Gathering Firewood—and Redefining Land Stewardship—at Bears Ears

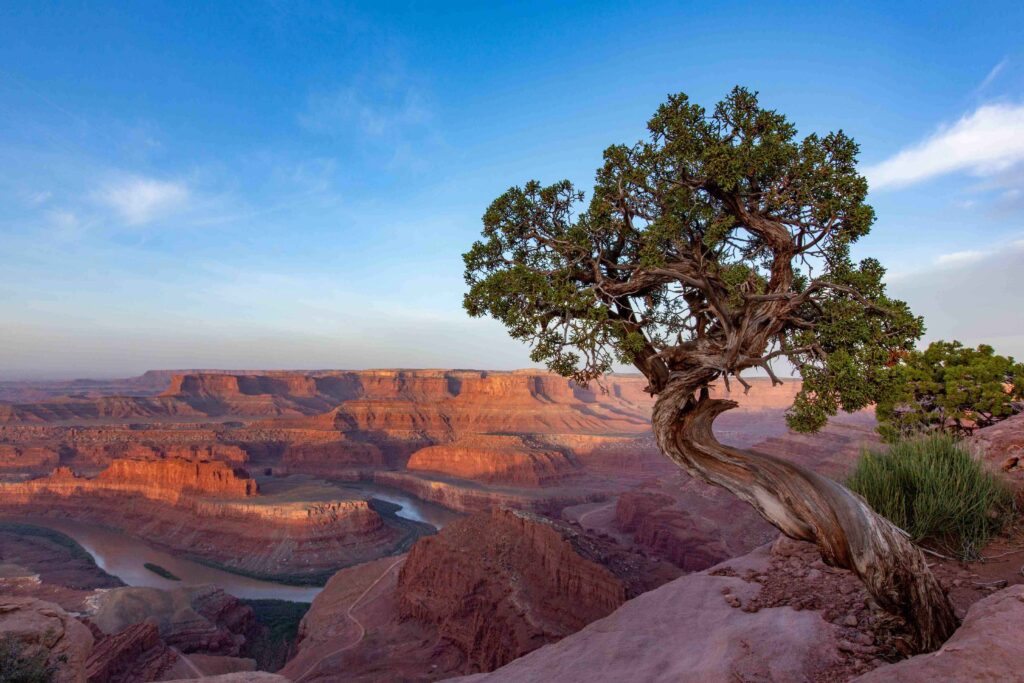

As our team of researchers drove southeast through Utah toward Bears Ears National Monument, changes in the landscape unfolded around us. The skyscrapers of Salt Lake City gave way to small towns surrounded by trees and mountains. When we arrived at our campsite in a remote canyon bottom in San Juan County, the prominent twin buttes that give the area its name towered nearby, and we were met with immense cottonwoods and an expansive plateau covered by pinyon and juniper trees.

For our group from the University of Utah, the surrounding trees were a visceral respite from the city. For Diné (“the people” in Navajo), whose lives are embedded in this place, these trees mean much more.

For many Indigenous peoples, gathering firewood is central to their livelihoods, identities, and survival. On some parts of tribal lands in the U.S. Four Corners region—where present-day Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet—around 90 percent of people surveyed depend on wood harvested from nearby forests for ceremonial use, to generate household energy, and for building materials. Many Diné people, for example, live in remote areas where basic utilities, including clean water and electricity, are inaccessible. In addition to providing needed heat, wood-hauling practices are an essential part of cultural identity.

However, Indigenous practices do not always fit neatly with U.S. conservation techniques because of the settler-colonial values that underpin environmental and land management policies. These values rest on the belief that humans are apart from natural systems rather than a part of these systems, creating tensions for federal land managers and residents.

As a home and sacred land to Indigenous people who lived on the landscape well before U.S. federal agencies existed, the Bears Ears area holds enduring cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance to the tribes of the region. Since European contact, Indigenous people have struggled to protect the lands—which outsiders often describe as a vast “outdoor museum”—from vandalism and desecration, organizing through formal and informal channels for the protection of the Bears Ears landscape.

In 2016, the area was granted federal status as Bears Ears National Monument (BENM). The BENM encompasses 1.36 million acres and protects against the development of extractive industries such as oil, gas, and uranium.

Currently, a new co-management plan—the first of its kind—is underway between the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, a consortium of the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and Ute Indian Tribe. The co-management plan recognizes the deep cultural legacies of Indigenous peoples and establishes a legal basis for ceremonial and traditional practices such as gathering medicines, food, and firewood.

It’s too early to tell the overall impacts of this plan’s implementation. But our research on firewood gathering by Diné people shows the federal government can do more to ensure the promises of equitable co-management. The BENM is now at a critical point for reckoning with how the expertise of Indigenous people can authentically guide relationships with land.

WOOD HAULING AS ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

Folks from the northern Navajo Nation in Utah and Arizona often refer to gathering firewood as the “wood-hauling” life.

For those with deep knowledge of the forest, firewood collection is an ecological act. Wood haulers ensure the longevity of the forest by avoiding harvesting trees that are still part of the living system. Those practicing traditional knowledge only select trees that have died and are not occupied by other forms of life such as insects and birds. The wood harvests are then shared among Diné households, where food and tea are often prepared on woodburning stoves. From the largest pinyon and juniper down to the living soil crusts, everything is connected, including the people.

Indigenous communities in the Four Corners region say that maintaining these critical connections to firewood is often complicated by U.S. management policies that limit their access. Since 2015, our research team has been part of a collaborative project that’s trying to better understand the significance and challenges of wood-hauling practices for Indigenous communities. This project brings together Native American wood haulers, researchers from the University of Utah, and the Indigenous-led nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah (UDB), whose mission is to protect and preserve culture, traditions, language, and ancestral lands.

With permissions and additional guidance from Navajo Nation, our research team has helped with firewood harvest and interviewed and surveyed wood haulers. Our co-authors include an undergraduate student (Rachel), a graduate student (Samuel), the former communications director of UDB (Jesse, Ute Indian Tribe), an anthropologist (Kate), and an environmental studies scholar (Adrienne). Together, we’ve collaborated on this larger project by seeking approaches based in environmental justice.

Why environmental justice? The framework goes beyond simply mapping or measuring rates of pollution, deforestation, or other environmental harms, as other conservation science approaches tend to do. Instead, it looks broadly at history, politics, ideologies, and other factors to explain how these harms emerge and get perpetuated across time and space.

Understanding land management in the Bears Ears area from an environmental justice perspective means considering, for instance, how the formation of reservations in the 19th century dislocated both people and ecological relationships. Policies that encouraged Euro-Americans to “settle” on lands occupied by Indigenous groups also played a role, setting the stage for “settlers” to privatize and commodify the land that Diné and other Native American identities are based on.

An environmental justice framework also helps highlight wood hauling as an issue of tribal sovereignty and self-determination. This calls attention to the idea that tribes, as sovereign nations, should maintain control of their energy sovereignty today and in the future, whether it’s based on nonrenewables, solar, wind, wood hauling, or a combination of sources.

THE CHALLENGES OF CO-MANAGEMENT

The co-management plan for the BENM acknowledges tensions between Indigenous and settler land management paradigms. A number of different groups are engaged in this process, including federal, state, and local government agencies; conservation organizations; and tribes. In our research, we’ve found that between and within each of these groups, people often hold dynamic, diverse perspectives on land management, energy sovereignty, and traditional lifeways. Although these individuals and groups endeavor to work together, they frequently frame land management and conservation in profoundly different ways, leading to conflicts.

For example, the USFS and BLM are guided by federal legislation that directs their representatives to manage lands using the language of “multiple use” and “sustained yield” of resources. According to a 1960 law, this means resources present on the land shall be extracted and “utilized in the combination that will best meet the needs of the American people.” In many ways, ecologically driven traditional firewood harvest practices are inherently in keeping with this law. However, assessments of what qualifies as “multiple use” are largely made by non-Indigenous and nonlocal decision-makers who tend to value extractive commodification, such as grazing or recreation access, over practices that sustain ecological relationships.

The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition is legally bound by the multiple-use paradigm, which makes it difficult to protect fragile cultural sites and systems, including wood hauling. These legal requirements also set certain timelines for policy changes that demand a pace of action that runs counter to the slower dialogue inherent in many Indigenous decision-making processes.

Limited resources also make it difficult for Indigenous communities and leaders to fully participate in formal land management processes. Recent legislation has responded to this latter issue by centering tribal participation in federal research grants and funding reliable internet access. But Indigenous communities and leaders are still far from being fully supported to be guiding voices at the table of land management decision making.

For Diné wood haulers, this situation is acute. A major point of contention lies in access to the lands protected by the BENM. In our interviews, wood haulers shared how the BLM had created new barriers to entry in an area designated as a “Wilderness Study” zone. One Diné elder told us, “They’re trying to close up all that area where we get woods. They’re trying to fence it in.” He added, “In some places, where we had made roads to pick up the trees, they put signs up there that say, ‘No vehicle allowed beyond this point.’”

These tensions point to a fundamental disconnect in understandings of how humans and landscapes are connected. The same Diné elder continued, “We’re always wondering what’s happening beyond that boundary. What’s going on back there to have that blocked off? Or is it just a stake in the mud to keep Natives out?”

When one group of co-managers considers conservation of “wilderness” as devoid of certain kinds of human impacts in order to protect an imagined “pristine” status, and the other sees human activity as an integral element of conservation, skepticism and distrust are bound to occur.

Another point of contention is over the BLM’s required permits for firewood gathering. A permit for each cord of wood—around one stacked truckload—ranges between US$4 and US$20, depending on the tree species. Beyond the direct costs, obtaining the permits requires time and resources. For example, permits used to be available only through centralized government offices, which were often prohibitively far away and off Navajo Nation. One Diné interviewee, who lived in Monument Valley, described having to travel to Monticello, 94 miles away, to get a permit. For some people, he explained, “getting [auto] insurance and [license] plates up to date” added to these challenges.

Currently, permits are available to purchase online, but many Indigenous community members lack sufficient access to the resources needed to make online payments, download, and print files.

The BLM has instituted pilot programs in an attempt to increase access to permits for tribal members. However, none have yet succeeded due to a combination of cultural, economic, and institutional barriers. This situation exacerbates divides between wood haulers and law enforcement, who sometimes issue costly citations to people who do not abide by the permit regulations.

“We don’t want to get stopped without a permit,” one Diné interviewee told us.

From the standpoint of the USFS and BLM, these permits are a necessary system of accounting and managing how much wood is gathered and from where. From the standpoint of Diné wood haulers, these permits exemplify the ways in which their Traditional Ecological relationships are being complicated by federal land managers.

ENSURING TRIBAL SOVEREIGNTY

From an environmental justice–informed perspective, the current co-management plan still leaves the needs of Diné wood haulers largely unmet, even though the BENM is intended to safeguard the cultural values of the landscape.

Looking critically at the ways environmental injustice has been constructed and is maintained has allowed our research team to better understand the power dynamics at play in managing the BENM. We believe requiring tribal members to navigate federal and state bureaucratic structures for firewood access diminishes their sovereignty. The tribes, as sovereign nations, should be leading the creation and maintenance of policies within the monument that affect their energy futures and connections to the landscape, including the rules around wood hauling.

As the process of co-management continues to unfold at the BENM, federal land managers must better uphold the promises of tribal sovereignty. That means acknowledging different worldviews and putting in place structures that truly empower tribes to access and share power equitably.

Research within anthropology and related fields has found that human and ecological communities are often healthier where Indigenous conservation knowledges are practiced. As managers of federally protected lands in the U.S. seek to incorporate the voices and priorities of Indigenous communities, they must take these lessons to heart and recognize the benefits of applied Indigenous knowledge to steward land. For locals and visitors alike, the BENM can be a place that showcases forms of stewardship that sustain living communities and dynamic landscapes into the future.