When Coronavirus Emptied the Streets, Music Filled Them

Since a quarantine was imposed in parts of Italy on March 8 to stop the spread of COVID-19, I’ve been struck by the silence. In a place where people love to engage, touch, talk, and constantly debate, the lack of sound—especially of people’s voices—is eerie.

On the island of Sardinia, where I have lived since June, the silence is palpable. It seems to weigh on the landscape. [1] [1] On the advice of the U.S. State Department, the author had to temporarily leave Italy due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

On March 11, the policy of “shelter in place” went from being recommended to being mandatory. All bars, restaurants, cafés, and other “nonessential” businesses were closed until at least April 3.

From my open door in the seaside city of Cagliari, I see only occasional passersby, walking briskly and purposefully down the city’s main shopping street, dutifully clutching their autodichiarazione—papers that justify their reasons for leaving home.

In train cars, grocery stores, and pharmacies, the smell of bleach and hand sanitizer assaults the senses. Strikingly absent is the aroma of strong espresso, usually a ubiquitous part of the city’s olfactory landscape.

City squares are hosed down each night with large water tanks. Police officers patrol the roads. In a city known for its rich and fecund smells, its sensuous approach to life, and its vivid festivals, the streets feel sterile and empty.

But into this void of daily scents and sounds, a multitude of melodies has been born: balcony concerts, recordings, and in-home videos under the hashtags #flashmobsonoro, #iorestoacasa (“I’m staying home”), #lamusicanonsiferma (“the music doesn’t stop”), and #tuttoandràbene (“everything will be OK”).

These performances—original songs, covers, spontaneous performances, and humorous commentaries—are a sonic response to this government-imposed silence. Each of us is reaching out across the ether, from the solitude of our home to someone else in the solitude of their own home.

I came to Sardinia to study the Sardinian language, conduct anthropological fieldwork, and write and record an album with Sardinian songwriters. I was drawn to the intensity of social life on this island, its incredible culture of hospitality, and the profound appreciation people here have for music and sound.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended much of that research. But it’s also revealed new and important ways in which music echoes and amplifies the tensions that vibrate through Sardinian daily life. The songs emerging from the quarantine are a profound form of social commentary on Sardinian perspectives of power, relationships to the Italian mainland, and the ways the virus has rocked longstanding ideas of privilege and status between Italy’s north and south.

On March 12, a song arrived on one of the lively WhatsApp groups I am part of. It spoke eloquently of the connectedness of cultures. In the video, Antonio Pani plays an Irish bouzouki in a Sardinian style, wears an Oregon sweatshirt, and sings a Spanish-influenced tune reminiscent of the storytelling corrido ballads of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, where I lived and studied previously.

The style—cantu campidanesu—is a poetic form of song well-known on the island. The genre, called gòcius or gosos, is Iberian in origin, and harkens to a time when Sardinia was colonized by Spain from about 1325 to 1708. It is primarily religious, but in its secular form, a gòcius often satirizes a person or an issue of the day. They can also be songs of protection for people, the harvest, and livestock.

In the song—called “Su Baballoti,” or “the cockroach”—Pani uses the metaphor of a cockroach to convey how the novel coronavirus (sa corona) has crawled into every nook and cranny of everyday life. He references face masks and laments the suspension of kisses during greetings and goodbyes, and the absence of gestures like the brief brush of a hand on an arm to affirm connection.

It reminds me of the day before the lockdown, when I was sitting alone in an outdoor café. A man asked the people at a neighboring table for a light. As he held out his cigarette, his girlfriend reminded him, in Italian: “Respect the social distance of 1 meter.”

Pani plays with the word “corona,” which also means “crown” and symbolizes power. He addresses the novel coronavirus, singing in the southern version of the Sardinian language, Campidanese: “Even if you walk around with a crown / you will never be our king.”

He describes the powerful ways the pandemic has impacted Sardinia and the northern Italian region of Lombardy. “Italy is in torment,” he sings. “Sardinia has also been affected but not like Lombardia, which remains in our thoughts.”

Then he stares straight at the camera and earnestly sings: “Baballoti, get away from here. You will not win.”

Another song circulating is an example of Sardinia’s traditional cantu a tenòre style, which UNESCO designated an intangible cultural heritage. It imitates a type of rhythmic song that accompanies village dances and features four male voices singing a cappella in Sardinian-inflected Italian and low, guttural voices. The lead singer-songwriter is Sardinian comic and cabaret singer Giuseppe Masia, and his tone is both cheeky and deadly serious.

The song documents the 13,300 Italian northerners who fled to their second homes in Sardinia over the last two weeks, right before the borders of Veneto and Lombardy were cordoned off and declared “red zones.” Thirteen thousand is a number equivalent to all the visitors who come to Sardinia during the Italian vacation months of July and August.

The recent influx has, understandably, been the source of much consternation among Sardinians, who see these “northerners” as the main vectors for the virus.

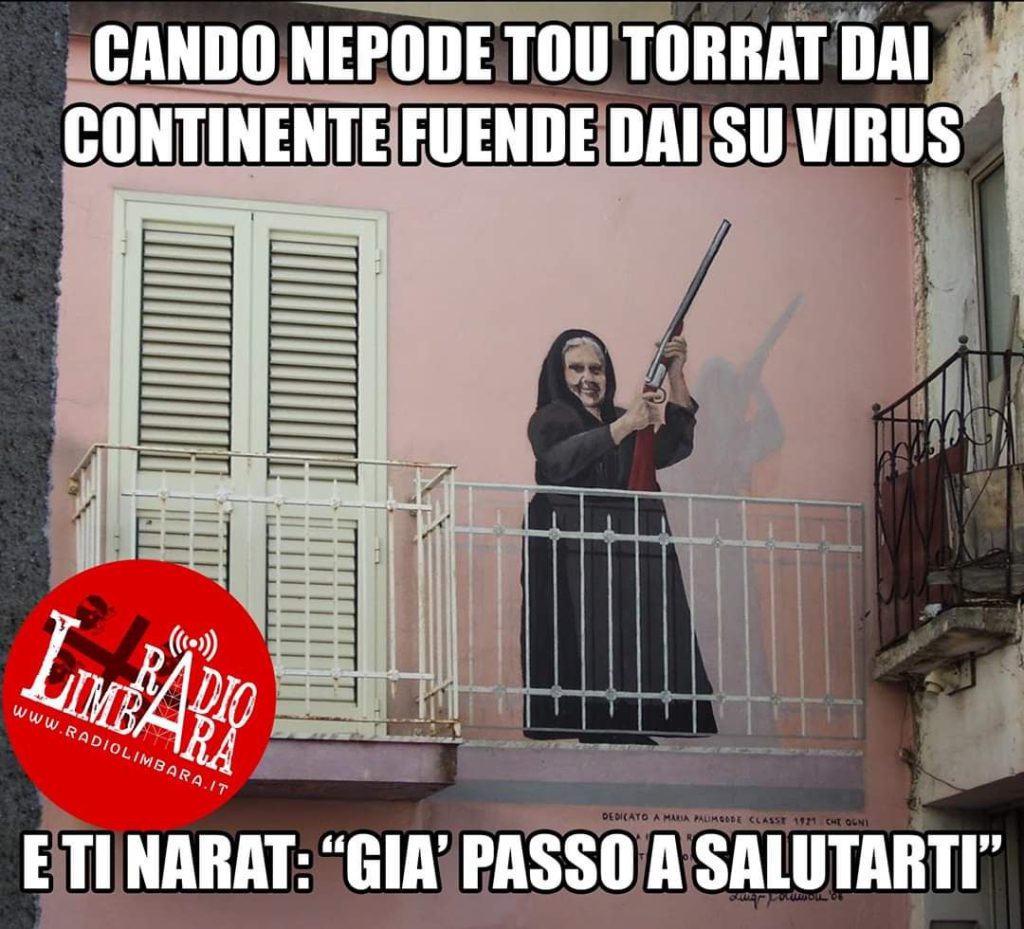

Masia sings in a strident, nasal voice, with the three accompanying voices pulsating underneath his: “Coronavirus: When you can’t find a face mask anywhere (they were all purchased by Aunt Gavina) / and the people give you dirty looks when you breathe in public.” The song ends with Masia threatening, in a melodramatic style, to shoot any “Milanesi” (people from Milan and elsewhere in the north) he meets on the street.

The situation represents a bizarre reversal of a centuries-old dynamic in which poor southerners, including Sardinians, move to northern Italy for work. (Unemployment in Sardinia right now is over 30 percent.) Northerners have often treated southerners as “hicks,” or terroni (“people of the earth”). They have viewed them as symbolic vectors for poverty and lack of education, and as literal vectors for disease.

And in a perhaps unprecedented moment of reversal, this disease has hit communities of privilege first—in Italy but also elsewhere—and socially marginalized communities last.

On one hand, wealthy northerners recently arrived in Sardinia on ferries with their cars packed full of food, ready to hole up in their beach houses, and either unaware of their privilege or unconcerned that they might bring the disease to an island long perceived by mainlanders as remote and desolate. The Sardi (Sardinians) feel taken advantage of and exploited.

On the other hand, in their quickness to judge their northern neighbors, some Sardi are repeating the exact behavior visited upon them while living on the “continente.”

So, COVID-19 has created a moment of truth, when the tables are finally turned.

But many of these northerners are also Sardinians who live, study, and work in Milan and other industrial centers, send valuable stipends back home, and have claims to family, villages, and homes in Sardinia. So, the people Masia threatens to harm might be members of his extended family.

In a time when the enemy can potentially be anyone, the novel coronavirus is both dividing and dissolving our distinctions between “us” and “them.”

Italy is a place where there is no word for privacy. In Italian, people have to borrow the English word “privacy.” The constant kisses, touches, exclamations, and opinions can at times be overwhelming for newcomers.

But I have never longed for the sense of social overwhelm and intense human contact that I associate with Sardinia like I have during this quarantine.

On March 13, I took part in a #flashmobsonoro. Each participant was supposed to play songs from our balcony for 15 minutes, then post the video to Facebook.

I live in an underground apartment with no windows, so I performed from my doorway, with my dog at my feet. I played four original songs, three country songs in a mix of Sardinian and English, and one folk song in Norwegian. As my Sardinian language teacher taught me, in the chorus I sang:

“Nois tenimos sas istorias nostras / Lassat totu fora s’ajanna / Ca custu sero nudatteru nos importat / Finzas chi sa manu tua istringet sa mia”

(We all have our stories / Leave your troubles at the door / Because tonight nothing else matters / Long as my hand is in yours)

It was a breath of fresh air to play live music and to know others were doing the same, somewhere around the corner, across the island, or on the continent. When I finished my set, I looked up at a group of people who gathered to listen, the lit sign of the closed shop behind them glowing above their heads like a halo.

“Grazie,” I heard someone say. I couldn’t see who was speaking, so looked up to a fourth floor balcony. A man in his early 20s waved at me. “Grazie,” he said again. We made eye contact. “De nudda,” I responded in Sardinian. You’re welcome. [2] [2] Special thanks to ethnomusicologists Marco Lutzu, Diego Pani, Ignazio Cadeddu, and Bastianu Pilosu for their assistance in the translation and interpretation of the songs discussed; to musician Antonio Pani for permission to share his song “Su Baballoti”; and to Radio Limbara for their permission to reprint their meme here. Gratzias!