How Some Tried—and Failed—to Kill “Race” in Latin America

When the structure of DNA was first revealed in 1953, it started a revolution. In the space of a few decades, the time and money it takes to sequence an entire human genome was slashed from 13 years and US$1 billion to two days and US$1,301. The world quickly became entranced by the aura of DNA, with the gene becoming a cultural icon with seemingly magical powers.

There is a lot to be gained from genetics, to be sure. Medical genetics has mushroomed as scientists promise to track down genetic traits that might help treat modern disease epidemics such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. The powers of forensic identification have expanded exponentially, giving law enforcement vastly improved abilities to track criminals and bring them to justice. Genetics is an increasingly crucial component in humanitarian endeavors to reunite families with the remains of loved ones killed in disasters or war crimes. Genetics has also taken us deep into human history, uncovering the earliest migrations and intermixings of populations of Homo sapiens and human relatives such as Neanderthals.

But not everything this genetic revolution has brought to society has been good.

I became interested in DNA technologies when I saw how they were being used in Latin America, where I have long carried out anthropological research into racism and racial inequality. Genome analysis in general has confirmed the idea that there is no genetic basis for the concept of “race”; yes, some groups of people are indeed different from one another genetically, but these groupings don’t align with the groups socially defined as “races.” In this way, genetic science has helped to dismantle the mistaken idea of biologically defined “races.” But, sadly, this is not the only way in which genetic data have been used.

Though DNA data has been used to knock down the walls of biological race, genetic ancestry testing has also been used to support ideas of biological difference that reinforce the walls of racism. The type of genetic testing I am talking about is the sort that aims to identify what percentage of a person’s genome comes from certain ancestries, such as “African” or “Western European.” Across Latin America, I have seen genetics used counterproductively to support racial stereotypes, reinforce the idea of racial purity, and refute anti-discrimination policies. Genetics is being wielded as a double-edged sword.

My research, encompassing over three decades of fieldwork in Colombia and surveys of the academic literature, showed that Latin American pundits and political leaders frequently depicted their nations as relatively free from the scourge of the racism that, according to them, was typical of the United States. They argued that democracy was a natural outcome of the region’s history of race mixture, in which colonizing Europeans had children, sometimes through violent encounters, with enslaved Africans and Indigenous people to form populations in which “mestizos” (people of mixed biological and cultural heritage) became a large and socially recognized category.

As early as 1861, Colombian writer and politician José María Samper rejoiced in the idea that “this marvelous work of the mixture of races … should produce a wholly democratic society, a race of republicans, representatives simultaneously of Europe, Africa, and Colombia.” (All translations in this piece are my own.) In the 1920s, the Mexican politician and intellectual José Vasconcelos famously trumpeted the virtues of the “cosmic race,” of which Latin Americans were the harbingers. Their mestizo character endowed them with the “transcendental mission” of uniting all people “ethnically and spiritually,” and bringing about the “social and civic equality of whites, blacks, and indios.”

In mid-20th-century Brazil, the image of the country as a “racial democracy” became official ideology. While the view from the street might have been different—with Black, Indigenous, and mestizo people complaining of racial discrimination and white elitism—the media, officials, and many intellectuals presented racism and race mixture as incompatible, like oil and water.

Genetics is being wielded as a double-edged sword.

Jump forward to the year 2000, when Brazilian geneticist Sérgio D.J. Pena and colleagues published a “molecular portrait of Brazil” in a popular science magazine, summarizing the results of their DNA ancestry testing of a sample of Brazilians. The tests showed that even those who self-identified as white had appreciable amounts of African and Amerindian ancestry in their mitochondrial DNA. (MtDNA is a tiny part of the genome inherited by men and women via the mother and in unchanged form, allowing geneticists to look far back along an unbroken maternal line and locate specific mutations known to have originated in certain regions, such as Africa, Asia, or the Americas.) At the end of the widely reported article, admitting they might be accused of naiveté, the geneticists speculated that if white Brazilians were to become aware of their genetic ancestry, “they would value more highly the exuberant genetic diversity of our people and, perhaps, would construct in the 21st century a more just and harmonious society.” This is the same idea of mixture equaling peace as expressed in previous centuries, now bolstered by personalized DNA data.

My research on genomic science in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, carried out with a team of colleagues, revealed that Pena and his co-authors were outspoken about how DNA data could be used to address social issues, especially racism. They insisted that Brazilian mixed populations provided the perfect demonstration of the idea—already taken as fact by most geneticists—that coherent biological “races” cannot be defined within the human species. In a 2006 article, Pena took a step further and argued that “this scientific fact of the nonexistence of ‘races’ must be assimilated by society” and that awareness of this fact “meets the utopian wish of a nonracialist, ‘color-blind’ society.”

In Colombia and Mexico, the geneticists my team and I researched were less outspoken about racial issues and confined themselves mostly to the medical and forensic uses of DNA that provide the bread and butter of genomic science worldwide. Even so, they consistently reiterated the idea that people in their countries—including those who saw themselves as Black, Indigenous, and white—had nearly all inherited some combination of DNA from people of African, Amerindian, and European origins. “We are all mixed,” an apparently self-evident truth often repeated in support of this idea of societies free of racism, now had the backing of a science that could delve into each person’s genome and tell them exactly how mixed they were.

If genetics were solely being used to demonstrate biological mixedness, break down the walls of “race,” and support social harmony, that would be wonderful. But that’s not all that’s going on.

Despite a long history of officials and others touting Latin America’s mixed roots as a source of supposed racial harmony, there is still significant racial discord in its nations. Indigenous and Black minorities have long begged to differ with the pundits’ view of Latin America as an egalitarian utopia.

In early 19th-century Colombia, Black military officers complained of discrimination, as did Black-run newspapers in São Paulo, Brazil, in the 1920s and ’30s. From the early 1950s, when UNESCO launched a research program in Brazil designed to test the truth of racial harmony claims, the discrimination complaints were increasingly supported by research documenting the extent of racial inequality in Latin America and the role of racism in sustaining it. For example, in Brazil, compared to whites, Blacks earn half as much, their illiteracy rates are more than double, and their maternal mortality rates are over 40 percent higher. One study calculated that 24 percent of the wage gap between Black and white men was due to racial discrimination.

Genetic tests play a role in reaffirming ideas about racial difference that help reproduce racial inequality. Although often used to emphasize biological similarity among people, they are also used the exact opposite way. The presentation of genetic data has the perverse effect of accentuating the small differences that exist between people identified as Black, Indigenous, mestizo, and white in terms of the average percentages of European, African, and Amerindian ancestry these groups have. This backgrounds the fact that all humans are currently estimated to be about 99.9 percent genetically identical.

Emphasizing biological difference has in the past been a cornerstone for racist beliefs, and, if current genetic science also highlights genetic differences, it runs the risk of underwriting racism once more. Take the idea, fundamental to DNA ancestry testing, that a person has X percent African, European, or Amerindian genetic ancestry. These estimates are made using samples from present-day reference populations, which are taken pragmatically as the best available examples of these ancestries. However, it is all too easy for the casual observer to conclude that, relative to a “mixed” person, these reference populations are 100 percent—in other words “pure”—African, European, or Amerindian. This resurrects the ghost of the biologically defined “races” that genetics has worked so hard to lay to rest.

Then there is the way that DNA data has been used in the wider public domain—including by people well-versed in the niceties of genomics. Pena himself weighed in on the controversy that was raging in Brazil in the early 2000s around race-based affirmative action. The debate centered on admissions quotas for Black applicants to public universities, which critics said were unfair and created more racial friction. Providing grist for the mill of the critics, Pena argued that because races did not exist in human biology, they should not be used as a basis for affirmative action policies. There was no biological basis for the “Black” category, he wrote in his 2006 article, that had been enshrined in Brazilian law. Supporters of the quotas refuted this argument, pointing out that no one was saying that “Black” was a genetic category.

The point of the quotas was to address the fact that people perceived as Black were being discriminated against by the people who controlled valued resources and opportunities; the discriminators paid no attention to genetics. Black activist Frei David dos Santos remarked that “I’ve never seen any police bus searches, for example, which, before discriminating, asked a person what percentage of Afro genes they have.”

There are other examples, too, of people in Brazil using genetics in an attempt to undermine race-based affirmative action policies. In 2007, BBC Brazil carried out DNA ancestry tests on nine celebrities to investigate their “Afro-Brazilian roots.” The samba singer Neguinho da Beija-Flor, widely seen as an Afro-Brazilian cultural icon, was found to have 67 percent European ancestry. Although he brushed off the result as having no impact on his own and other people’s perception of him as unequivocally Black, this DNA result was widely touted as proving that it was impossible to define a category of Black Brazilians who could be the legitimate beneficiary of public policies.

A legitimate denial of biological race was used to undermine a social struggle that aimed to correct the well-documented disadvantage caused by past and ongoing racism in Brazil.

DNA has also been used to reinforce as well as challenge social identities. In Colombia, some geneticists homed in on their own city of Medellín, the capital of Antioquia, a province known as the home of the paisas. The paisas are a regional group of people who are often stereotyped in Colombia, and who often stereotype themselves, in terms of their business acumen, work ethic, migratory and entrepreneurial spirit, fierce sense of regional pride, … and whiteness.

In scientific publications, these researchers showed that people from Medellín and from small towns in the region’s historical heartlands had very high levels of Amerindian ancestry in their mtDNA (inherited down the maternal line) and high levels of European ancestry in their autosomal DNA (inherited from both parents). This is not uncommon among most Latin Americans, who carry in their mtDNA the genetic marks of the (at times horrifically violent) sexual encounters between European men and Amerindian and African women.

The research also labeled the paisas as an “isolate,” defined as a population that had seen little genetic exchange over the period from the initial influx of conquistadors until the mid-20th century, when the movement of people worldwide began to rapidly accelerate. Again, this is not uncommon: Most national or regional populations in Latin America would also qualify as genetic isolates if defined in this way (with the exception of those in Argentina and Brazil, because together they received some 11 million European immigrants between 1870 and 1930).

It is vital to remember that the way humans categorize one another obeys social and cultural drivers.

Yet, despite these somewhat predictable findings, the research was widely used to support the idea that paisas are special, reinforcing their perceived whiteness. A major radio network headlined a story on the research: “Confirmed: Antioquia Is a So-called Genetic Isolate; The Antioqueños Are 80 Percent European.”

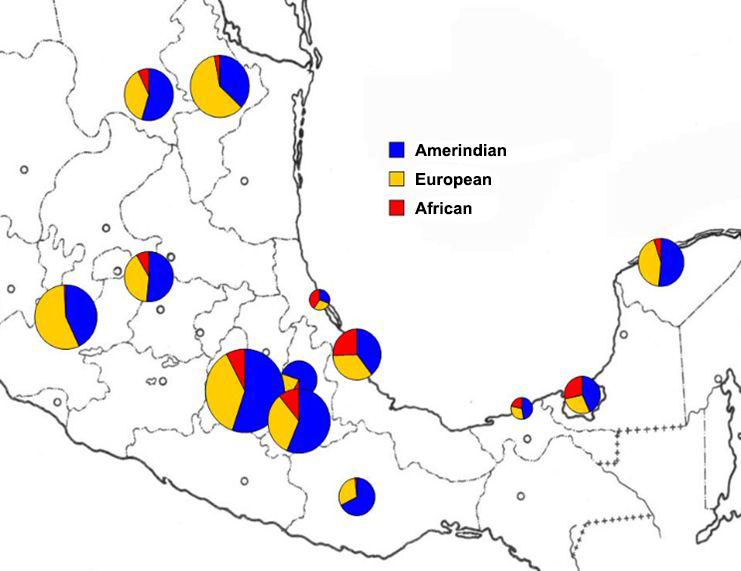

The use of genetic tests can have other perverse outcomes. In Mexico, the government chose to fund genomic research much more than in Brazil or Colombia. The flagship project of Mexico’s National Institute for Genomic Medicine was to create a map of Mexico’s genetic diversity. The results, published in 2009, showed, not unexpectedly, that the vast majority of Mexicans are genetically mixed, with the precise profile of the mix varying by region. This variation was familiar to Mexicans themselves, who already knew that the south of the country had more Indigenous heritage than the north.

Subsequent projects in Mexico have focused on possible genetic causes for the country’s skyrocketing rates of obesity and diabetes. The finger is currently pointing at genetic variants identified as having been passed on from Indigenous ancestors.

The economic value of this focus on genetic causes has been questioned, given that diet and lifestyle are known to be very important contributors to these health problems. More problematically, these projects attempt to make a biological distinction between mestizos and Indigenous people (even as they also show that many Indigenous people themselves have some genetic ancestry from mixture with people of European origins). The social distinction between mestizos and Indigenous people, traditionally marked by cultural features such as language and clothing, is given a genetic load—a negative one for Indigenous people, who are identified as having passed down risk-bearing genes. As in Brazil and Colombia, DNA has become entangled in social distinctions and is sometimes used to reinforce racial hierarchies.

Genetic science has already proven its contribution to human well-being, and it harbors huge potential to do even more. At the same time, there are well-founded fears about the possible misuse of DNA to aid eugenics-style selection (as in “designer babies”) and to criminalize certain sectors of the population through the creation of bias in DNA databases. My research in Latin America shows that dangers also abound in the way DNA data are used in understandings of racial difference. There is an ever-present danger that genetics is brought in to adjudicate on racial identities such as Indigenous, Black, and mestizo, which are cultural artifacts defined by colonial and postcolonial hierarchies of race and class.

There is no denying that there are significant genetic differences among humans that affect individual health prospects. There is debate among geneticists about exactly how these differences are organized into populational patterns and even more dispute about whether such patterns align with what biologists and others previously called “races.”

It is vital to remember that the way humans categorize one another obeys social and cultural drivers. People are all too tempted to think of the categories they create as rooted in nature, and this can be used to justify discrimination and inequality. Geneticists—and the public—need to be more conscious of the easy and potentially harmful slippages that occur from culture to biology and back again, both in genetic research practices and in the way genetic data are used in wider society.