How to Make Climate Change Feel Real

The year is 2018. The world’s leaders are gathered, yet again, to try to solve the crisis of climate change. But this time, the United Nations secretary-general is an Episcopal priest. And Russian President Vladimir Putin happens to be an executive business student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At one point, Putin begins yelling in English, with a Russian accent, when a protestor in a poncho arrives, leading a group of activists while carrying an acoustic guitar. Chaos ensues.

If you don’t recognize this piece of history, that’s because it was only a game. More specifically, it was one of two sessions of the World Climate Simulation that I sat in on as an anthropologist in the fall of 2018.

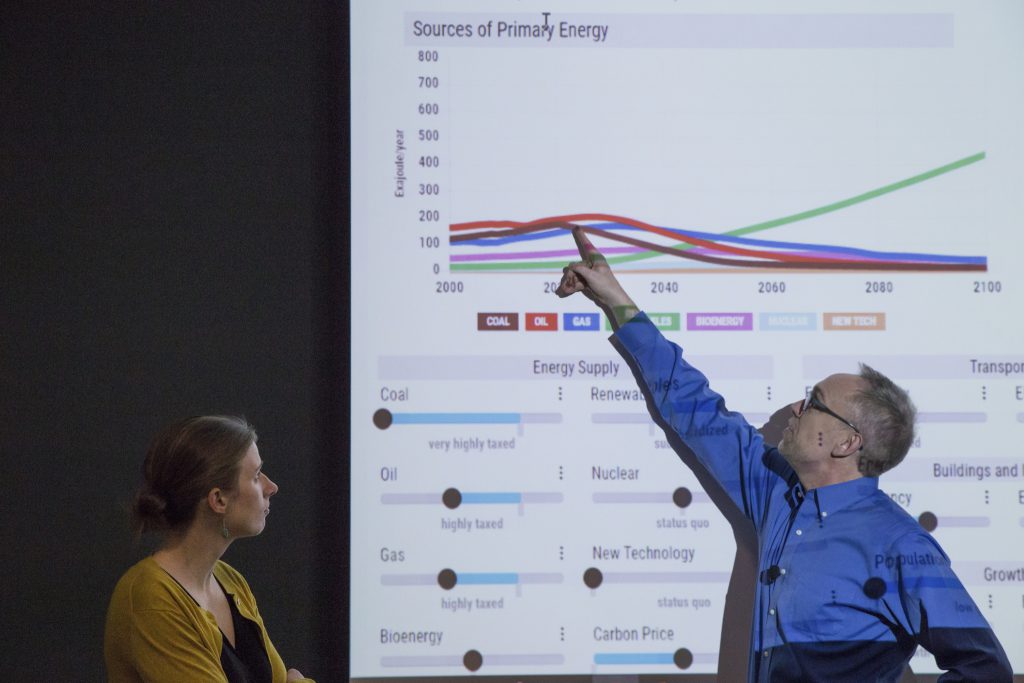

The World Climate Simulation game was created by Climate Interactive, a 16-person, U.S.-based nonprofit think tank. Designed for eight to 50 (but up to 500) participants, this experiential learning game is a role-playing exercise using one of Climate Interactive’s own innovative climate models: a simple, interactive computer model that can run on your laptop, simulating changes in global temperature, carbon emissions, or energy policy in literally one second.

Since it was launched 10 years ago, more than 66,000 people in over 90 countries have used World Climate and its model as educational experiences and decision-support tools. Participants have included everyone from high schoolers in Canada to nonprofits in Nigeria to actual American climate negotiators at the U.N.

Climate change is a unique problem—something that this game’s designers are attempting to address. The causes and effects of climate change are long-lasting and distant from one another. It is everywhere and nowhere at once, made up of global, long-term trends that play out locally in mostly imperceptible ways. Driven chiefly by certain human ways of life, its impacts will affect everyone—some more than others. People produce carbon emissions in the United States or the European Union, yet the effects are seen, much sooner and more intensely, in Bangladesh or Fiji. People produce emissions today, but it is our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who will deal with consequences like sea level rise and increasingly extreme weather. All of this makes effective climate action difficult to galvanize around, or even to imagine, for most people.

As an anthropologist, I have spent six years studying nongovernmental organizations that work at the crossroads of climate change science and politics. Over 15 months from 2017 to 2018, I conducted ethnographic research, both online and at real-life events, to investigate this crossroads in North America in organizations, including at Climate Interactive.

This experience taught me not only how innovative researchers and actors are helping to make abstract problems more concrete. It also taught me how those working in the domain between climate science and politics—like anthropologists—deploy the transformative power of experience.

That lesson is particularly relevant this April 22, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day—a pressing moment for reflection for many people who think and care about climate change.

Founded in 1970, today Earth Day is celebrated by more than 1 billion people each year to honor the health of the environment and celebrate positive relationships with the natural world. In the 1990s, Earth Day also laid the groundwork for early United Nations’ climate talks, including the 1992 U.N. Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit. The historic Paris climate accord was signed by 175 world leaders on Earth Day 2016.

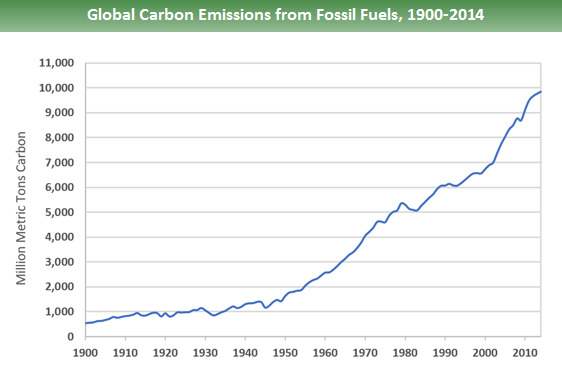

Yet, while Earth Day’s eco-friendly spirit has become more widespread, climate-changing carbon emissions have continued to rise: Since 1970, CO2 emissions have increased by nearly 90 percent, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). What’s more, half of the world’s CO2 emissions between 1750 and 2010 have occurred since 1970.

Most conversations about climate change discuss impacts “by 2100.” The goal of keeping the global temperature increase below 1.5 degrees Celsius or 2 degrees Celsius, for example, is in reference to the year 2100. This date is useful for several reasons: It sits within, but at the limits of, most people’s ability to picture the future. It is also a limit for which the international political and scientific communities can make accurate and meaningful predictions.

Hitting the targets set for 2100 will require urgent political, economic, and social changes—starting today. In order to have a fifty-fifty chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100, the IPCC wrote in its influential 2018 report, humanity will have to collectively reduce global carbon emissions by 45–50 percent from 2010 levels by 2030—just 10 years from now. This will take nothing less than a complete transformation of humanity’s global economic and energy systems.

How can humans grapple with the vast consequences of our collective action? How do we understand and act on the scale of the global climate? And where do we as individuals fit into solutions for a problem that is about so much more than individual consumers?

Such a transformation feels so big, with the underlying problems so intractable, it almost seems impossible. As Andrew Jones, a co-director and co-founder of Climate Interactive, put it in a podcast last year: “How do we sit with that as human beings? How do we sit with impossibility?”

Climate Interactive and organizations like it address these issues from different vantage points and, as I have written elsewhere, fulfill different roles in the space between science and politics. In our first lengthy interview of early 2018, Jones shared with me a question that has guided his career: “What are experiences that help people understand, viscerally, the long-term, distant impacts of their actions in ways that create new possibility?”

“The best thing I found to do that, in a scale that matters,” he told me, “are computer simulations—games around them or learning how to make decisions around them.”

Jones and his organization perform the dual roles of technology development along with science communication and education. Climate Interactive was founded on the idea that values and experiences, not information, are what really shape people’s perceptions and actions. As MIT Sloan School of Management business professor and Climate Interactive senior adviser John Sterman likes to say, “Research shows that showing people research doesn’t work.” For issues like climate change, telling people what to think or how to act doesn’t have an impact. Instead, tools like World Climate create opportunities for people to learn for themselves about the climatic, economic, and geopolitical systems that shape our world.

For example, Canadian high school teacher Kristen Simonson has used World Climate in her environmental science classes in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. She says the simulation helped her students experience the dynamics of the climate system for themselves. World Climate also gave her students a time and place apart, she says, to look at the world from a broader perspective, beyond a small town on the prairies. By inhabiting the role of emissaries from far-off countries for the weekslong project surrounding the game, students were freed from the standards of their community or their family’s values, she says, to form their own ideas and opinions.

For other users, World Climate motivates them to act. Oluwatosin Kolawole, the president of the Climate Aid Initiative in Nigeria, uses World Climate to inspire local-level climate action. The game has helped him promote tree-planting initiatives in his hometown of Lagos, a large city that is slowly falling into the ocean due to erosion from increasingly extreme weather and drought.

Research has shown that Climate Interactive’s tools and games are effective at helping people viscerally understand climate change. My own research suggests that’s because they are meaning-making, social, affective, and embodied experiences. In other words, they are quality communal experiences, full of emotion, involving not only the brain but the body—the kinds of engagements that scholars and practitioners in the field of science communication say are essential for getting complicated points across to diverse publics. They are often moving experiences for participants—opening up worlds of possibility through glimpses of other potential ways of being and living together.

Climate Interactive and anthropology have something in common: They both use experience to understand complex, alternative realities and to better understand our own. They are both intrigued by the possibility of an “other than”: the incredible but simple fact that things have been different in the past, are different now in some places on Earth, and can be different in the future.

As I write up the results of my research on Jones, Climate Interactive, and other organizations for my dissertation, I have come to understand that the possibility unearthed by such a simple idea—that another world is possible—is both a revelation and a boon for hope in these sometimes dark times.

Today it is hard to ignore the fact that the world is dealing with another complex, frightening, and systemic problem, thanks to the pandemic sweeping the planet and the political and social responses to the coronavirus. Like climate change, this is a problem that affects everyone, though some more than others, with nearly imperceptible progressions and delayed and distant causes and effects. And, like climate change, it invites us to imagine other ways of being. As Jones’ co-director and co-founder at Climate Interactive, Elizabeth Sawin, has recently noted, the pandemic gives us an opportunity to envision and enact more just, safer ways of living together.

The groups I study don’t have a magic spell to fix global crises, whether climate change or pandemics. As Jones likes to say, there is no silver bullet for solving climate change, but there is silver buckshot. In other words, many solutions are simultaneously needed.

People across the globe are already grappling with these problems and their solutions, as impossible as they seem. The folks at Climate Interactive, using their models and games to create transformative learning experiences, are just one example. Anthropology, too, attempts to connect the value of individual lives to systemic understandings with experience and empathy. Perhaps together we can catch a glimpse of where a more just, safer world is already visible, shining through the cracks in what we previously thought was possible. As we look from the 50th anniversary of Earth Day toward 2100 and beyond, I hope we can take with us this feeling of possibility.