Carbon Farmers Work to Clean Up the World’s Mess

It was a bright afternoon in March of 2011 when I met Pedro (a pseudonym) on his organic farm in the mountains of Costa Rica, north of San José. I was there to do research on changing agricultural practices in the country. As we walked around his land, he showed me his greenhouses where lettuce, potatoes, and peppers grew. The warm air smelled earthy and sweet.

Outside, there were curving rows of carrots planted in the dark earth. He pulled some out and, after washing off clumps of dirt that were clinging to the roots, handed them to me to taste. They were different colors, and each had its own flavor—the yellow was sweeter than the white.

There was a slight breeze. The rolling landscape was vibrant and green. And there was carbon in the ground. Pedro knew it was there, and he was talking about it because of climate change.

Noting that climate change was causing droughts and floods throughout the world, Pedro told me that he and members of his organic cooperative were working, on their farms, to “mitigate the problems of carbon.” They were using a series of agricultural practices that have gained increasing global attention in recent years as a potential climate solution. The practices themselves are not new. But the reasons why people are paying attention have changed.

The approach is sometimes called carbon farming. It’s based on the principle that plants take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere during photosynthesis. While much of that carbon stays in the plants themselves, some of it also travels into the soil. And when plants die, more carbon is added to the ground as organic material. The idea is that some agricultural practices—like planting cover crops instead of leaving soil exposed, using compost instead of synthetic chemicals, and planting a diversity of crops instead of a monoculture—can help to keep more carbon out of the atmosphere than their alternatives.

As the journalist Moises Velasquez-Manoff recently wrote in The New York Times, “if we change how we treat [agricultural] land, we could turn huge areas of the earth’s surface into a carbon sponge.” This concept is increasingly entering mainstream conversations, as international development organizations, governments, and farmers throughout the world are talking about agriculture in different ways.

Back in 2011, Pedro told me that organic agriculture is well-suited to the task of addressing climate change. The key to this process, he said, is working with soil. To do this, Pedro and other members of his cooperative used a variety of techniques. For example, instead of planting the same crop in the same place year after year, they rotated them, so that where you planted lettuce one year, another year you’d plant beets, he said. And instead of using synthetic chemicals to boost soil fertility, they used organic alternatives.

As a result, their soil was healthy and alive, and Pedro said studies suggested that their cooperative was able to “capture 20,000 tons of carbon” that year, “more or less.”

While some farms like Pedro’s are certified organic, diverse, and small-scale, that convergence does not always happen. Organic agriculture is not always as idyllic as consumers might imagine: In some places, crops are grown in extensive monocultures. And many of the agricultural practices associated with carbon farming, like crop rotation, are not necessarily organic.

That said, in Costa Rica organic agriculture is recognized in a national law for its role in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. And the global search for climate change solutions has influenced the ways that some farmers, NGOs, and government officials speak about the value of organic agriculture in the country.

It’s been seven years since I met Pedro on his farm, and I still remember the taste of those carrots, the warm earthy air in Pedro’s greenhouses, and the way that carbon allowed him to connect his work to a global environmental endeavor.

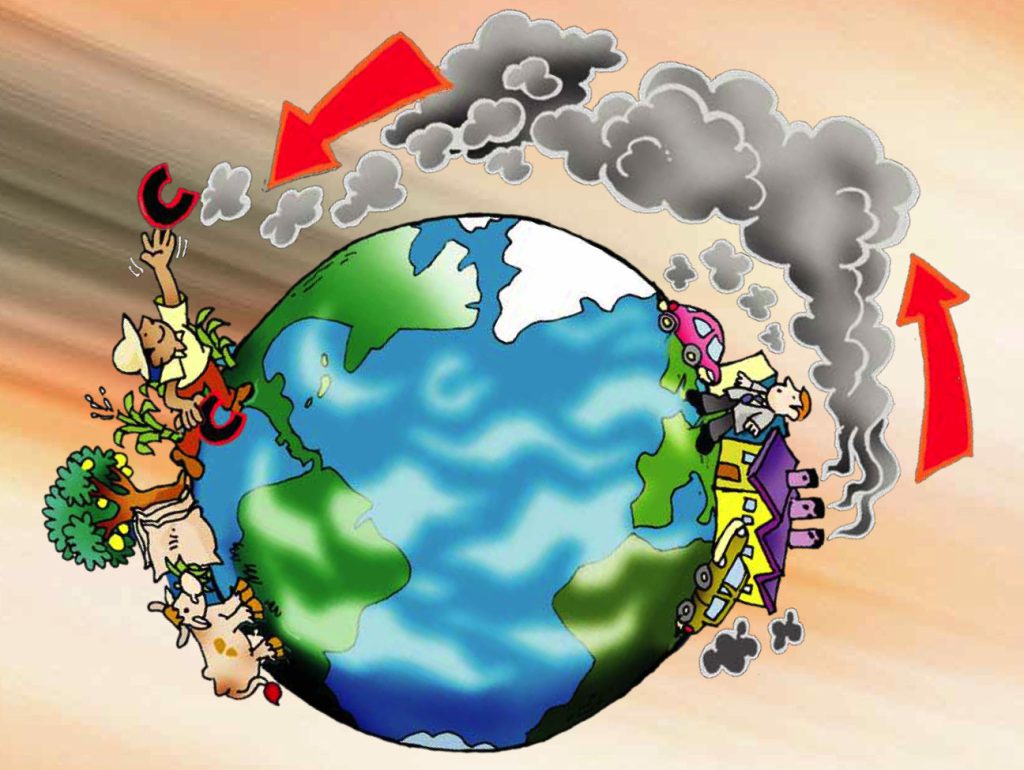

But global interconnections can be hard to see. Perhaps that’s why I am drawn to an illustration from a pamphlet that describes research on climate change and sustainable agriculture. It was published by a Costa Rican NGO called CEDECO, which studies and promotes environmental approaches to agriculture throughout Latin America.

Beneath the title, there is an illustration of a globe. It depicts two different places, connected by climate change. In the north there is a man wearing a suit, his feet planted firmly in Europe. He stands near cars and a building that is emitting gray plumes of smoke. Red arrows show the smoke flowing around the globe from north to south.

Meanwhile, in Latin America, a smiling farmer reaches his hand up into the sky to collect the carbon that came from Europe. The farmer’s happiness seems to reflect the trees and plants around him—and the work he is performing, as he takes carbon out of the atmosphere and puts it into the ground. In recognition of that work, CEDECO has implemented programs that help “climate farmers” receive benefits for their contributions to mitigating global carbon emissions.

The illustration shows one facet of global interconnection—and possibility—in the midst of climate change. But as it also shows, the “problem of carbon” did not begin in Costa Rica. And for farmers, the challenges caused by climate change will only grow more intense as time goes on. So as we search for potential climate change solutions, we should not lose sight of the nations, corporations, and lifestyles that continue to make climate change worse.

Farmers already feed the world. The rest of us still need to do our part.