Deaf and Incarcerated in the U.S.

I grew up wearing two hearing aids and currently have two cochlear implants. From a young age, soon after I was diagnosed as deaf, audiologists and speech and language pathologists instructed my parents to make sure that I always wore my hearing aids. [1] [1] Editors’ note: Some people capitalize “Deaf” when describing themselves and/or when referring to the culture and community of Deaf people. As per The Diversity Style Guide’s recommendations, we follow individual preferences in using the lowercase or uppercase “d” in “deaf” as an adjective. That way, I could “live up to my potential,” they said. According to the professionals, listening and speaking was essential to participating in “normal” life and becoming successful.

And indeed, hearing technology enabled me to fit in and perform well in mainstream educational settings—although it did not reduce the structural barriers that existed and continue to exist for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals.

Today I’m an anthropologist who focuses on deafness and disability. I currently study the emergence and circulation of different auditory therapy techniques and hearing technologies, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants. I am interested in what these techniques and technologies enable in terms of social life.

I’ve learned that my family’s trajectory was not unique; audiologists and speech and language therapists, drawing on neuroscience research, consider hearing loss to be a “neurological emergency” that must be immediately addressed through technological intervention. Parents of deaf children, such as John and Ginny Croft, stressed in essays and speeches in the 1970s that their young daughter was never without hearing aids during all of her waking hours. If a hearing aid broke, it was quickly repaired.

These parents, like my parents, thought that auditory technology was incredibly important to creating and maintaining social and educational development.

This attitude contrasts starkly with how deafness and hearing loss are treated in carceral systems in the United States.

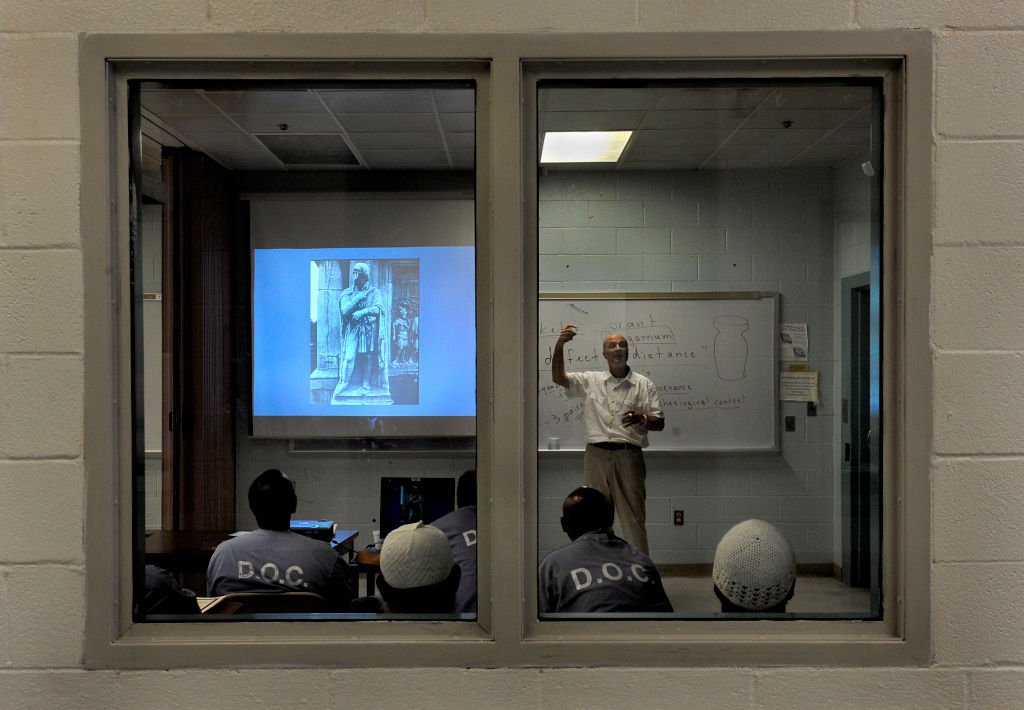

In an ongoing research project, I have been communicating with incarcerated people and looking at different state Department of Corrections (DOC) policies and practices of providing hearing aids to incarcerated people. I’ve found that deaf incarcerated people’s needs are routinely dismissed or minimized by prison authorities.

The well-documented lack of adequate accommodations and access provisions for a range of disabilities is widespread across the criminal justice system, from policing that targets those with mental health issues to prison health care systems that deny wheelchairs, prosthetics, and specialized diets to inmates.

Over the course of my research, deaf incarcerated people have told me about trying in vain to have broken hearing aids repaired, sleeping with uncomfortable hearing aids to avoid missing a guard’s instructions, and straining to hear in incredibly noisy prison environments. One person told me he wished that his hearing aid would work immediately after he turned it on; instead, he had to wait for a series of “merry-go-round” beeping sounds that signaled the device was about to turn on. It was especially harrowing when an officer came to his door while he was asleep, and he had to tell them to wait for him to get his hearing aid in and working. “Anything can happen!” he wrote to me.

Having functioning hearing aids in prison can be a high stakes situation. Not hearing a guard’s order can lead to being written up. Missing an announcement for roll call or meals can mean being marked absent or not being able to eat. Not hearing sounds and speech can also lead to safety issues, such as vulnerability to prison violence, as well as an inability to take advantage of prison programming.

How does the carceral system in the U.S. systematically deny access to deaf incarcerated people?

Unlike deaf children, deaf incarcerated people are generally not seen as having “potential” that deserves nurturing through auditory technology. They experience communication limitations and language deprivation related, for example, to the lack of American Sign Language and other sign languages. Prisons also often do not provide accessible telecommunication devices.

I focus here on hearing aid provision, not because hearing aids are more important than other forms of access but because of the clearly discriminatory policies that contrast sharply with how childhood deafness is treated by experts.

Many states have policies to provide incarcerated people with only one hearing aid, even if a person experiences hearing loss in both ears. (In these cases, hearing aids are typically provided only for the better ear, while the worse ear receives nothing.) Exceptions can be made if a person has vision loss or other sensory disabilities, but in most cases, the policies, in a nutshell, state: If a person needs two hearing aids, they are entitled to one. If they need one, they get none.

I should not have been surprised by these kinds of policies.

In Illinois, where I live, the Department of Corrections came under fire in 2019 for their unofficial policy to provide incarcerated people with one cataract surgery even if both eyes had cataracts. Prison health officials, employees of a privatized corporation named Wexford Health Sources, had apparently argued that people only need “one good eye” in prison. This practice has ostensibly ceased after public outrage. However, the fact that incarcerated people only need “one good ear” follows the same kind of logic.

Over the last 10 years, there have been a number of class action lawsuits and subsequent settlements on behalf of deaf and hard-of-hearing incarcerated people that have included a focus on hearing aid provision. In Michigan, Illinois, Kentucky, Virginia, and Florida, to name a few, these lawsuits have pointed to the outsized role that DOCs play in providing and denying health care and disability access in carceral contexts.

Although an Illinois lawsuit now permits a licensed audiologist to make the decision about hearing aid needs, many of the other lawsuit settlements have left intact the “one good ear” policy. In Washington state, for example, the policy requires a person have moderate hearing loss at three different frequencies in order to be eligible for even one hearing aid.

Based on such policies, incarcerated people might have moderate hearing loss in both ears or moderate hearing loss in one ear and severe hearing loss in the other ear—and even then, they will only be entitled to one hearing aid.

What’s so difficult about having only one hearing aid?

To start, it hinders localization, making it difficult to know where sounds and speech are coming from.

Having only one hearing aid also necessitates increased cognitive work; people need to work harder to hear and then make sense of what they are hearing—an especially difficult task in prisons. Deaf incarcerated people must find ways to navigate these notoriously noisy environments, where fellow incarcerated people routinely yell across cells and bang on bars, and orders and announcements come over loudspeakers and reverberate across concrete floors and walls.

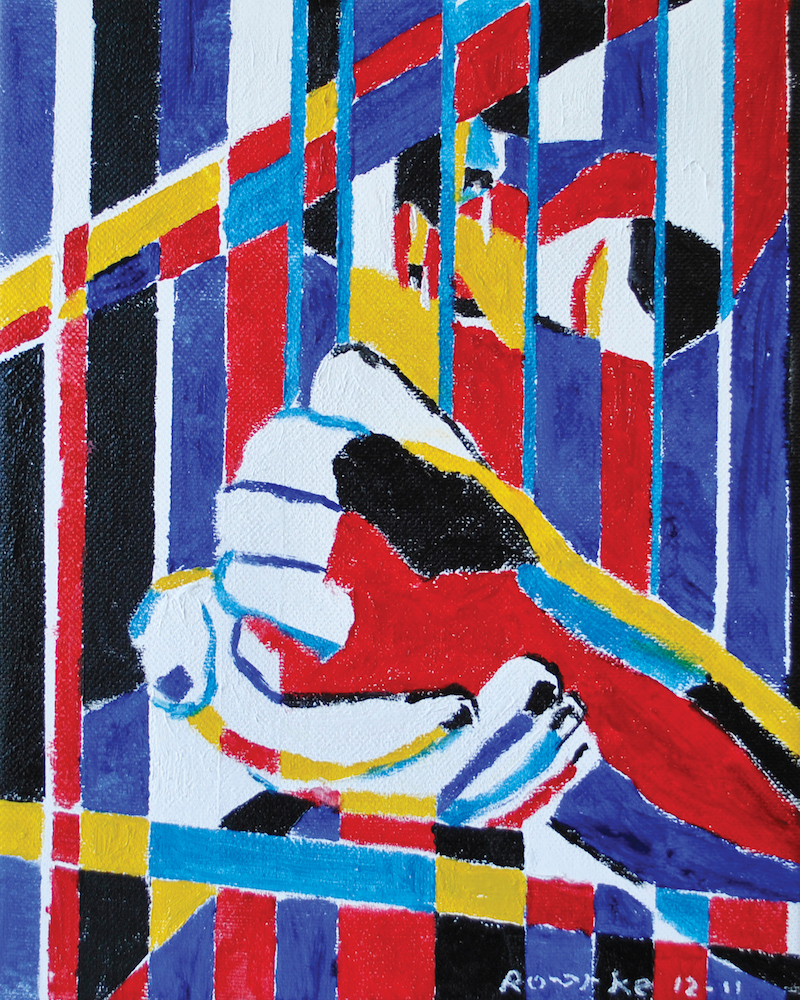

These limited policies say a lot about how the carceral system conceptualizes what kind of sensory engagement is “good enough” for incarcerated people. Criminologists, sociologists, and disability studies scholars have stressed that the harsh physical and emotional conditions of the carceral system itself are disabling.

What, then, is the carceral system doing to maximize, or even maintain, the abilities that people currently have? Intervention into hearing loss is only permitted to the extent that it is “medically necessary.” But if medical necessity is about maintaining and preserving life, what kind of life is being preserved?

My research suggests that the language of “medical necessity,” in practice, is less about providing care and more about maintaining surveillance and keeping incarcerated people biologically alive.

Prison documents from Washington state, for instance, assert that the single hearing aid is considered “medically necessary” for incarcerated people to be able to “hear overhead announcements” and “become aware of hazards earlier” in order to assess unsafe or dangerous situations. The documents also acknowledge that aided hearing can encourage more participation in prison programs and “contribute to quality of life,” but these concerns appear secondary.

These statements from prison authorities reveal the limited understandings of “medical necessity” and sensory thresholds that are allowed in carceral settings. They acknowledge that aided hearing is key to improving a “social, psychological, and physical sense of well-being,” yet they refuse to maximize incarcerated people’s sensory capabilities and potential by providing access to necessary technologies.

With increasing public attention on the need to reimagine the criminal justice system—including calls to defund the police and abolish prisons—changes may be on the horizon. However, given entrenched structural inequalities and the pervasive presence of ableism in the U.S., specifically in relation to education, health care, and economic investments, the way forward is unclear. In addition to rethinking the criminal justice system, these struggles over access to hearing aids within prisons must be seen as part of broader calls for disability justice.

The refusal to provide hearing aids or cataract surgery lays bare the kinds of sensory, and social, deprivation that take place in prisons. Incarcerated people are being kept alive, but what kinds of sensory or embodied life do they have access to?