Confronting Xenophobia Through Food—and Comics

Before I left India for the U.K., my mother stuffed bubble-wrapped jars of spices into my bags—a secret concoction of dried and toasted cumin, coriander, dried coconut, curry leaves, and red chiles. She also insisted on packing assorted homemade snacks to be delivered to a cousin in London, despite my protests that I would have no space for my clothes.

When I landed, I was handed more of these culinary essentials by my family and friends who had previously settled in London: foods that would remind me of home.

My family comes from the states of Maharashtra and Goa on the western coast of India, which, like all subregions of India, is known for unique flavors and food preparations. Our foods are still difficult to find in the United Kingdom, despite the ubiquity of “curry houses” and supermarkets selling “Indian” items.

Indian cuisine in the U.K. has transformed over the decades in relation to changing geopolitical relationships. During the Victorian period, roughly 1820–1914, British expatriates returning home after spending time in colonial India popularized “curries” among some British consumers. But until the middle of the 20th century, most Britons stayed away from curries due to racist stereotypes of South Asians being “dirty” and the food being “smelly.”

This started to change after the passing of the 1948 British Nationality Act, a year after the end of British colonial rule on the Indian subcontinent. This act, which granted citizenship to people who lived in the British Empire and Commonwealth, also overlapped with the post–World War II labor shortage. It led to a huge influx of students and laborers from across South Asia to the U.K. Local eateries catering to working-class South Asian migrants popped up in neighborhoods with large migrant populations, such as the now-famous Brick Lane in London, creating new markets for imported foods from India. Over time, these foods become more widely eaten across the U.K., expanding the Indian food market further and eventually bringing curry sauces and spice mixes to the shelves of popular supermarkets such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s.

Today Indian food—or at least a certain Anglicized version of it—has become part of the national diet in the U.K. Over the last few years alone, sales of spice blends like garam masala have grown by 24 percent. Yet, with mainstreaming and homogenization, much of the food has become unrecognizable to Indian migrants—a view shared by many of my interviewees. Popular dishes like chicken tikka masala, vindaloo, and balti have gained more popularity in Britain than in India and have been adapted to the palates of primarily White British consumers.

As an anthropologist, artist, and migrant, I became fascinated by the popularity and adoption of “Indian” cuisine when I first arrived in the U.K. When my non-Indian friends talk about their love for Indian food (albeit a British version of it), it often leads to opportunities to discuss other aspects of Indian culture that were unknown to them.

This seeming embrace of foreign food culture contrasts with the stark nationalism and xenophobia that many migrants have witnessed in the time of Brexit and new anti-immigrant legislation introduced by the government. Most recently, the controversial plan to deport asylum-seekers to Rwanda has revealed the ugliness of British xenophobia and racism.

Read more from the archives: “When ‘Voluntary’ Return Is Not a Real Option for Asylum-Seekers.”

The comics below, based on my research with migrant communities in London, explore how food and culture interact with xenophobia and migration. The popularization of Indian cuisine in the multicultural U.K. has only been possible due to migrants—especially women, who do most of the food shopping and preparation within families. To explore these processes of cultural maintenance, I went on an anthropological tour of my own community’s migrant food spaces—ethnic stores, markets, and kitchens.

The illustrations consider how migrants maintain their cultural identities by obtaining heritage ingredients, cooking familiar dishes, and passing on and preserving other food habits in the face of decades of cultural homogenization and growing xenophobia.

HERITAGE AT HOME

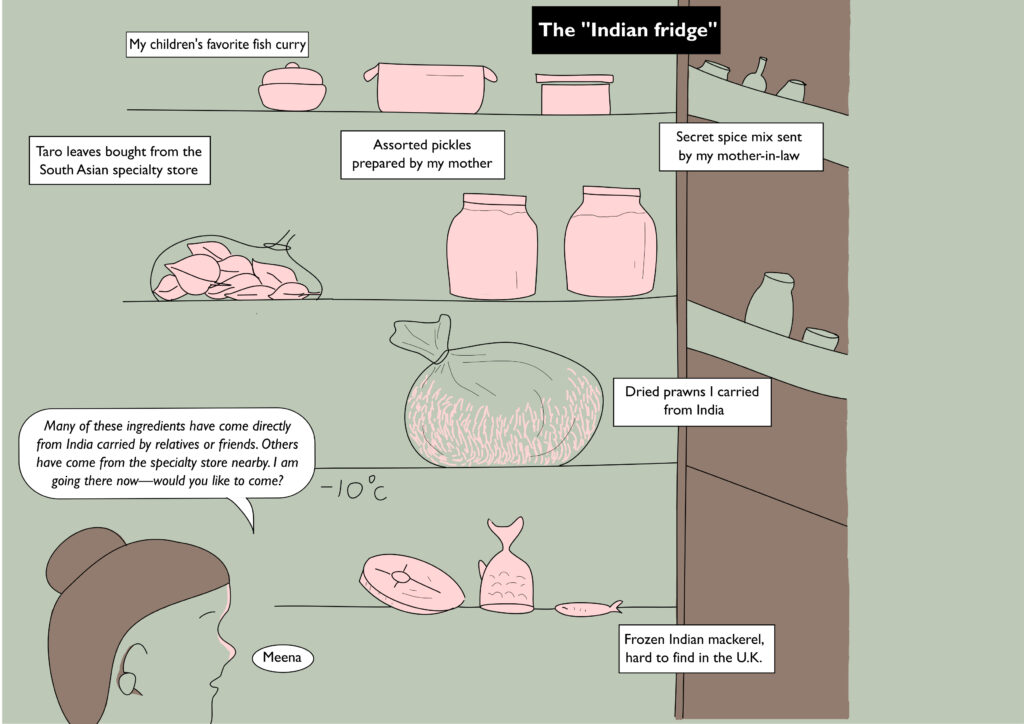

Meena, one of my interviewees, showed me her “Indian fridge.” [1] [1] All names of interviewees are pseudonyms. Most people do not have a separate fridge for special heritage ingredients. However, most find ways of accessing and using these products to preserve traditions. Meena makes sure she cooks her children’s favorite fish curry, a dish that ties them to their Maharashtrian heritage. She also stores dried fish that she bought in India, which reminds her of flavors she grew up with.

FISH MONGERS AND COMMUNITY

I accompanied Meena to an ethnic food store in London where she bought some of the ingredients in her fridge. The shop, which sold a variety of imported fish, vegetables, and spices, catered to a large multicultural South Asian community in the suburban neighborhood of Hounslow. The community’s demand for ethnic goods led to the establishment of these kinds of shops throughout suburban London. I found these stores also played a role in making South Asian culture and cuisine more visible to the general public.

EARLY MORNING MARKET RUN

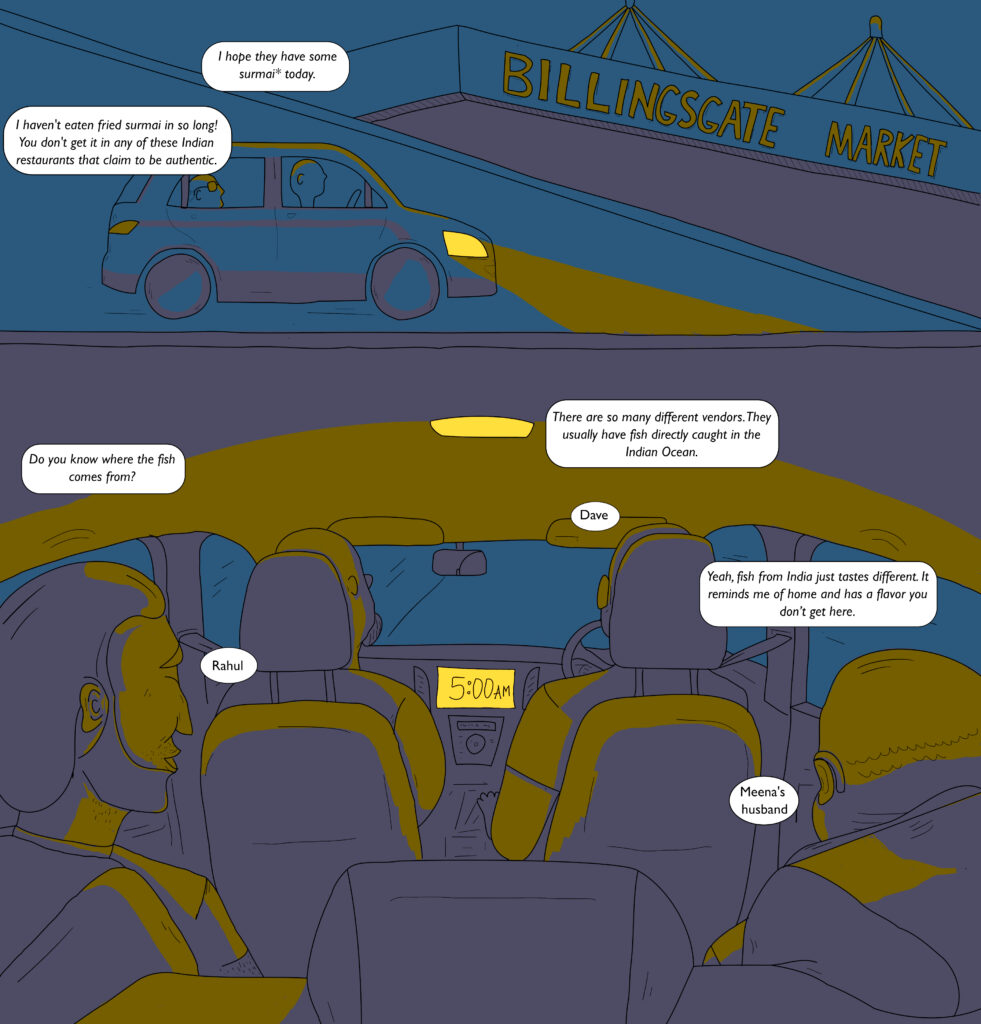

Meena also told me some of the seafood in her fridge had been bought at Billingsgate Market at Canary Wharf, London, where seafood imports arrive from all over the world. Her husband and a few others from the community, such as their friends Rahul and Dave, visit every month to purchase fresh seafood caught in the Indian Ocean. The journey takes more than an hour by car each way and requires they leave very early in the morning. But it’s worth it to them.

* Surmai is the Marathi word for kingfish.

Everyone I talked to for my study went to great lengths to make sure they could access Indian ingredients for cooking traditional dishes.

British favorites like kebabs, curries, and noodles only exist because of the migrants who have actively worked over decades to maintain their identities through food. For Meena, like me, food is comfort. It’s also a conversation starter and a tool of resistance against prejudice. Every time a migrant in the U.K. buys a heritage ingredient, it’s a step toward defying the institutional erasure of multiculturalism.