The Anthropology Professor in an Amazon Warehouse

My first day of work in an Amazon warehouse I was nervous.

I was beginning undercover anthropology fieldwork—and worried about being found out. Plus, I’d read horror stories about soul-crushing work demands inside the company’s giant facilities.

I’m a longtime Amazon shopper. But I’ve also felt guilt about patronizing a company accused of putting local bookstores out of business, underpaying its taxes, and treating workers badly. A coalition of anti-Amazon groups called Athena wants us to kick the habit. Was I bad for using?

In November of 2021, I decided to get a job at Amazon to see what it was really like. I’m still employed there now, a year and a half later. The work itself turned out not to be as hellish as I’d feared. And like many of my co-workers, I do not much mind and sometimes even enjoy it.

It’s the crummy pay that’s the big existential problem for Amazon’s hundreds of thousands of warehouse workers.

Although no worse and sometimes better than what other companies offer, the US$15.50 starting wage at my facility is nowhere near enough to live on. There’s little vacation time, no year-end bonuses, and nickel and dime raises. Many Amazon workers are stuck trying to live from paycheck to paycheck.

“It’s a trillion-dollar company,” a friend at my facility politely explained. “They could do better.”

AN OUTSIDER’S VIEW

Amazon’s rise from an online book business based in a garage to corporate behemoth is the stuff of modern mythology. Founder Jeff Bezos, the great prophet of e-commerce, always intended to grow his company into an “Everything Store” as vast as the great river after which he named it. Bezos relentlessly undersold competitors to grease the flywheel of lower prices, better selection, and more customers.

The profits made Bezos into one of the world’s richest people with a net worth of more than US$125 billion dollars. He flits around to Hollywood galas and sails the seas in a US$500 million megayacht. And he ventured into space in a rocket that bore a disconcerting resemblance to a giant sex toy.

Nowadays Amazon delivers almost 2 million packages a day. Like Google, Meta, and the rest of the Big Tech “algocracy,” it tracks users by the gigabyte a second. It knows that we shoppers want socks emblazoned with flying pigs or a new milk frother before we do ourselves. Plenty of people order necessities like shampoo and razors too.

A mouse click sets in motion the scanning, packing, loading, and delivery that spews packages onto doorsteps like a globe-spanning Rube Goldberg machine.

Though most people know Amazon for its deliveries, the company’s biggest money maker is Amazon Web Services, the world’s largest cloud service. And Amazon’s portfolio of subsidiary holdings includes Whole Foods, MGM, and Zappos.

Despite its ubiquity, Amazon remains a dark mirror. Like other tech giants, it knows everything about its shoppers—but we, very little about it. A scattered field of Amazon studies has emerged in recent years, including work by anthropologists, geographers, and economists. Journalists have written books such as Jessica Bruder’s poignant Nomadland—later an award-winning film—about the travails of older Americans laboring in Amazon warehouses.

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, I began wondering about Amazon when, like many others, I found myself manically ordering more than usual. That led me to teach a university course called “Amazon and the Cybereconomy” and to form a team called the Amazon Research Project to interview dozens of Amazon workers. Then I took the warehouse job to join in and observe, as we anthropologists do.

“Will you be OK?” asked a worried student when I was hired. We had been reading about Amazon and its sins all semester.

AN INSIDER’S VIEW

Not far from the Raleigh-Durham International Airport in North Carolina, my anonymous-looking facility is a sort center, a midpoint in the Amazon supply chain. Each day, we unload tens of thousands of packages that arrive already packed from one of the company’s mega-size fulfillment centers. They cascade down chutes like cardboard waterfalls onto conveyor belts for us to scan onto wood pallets and into metal carts.

Everyone hates kitty litter because it’s heavy, leaks, and mucks up the conveyor belt.

Once we’ve finished sorting, we wrangle everything onto big trucks backed into the loading dock. They transport the vitamins, cutlery, croquet sets, portable chargers, and backpacking stoves to delivery stations, where vans then ferry the goods to doorsteps.

I was sore for the first few days, but I’ve gotten used to it. It’s nice exerting my body rather than only my mind as I do at the university. And I like working with others to get a big job done—even if it mostly serves to pay off Bezos’ next extravagant toy.

Like me, some workers do not mind the exercise. “It’s like getting paid to go to the gym,” jokes Jacob (a pseudonym), one of my friends at our facility. As someone who is blind, he was impressed that Amazon recruited at a career fair for people with disabilities. But he has to commute by bus. It drops him off a half mile from the warehouse along a dangerously busy road.

Our human resources department has not yet provided Jacob with promised Lyft vouchers for him and others who need them to get to work.

THE AMAZON HIERARCHY

Sort center workers are mostly part time, and almost everyone has a second job to try to make ends meet: cashier at Dollar General, school cafeteria worker, bartender. One co-worker gives raga and sitar lessons at his daughter’s classical Indian music academy.

I soon realized that my fears about being outed were groundless. It’s been debated whether we anthropologists may sometimes justifiably employ false pretenses, for example, pretending to be a doctor to get inside an illegal organ transplant clinic. But I never had to fake anything, and I’m not even undercover: I’ve told many of my co-workers and managers that I’m a researcher working at Amazon to learn more about it. Some call me “prof.”

Amazon is far from the multicultural meritocracy it styles itself to be. To the contrary, the company exhibits what political theorist Cedric Robinson famously called “racial capitalism.” It gets Whiter the higher you go up in the company, with people of color overrepresented in the lower ranks. Our facility is majority young and Black, although quite diverse—younger and older people; those who are White and Latinx; women, men, and nonbinary people; formerly incarcerated individuals; people who are deaf and those who are autistic; and migrants from India, Iran, and all over Africa.

We all get along pretty well. One of the few things that can get you fired is getting aggressive, such as a friend of mine who was escorted out for threatening to knife a co-worker who’d accused her of slacking on the job.

Our supervisors are mostly nice, hardworking, and in their 20s and 30s. They don’t earn much more than we lowly workers, or “Associates” as Amazon euphemizes us. Although supervisors occasionally check our scan rates, nobody gets admonished much—unless they spend too long scrolling TikTok on the toilet. It’s always a scramble just to get the trucks loaded.

One of my younger co-workers detested his previous job at Chick-fil-A because of spattering hot grease and customers by the busload. He describes Amazon as a “pretty nice job,” albeit not for the long-term. Most Amazonians hope to move onto something higher-paying or to turn a side hustle into their own business.

STARVATION WAGES

Conditions vary from facility to facility. At the giant RDU1 Fulfillment Center just south of Raleigh, quite a few workers complain about favoritism, incompetent managers, and overheating in the building. That Amazon caps wages there at US$18.40 no matter your seniority especially irritates the longer-serving workers. Most RDU1-ers work four 11-hour shifts a week.

According to the MIT Living Wage Calculator, the minimum living wage for an adult with a child in the Raleigh area is US$38.93 an hour. No Amazon worker there makes even half that.

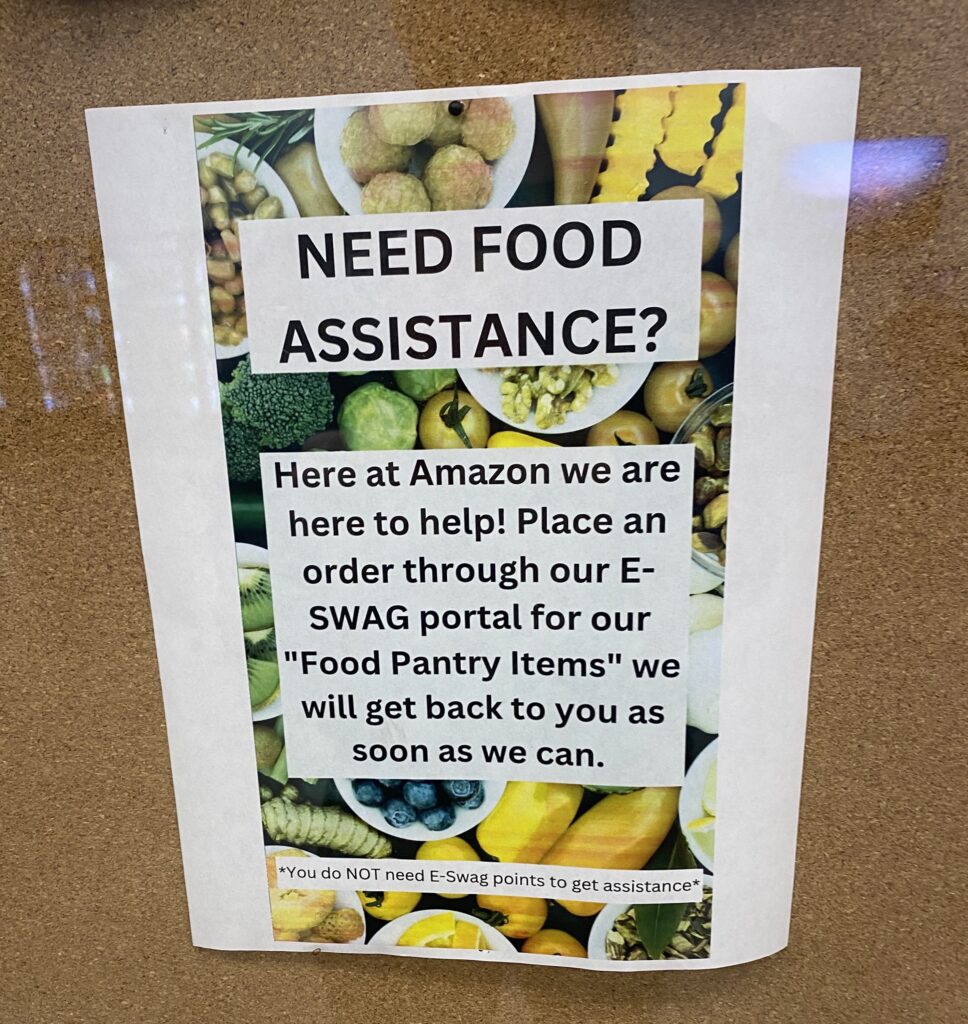

Our break room has a discrete sign: “Need Food Assistance?” You can pick up canned goods at the HR-maintained food pantry, Amazon effectively admitting it does not pay enough to eat.

The company holds little raffles, donut breaks, and T-shirt giveaways that do not fool anyone.

“Just trying to make us forget how bad they’re treating us,” says one of my co-workers.

That anyone could still describe Amazon as a “pretty nice job” testifies to what a pittance corporations get away with paying working people. You earn even less than our US$15.50 an hour flipping burgers at McDonald’s or cashiering at Walmart.

The starvation wages paid by corporate America remain a dismal open secret.

HOW TO MAKE IT BETTER

Unionizing efforts at Amazon have attracted much attention. But they have been unsuccessful so far, except for a solitary Staten Island warehouse, JFK8. There, the union has been bogged down by its own infighting and Amazon’s legal challenges to its certification. It has not yet been able to negotiate a better contract.

A worker-led group called Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity & Empowerment (C.A.U.S.E.) has been trying to organize the RDU1 Fulfillment Center. The overwhelming majority of workers our research team has spoken with support the unionization campaign, at least in principle. But in practice, unionization is a hard feat compounded by high worker turnover, fears over job loss, and the exhaustion workers suffer scrambling just to get by.

“We know it’s a marathon not a sprint,” says a worker-activist at the Raleigh facility.

From its origins in Bezos’ Seattle garage, Amazon has prided itself on innovation. Paying a living wage gives the company another chance to lead.

Despite some recent cutbacks, Amazon has the money. CEO Andy Jassy took home a whopping US$212.7 million in compensation in 2021. That’s some 6,474 times more than the median wage of the hundreds of thousands of Amazon employees who sweat the hours away in facilities like mine.

Studies show that Amazon’s pay rate becomes a benchmark for other businesses. Should the company choose to raise pay dramatically, others might be forced or shamed into following. Raising pay would at minimum create immense goodwill for the company.

“The World’s Best Employer,” as Amazon’s happy-speak now has it?

Not so long as Amazon Associates have to grab a can of SpaghettiOs from the HR food pantry to feed their kids dinner.