 1960s. “Several chains have ‘had it,’” said a 1967 article in Modern Grocer, explaining that “chronic lawlessness” was forcing company executives to “reduce or eliminate entirely stores in … riot torn areas.”

Deanwood’s Safeway closed in 1980. For a few years, a black-owned grocery chain called Super Pride operated in the same building, drawing shoppers from around the region with traditional offerings like collards and hog maws (stomachs). It struggled, however, in the mid-1980s, when the nearby public housing complex was emptied for renovation. A few years later, the store was gone. (Another followed, Chandler says, but only briefly.)

By then, supermarket planners were coming to favor the ample square footage and easy parking of suburban strip malls. Stores were disappearing from urban neighborhoods, particularly those with large African-American populations. In 1984, Mother Jones reported that Safeway had closed 600 stores, many of them in inner cities, over the previous five years. Hartford, Connecticut, the same article noted, had lost 11 of its 13 chains since 1968.

Store locations, Reese concluded from her research, reflect larger patterns of racial segregation. (Even well-off African-American neighborhoods have fewer stores than their white counterparts, she noted.) “Want to know how/what inequality looks like in your city?” she wrote in a Twitter thread in January. “Trace the opening and closing of supermarkets.”

“Welcome to Deanwood,” Reese says after lunch, as I steer my rental car onto Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue. The road’s namesake emblematizes the neighborhood’s self-reliance: In 1909, Burroughs founded the National Training School for Women and Girls, which educated its mostly working-class black students in everything from power-machine operation to missionary work and didn’t solicit funds from white donors.

We park in front of the black-owned corner store that residents had regarded fondly. This was Reese’s first visit to Deanwood since the owner died three months earlier. She enters first, without me, and comes out crestfallen. The new management has gotten rid of the small vegetable section and erected a shield of Plexiglas in front of the cash register. The shelves offer little more than beer, canned soup, and snack foods, plus a few errant bags of flour.

“It looks like what we think of as a corner store now, in a way that it didn’t look before,” she says. “That catches me completely off-guard.” She lets out a long, audible sigh.

We continue on to the public housing community. It’s a vast complex of brick buildings laid out in hilly tiers. Outside, young men play basketball and an ice cream truck (“which may or may not be a real ice cream truck,” Reese says) makes slow rounds. The complex is slated for demolition, and many of its buildings are boarded up. Despite policy efforts intended to “eliminate food deserts,” no new stores have come to this neighborhood. In truth, interventions would need to target the damage of structural inequality, poverty, and racism to make meaningful change. In the meantime, the people of Deanwood have to find their own fixes.

We climb some concrete steps to view the garden Reese had described over lunch. All that remain are a single fallow bed and a waterlogged patch of dandelions and grass.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

Reese laughs sadly. She uses the moment to reflect on what she calls the “limits of self-reliance.” Even the Freedom Farm Cooperative, she observes, which civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer founded in Mississippi in 1969 as a model of community-based economic development, shut down after four years as external funding dried up.

Reese isn’t totally surprised by this outcome. But it still hurts to see it on her return visit. “I am just going to get my heart broken in a bunch of different ways today,” she says, surveying the ruins.

This article was republished at Civil Eats.