For Chimps, Human Touch Can Hurt

The bruise on my bicep was starting to purple. Small, teeth-shaped scabs crusted over its center. While typing field notes, I stopped midsentence to poke the bruise and see if it still hurt. It did.

Being bitten was not what I expected when I traveled to Cameroon in 2015 for 18 months of dissertation research. During my fieldwork in chimpanzee sanctuaries, I would be bitten—multiple times—by Gnala. At a year old, Gnala (pronounced “Nya-la”) was the youngest chimp at the Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue (SYCR) when I arrived there.

While preparing to leave the U.S. for Cameroon, I helped name Gnala. The sanctuary had asked their Facebook followers to suggest names for a newly rescued chimp. She was tiny. Big ears framed a light-brown face, and her wide, honey-colored eyes made her seem perpetually surprised. I suggested Gnala, which means “sweetheart” in Zarma, a language I spoke while serving in the Peace Corps in Niger 10 years earlier. Gnala’s name soon became a running joke. Her biting, pinching, and hair pulling earned her the nickname “Little Devil.”

The SYCR, like more than a dozen other accredited primate sanctuaries in Africa, provides lifelong care for chimpanzees orphaned by the illegal pet, zoo, entertainment, and bushmeat trades. Orphaned chimpanzees that have been beaten by humans, isolated for long periods of time, or stuffed into boxes for transport and sale arrive at the sanctuary visibly terrified. Some scream or bang their heads against things, while others bite the caregivers who try to comfort them.

Gnala was different. By her second day, she enthusiastically sought human touch. Gnala solicited tickling like other chimps: presenting her back to the tickler, scrunching her shoulders up to her ears, and raising her hands as if to shield her neck from the almost unbearable pleasure of it all. When caregivers used chimpanzee gestures to signal the end of playtime, Gnala charged in for more, laughing, biting, and scratching with abandon.

In recent years, wildlife sanctuaries, conservation organizations, and animal rights groups have told the public to stop touching chimpanzees and other wild animals. National Geographic, PETA, and even Instagram draw explicit links between human touch and harm. They discourage wildlife enthusiasts from visiting “fake sanctuaries” that let tourists play with wild animals. Sanctuary accreditation organizations, such as the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA), can refuse to accredit facilities that allow visitors to touch primates. They say that visitor illness, easily communicated through touch, can kill a young chimpanzee. Moreover, this touch—even if it is playful—can harm chimps and other wild animals by igniting a desire for human interaction.

These organizations are trying to educate a public that seems largely unaware of the link between playful touch and harm. Somewhere between 3.6 and 6 million tourists visit wildlife tourist attractions (WTA) annually. In a 2015 study, zoologists at the University of Oxford analyzed visitor feedback on WTAs on the online review forum TripAdvisor. Around 80 percent of reviewers failed to identify problematic practices as harmful; many comments praised organizations that offer close encounters with wildlife. For a little money, tourists can snuggle a sloth, swim with a baby tiger, or even tickle a rambunctious little chimp.

How does any of this do harm? Gnala arrived at the SYCR wanting human touch. Would playing with (healthy) visitors really hurt her?

In my work, I found that our touch presents a conundrum when it comes to chimpanzees. Sanctuary staff must touch Gnala to help her. She needs frequent, reassuring contact to support her development. In this sense, human touch can help. But human touch outside of a real sanctuary—even if that touch is sweet—harms, and that harm cuts deep. It can spark a series of events that irrevocably change a wild animal and may even threaten her life.

When Gnala was just weeks old, a wealthy Cameroonian businessman bought her from a poacher. He gave her to his children as a pet. The man’s brother knew keeping a chimp was illegal in Cameroon, and he reported the situation to the sanctuary. When SYCR staff told Gnala’s owner he had to surrender her, he pleaded his case. His children loved Gnala. She had the run of the house, climbing on the couch and eating human food. She was a part of their family, he said. Nonetheless, authorities confiscated Gnala, and she became the 71st chimpanzee at the SYCR.

Sheri Speede, an American veterinarian from Mississippi, founded the sanctuary in 1999. Its mission is twofold: ensuring the welfare of rescued chimps and promoting species conservation by helping to stop poaching and the illegal chimpanzee trade.

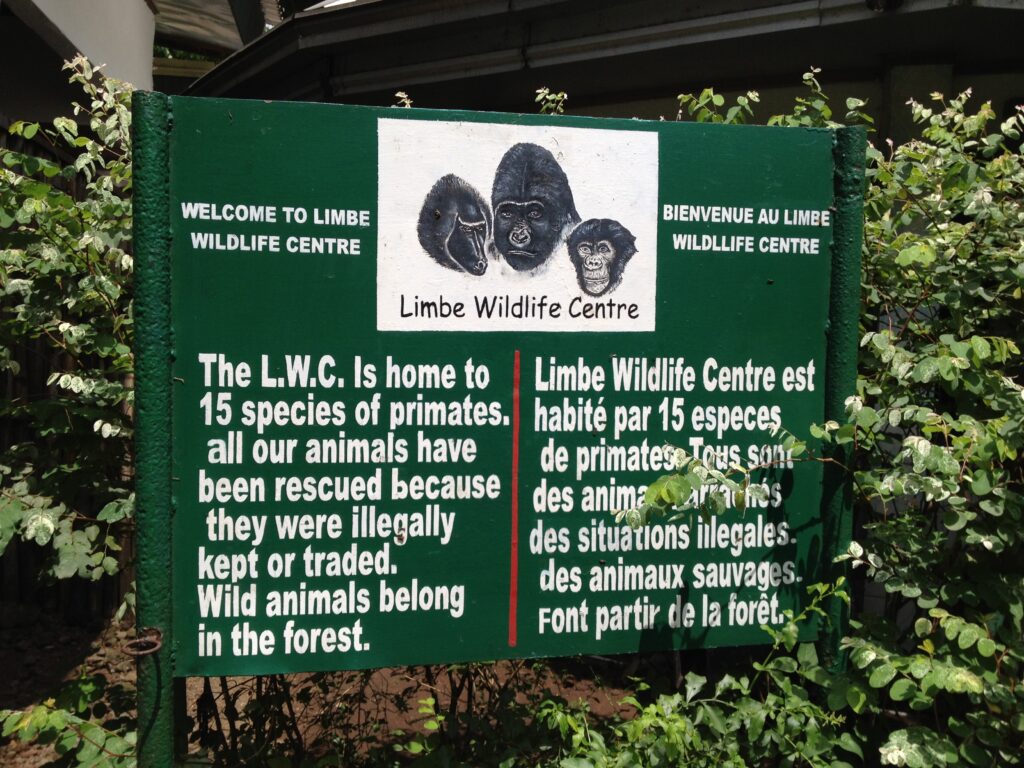

Throughout Africa, poachers and wildlife traffickers sell adult chimps as bushmeat. Captured infants may go as far as the Middle East, where demand for exotic pets is growing, or China, where zoo owners know a cute baby chimp will attract large crowds. By some estimates, people pay tens of thousands of dollars for individual infants. Experts say fewer than 200,000 chimpanzees remain in the wild. When officials arrest traffickers and poachers in Cameroon, the chimps they seize go to the SYCR or one of Cameroon’s other two accredited sanctuaries, Ape Action Africa or the Limbe Wildlife Center. These sanctuaries therefore play a vital role in the wildlife law enforcement chain and are critical to conservation.

The SYCR is committed to chimpanzee welfare. They promise to provide lifelong care for orphaned chimps (who can live for up to 60 years) because reintroducing them to the wild is not always possible. Managers, staff, and volunteers from Cameroon, Europe, North America, and Australasia try to replicate forest living as best they can. The sanctuary sits on 225 acres of the Mbargue Forest. Adult chimps spend their days climbing tall trees and foraging for wild ginger in large forest enclosures, which range in size from 1 to 20 acres. The chimps eat tropical fruits and vegetables bought from local farmers, and sleep in large night cages for protection from poachers. Chimps and humans use chimpanzee alarm calls to communicate danger when they see cobras, vipers, or green mambas, one of the world’s deadliest snakes. Compared to the fate that awaited them, chimps at the SYCR lead a very good life.

When I met Gnala in 2015, she and a 1.5-year-old female named Kimbang spent their days in the forest, away from visitors. The pair stayed close to Henriette, their full-time Cameroonian caregiver. Henriette encouraged Gnala and Kimbang to do “chimp things” such as digging, climbing, and wrestling with each other.

I became one of Gnala’s volunteer caregivers because, as a cultural anthropologist, I gather data by participating in what I study. I was there to understand “care.” What is it for one species to care for and about another? How do humans from different countries, religions, languages—from different moral worlds—negotiate competing ideas about what makes for good care? To get an embodied sense of what it is like to care for infant chimps, I tended Gnala and Kimbang on Henriette’s days off.

Before I met Gnala and Kimbang, Lisa (a pseudonym), an assistant manager from Belgium, explained to me that we were to provide reassurance and discipline to the infants. Comforting them when they were frightened would help them learn to trust. Teaching them to recognize “no,” by redirecting their attention and hooting at them when they did wrong, would give them a sense of limits. To hoot like adult chimps, we dropped our voices a few octaves and grunted a loud, fast, “HOO!” Lisa stressed that understanding boundaries would help keep Gnala and Kimbang safer when it came time to integrate them with adult chimps.

Gnala and I got by with my redirection and hooting for several months. When she bit my shoelaces, I feigned interest in nearby millipedes or butterflies to redirect her attention elsewhere. I hooted at her for pinching me when I tried to disengage from play. Her pinches hurt, and her scratches stung, but Gnala was easy to forgive—until the day redirection and hooting stopped working. That was the day I began to question my own assumptions about harm and human touch.

Gnala and Kimbang finish half a papaya, and Kimbang springs up a tree. Gnala stays perched on my lap. It is the rainy season in 2015, and I have been working with Gnala for five months. The humidity makes it impossible to dry clothes, so my pants are damp and smell like mold. I wipe Gnala’s sticky hands with a leaf, but she is focused on something just above me. All at once, she launches herself at my face and grabs the knot of hair piled on top of my head. She hangs, one-handed, from my hair. My eyes water, and my scalp burns. I grab her at the waist to support her weight and relieve pressure. I hoot my best baritone hoot and bark her name, “GNALA!”

All five of her long fingers are threaded through my hair. I find two and try to pry them open. No dice. I hoot again, but she stays put. And then I laugh because I do not know what else to do. I cannot call over the radio and ask someone to come get the smallest chimp in the sanctuary off my head. While we sit there, I review my options. Chimp hoots are not cutting it. I wonder, what if I go more chimp? What if I bite her?

Kimbang bites Gnala in two ways. She uses what I think of as “blood bites,” which break skin and make Gnala scream, and “snap bites,” where she takes Gnala’s skin between her teeth, pulls it hard, and then releases it. I imagine that this rubber band motion feels like a hard pinch to Gnala, and it usually stops her from doing whatever she is doing. The snap bite is probably my best bet.

I try a final time to peel Gnala’s fingers open, and I hoot once more to make sure I exhaust all my options. Nothing happens, so I take a soft chunk of hairy forearm between my teeth, inhale, and bare down.

She does not move. I apply more pressure. Nothing.

Chimps are said to have a higher pain tolerance than humans. If I bite her harder—if I’m a little more chimp—she will let go. I can do this, I tell myself. I try again, then stop.

Although human jaws are strong, and my ape self is capable of biting her, my human self is not. The pressure I need to use for a chimpanzee snap bite would break human skin. I cannot make myself say “no” like a chimp would. We sit like that until she finally releases her grip, drops into my lap, then darts off to examine the broken hairs she has made away with.

I often thought about harm and human touch throughout my remaining 14 months in Cameroon. I asked myself what kind of person bites a baby chimpanzee and how did we arrive at that moment: Gnala with her baby vise grip and me at a complete loss over what to do.

During interviews, I began asking directors, managers, staff, and volunteers if we should make our touch a little more chimp. Are we hurting infants by not disciplining them like chimpanzees would? When I asked Speede, she answered: “That could work, while they’re young, but as they get stronger than us we’d have to be really brutal to keep that up. … We wouldn’t do that because we wouldn’t want them to be scared of us.”

By the time I returned to Cameroon in 2018, 4-year-old Gnala had become too strong for Henriette to handle in the forest. Gnala’s strength, climbing ability, and foraging skills meant she was ready to be “adopted” by an adult female chimp. The managers identified Jantan to care for Gnala and Kimbang as if they were her own.

The adoption went smoothly. Jantan and Gnala now sleep side by side, and Gnala rides on her back around their forest enclosure. The threesome spends their time climbing, napping, and playing chase.

This time is a critical learning period for Gnala and Kimbang. Next year, they will be integrated into a larger forest enclosure with adult chimpanzees. Although extremely rare, infants can be injured or even killed during integrations if they do not adhere to chimpanzee social norms. Infants learn about nurturance, dominance, and chimp politics largely through observation. They see how grooming others can solidify shifting alliances. They witness aggression when males injure one another while vying for the position of alpha and when their group kills outsider chimps encroaching on their territory.

Sanctuary staff often say that chimps like Gnala are the hardest to integrate, because chimps used in tourist attractions or kept as pets are largely ignorant of the role of aggression in chimpanzee society. The infants that know human touch—how human hands hold and human fingers tickle—are often unfamiliar with chimp social boundaries. For Gnala, that ignorance could be dangerous.

It’s early evening in April 2018, and Gnala stares at me from within the cage area where she sleeps. As I wait for her to reach her hand through the bars so I can drop an avocado into it, she extends her palm out farther than I expect. Gnala manages to flip her wrist and quickly dig her nails down deep into the back of my hand. “Owwww! Gnala!” I mumble as I snatch my hand back.

Gnala is bigger now—though she is still the smallest chimp in the sanctuary. She often stands on two legs and walks bipedally around the enclosure. Her face is darker, more of an ash brown.

Gnala positions herself a few feet above me. She clings to the cage bars and expertly waits until I look toward Kimbang. Gnala aims and drops the avocado I gave her on my head. I stand up, brush the dirt off my pants, and finally look down at my hand. A scratch or scrape itself is not dangerous unless it becomes infected, but it hurts.

When she scratched me, she drew blood.

Today, when volunteers come to the SYCR, managers warn them about how dangerous Gnala is. Do not be deceived by her size; small does not equal safe. Staff say Gnala may grow up to be the most aggressive chimp in the sanctuary. Her regular attempts to bite and scratch the humans caring for her is unusual when compared to the behavior of other chimps at her age. Their aggression, unlike Gnala’s, could often be explained by context: If an infant perceived a human’s actions as violating their boundaries, the chimp may bite. Gnala’s behavior is much less predictable. However, Gnala’s aggression toward humans, in and of itself, is not the problem. It is her sense of boundaries, and how untested they are, that is disquieting. Jantan indulges Gnala, as mother chimpanzees often do, which leaves staff with a lingering question: When she faces new adult chimpanzees with firm boundaries, will Gnala know when to stop?

For chimps like Gnala, human touch set a particular kind of harm in motion. It fractured her world, dividing her experience into a before and an after. In her short before, when she was a newborn with her chimp family in the forest, her body matched up to those around her. She touched and was touched by bodies that aligned with hers. She exercised her clinging reflexes days after birth and later would have tested her power in wrestling matches with her siblings. Their strength would have accommodated hers and helped her grow her own. But then time stopped.

Poachers forced Gnala into human touch. When a chimpanzee group flees poachers and a mother is shot mid-flight, she goes down with her infant. The infant’s grip is so tight that poachers must pry her from her mother’s body. Given this fact, Gnala’s first contact with human hands would have likely been violent.

When the Cameroonian father bought her for his children, she met a human touch that was different in tone. Children’s hands reached for her as they would a human baby or a hairy little doll. Being carried upright against a human chest would have been a mismatch for Gnala’s long arms. Her muscles would not fully develop. Over time, other incongruities would have appeared. Gnala’s mounting strength would quickly surpass that of the children’s. Her agility would make her hard to catch, tough to hold, and impossible to restrain.

Compared with the touch Gnala’s chimp family would have provided, the children’s touch would have been too soft and gentle. When she became too chimp for the children, their father could have kept her in a cage, dumped her somewhere, or sold her as bushmeat, all likely outcomes for chimps who have outgrown their pet status.

Gnala was not abused in the conventional sense, like many captive wild animals are. Her teeth were not pulled out with pliers to prevent her from biting. To our knowledge, she was not beaten. But she was harmed.

Although Gnala is one of the lucky orphans that made it to a sanctuary where humans encourage her chimpness, there is always a tipping point. As she ages, human efforts to emulate her chimp family will not be enough. Our muscles will not win in a tug of war. Our hands will be too small, our skin too sensitive. Our touch, and our ability to be touched by Gnala, will be too weak. As Speede pointed out, we would have to compensate by going much further than biting.

Rachel Hogan, a conservationist originally from the U.K., directs Ape Action Africa (AAA), the largest primate sanctuary in Cameroon. At the close of an interview, Hogan told me, “The truth is, we aren’t chimps. We aren’t really their mothers. We can’t give them what their mothers could have. Their mothers are gone.”

Hogan’s point gets to the heart of harm. Sanctuaries try to transition infants from human care to living with other chimpanzees as soon as possible, because human touch is not enough for a chimp. We give Gnala the best life we can. We use her vocalizations. We dig in the dirt next to her. We move through the forest with her on our backs. But our touch will always fall short.

Her life is irrevocably different due to human touch; Gnala must reconcile the human with the chimp. Sanctuary staff have tried to prepare her. They set boundaries with her and integrated Gnala with Jantan when she hit her tipping point. Soon she will enter an adult group. As much as humans tried to prepare her, and as much as Jantan will try to defend her, Gnala must find her way on her own. [1] [1] Postscript: If you want to watch Gnala grow and follow her progress as she is integrated into her new adult chimp group, you can follow the SYCR on social media or check out Gnala’s adoption page on the SYCR website.