Through Film, Discovering Hope in the Face of Environmental Destruction

FILMMAKING IN THE ANTHROPOCENE

A group of 12-year-olds enters a decrepit building outside an oil refinery. The smokestacks send up menacing orange flares, and the heavy air smells of sulfur. The children set up their camera and zoom in on a man holding up a complicated-looking gadget that resembles a giant walkie-talkie. Desmond D’Sa, the head of the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance in South Africa, explains that it’s an air quality measurement device: a key tool for local activists working to document the harmful toxic gases the children inhale daily.

The resulting film, Pollution Kills, shows how young people grapple with life in the township of Wentworth in South Durban, one of the most industrially polluted places in South Africa. Home to the largest port in Africa and hundreds of chemical plants, the area produces roughly a tenth of South Africa’s GDP. Shaped by the brutal history of racist apartheid-era zoning policies, South Durban is simultaneously an economic powerhouse and a furnace that scorches its residents through sky-high rates of cancer and respiratory illnesses.

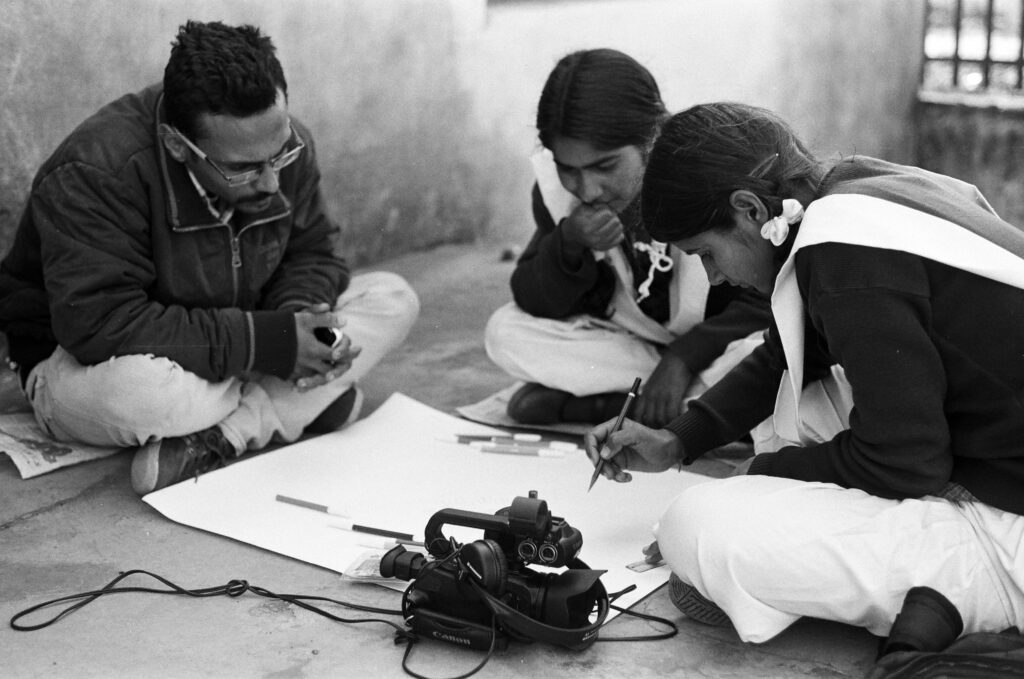

The children interviewed D’Sa during a series of video workshops I facilitated in local primary schools. In these workshops, children learned to use cameras and make short observational films about their daily lives. They then shared their work with others in the community and talked about the intended meaning of the films in their own words. These workshops were part of the research behind Educating for the Anthropocene, my new book about learning for the future in the face of unprecedented environmental destruction.

A month later, when the students showed their films to their peers, a weight seemed to lift. Audience members smiled and nodded along to the depictions of activists like D’Sa who are working to hold the government accountable in enforcing the local community’s constitutionally guaranteed right to a clean environment.

As part of my exploration into what effective education might mean in the Anthropocene, I also facilitated video workshops with young people in Pashulok, India. The Indian state forcibly moved thousands of people displaced by the construction of the Tehri dam in the northern state of Uttarakhand to Pashulok in the early 2000s, despite decades of protests from activists and local people against the dam. Like those in South Durban, the students I worked with in India also chose to focus on documenting the work of activists fighting for environmental justice in their communities.

Although South Durban and Pashulok are on different continents, were shaped by different histories, and face different environmental threats, the films the students made share remarkable similarities. In both places, I saw how the students’ perspectives shifted as they delved deeper into filming life in their communities. Most of them started out understandably anxious about their futures. But through the process of interviewing community members and hearing their stories, the children began to express a sense of hope that a different future is possible—through activism.

It’s a lesson for us all: Given the acute despair that many people feel in the face of global environmental destruction, finding hope even in small doses is more necessary than ever.

REIMAGINING THE FUTURE

I started the workshops by asking students to draw pictures of what they imagined their community might look like 100 years from today.

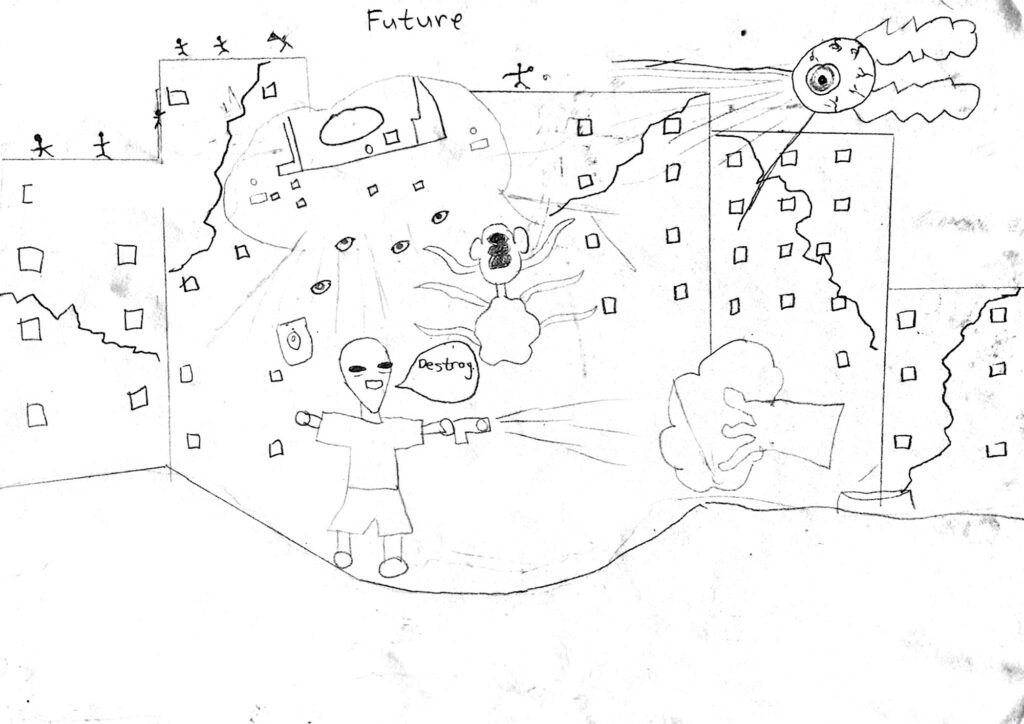

The lone word “destroy” in this drawing by a 12-year-old South African student captures the dystopian spirit that many young people expressed toward the future. The pictures rarely showed signs of nonhuman life and often contained traces of violence both against the environment and between people.

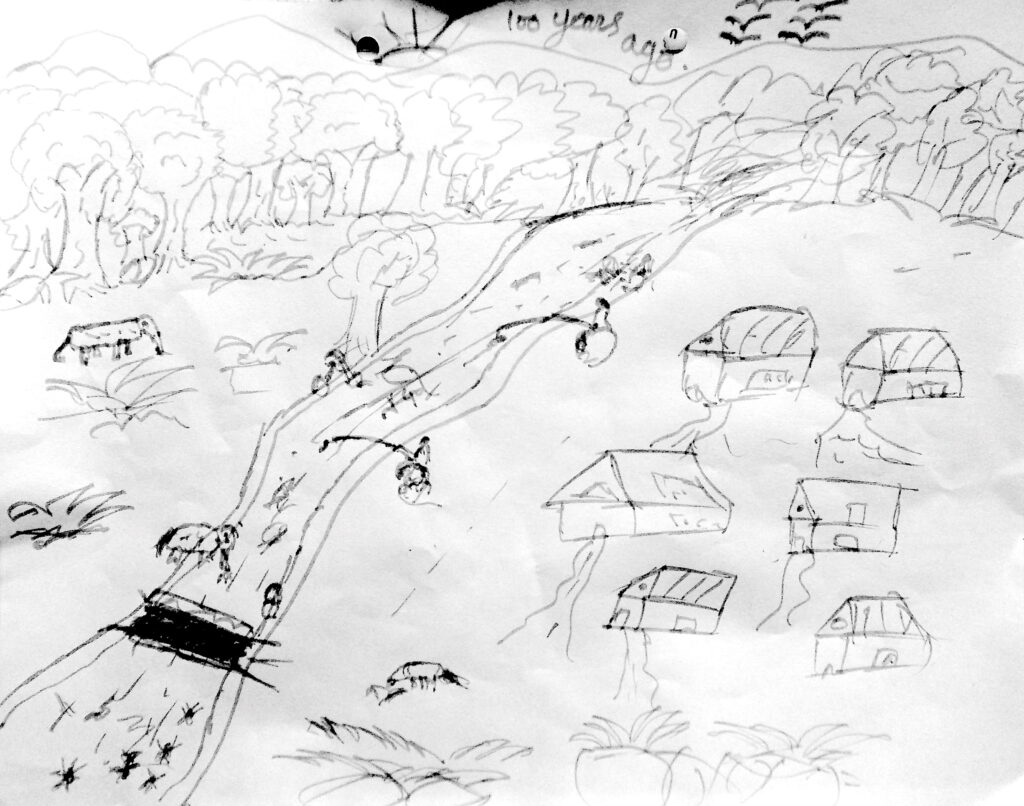

In contrast, when I asked students to draw what they imagined their communities looked like 100 years ago, they tended to depict more peaceful settings of human beings and their natural surroundings.

In this drawing by a student from India, people are fishing and swimming in the river rather than damming it.

When taken together, the drawings of the past and the future suggested the young people in both South Durban and Pashulok tended to fear the future and long for a return to the past. But through the filmmaking workshops, I saw how their imaginations and understandings evolved over time.

We would begin by mastering the technical skill of filmmaking, and the students would then take the cameras home and keep them for several weeks to create films.

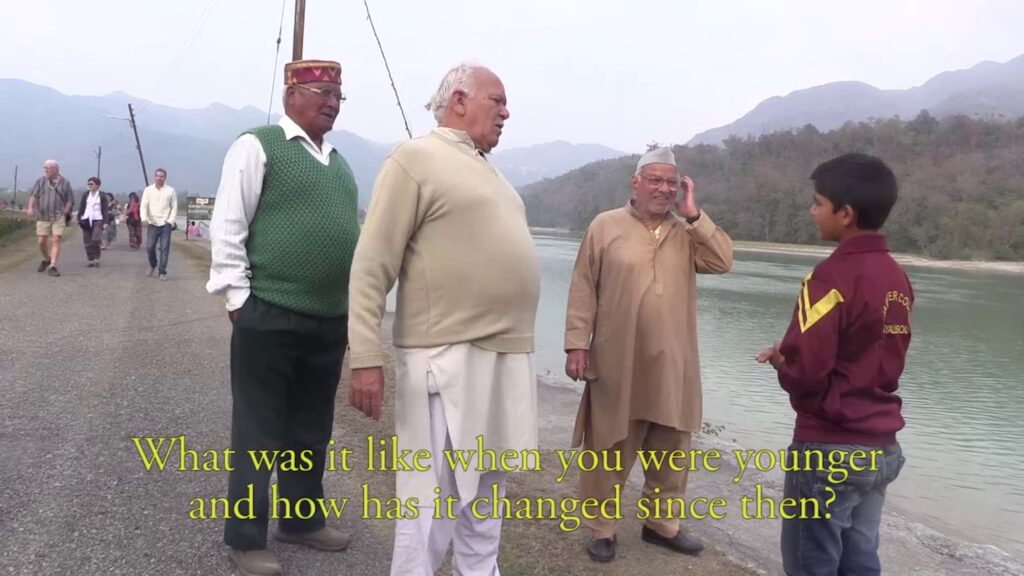

In India, the students made a film called Ganga the Life Giver. In it, they document how people in the surrounding regions relate to the Ganges (Ganga) River. The student filmmakers included older people from the community—many of whom were anti-dam activists—and talked to them about how the environment has changed in this part of India over the decades. Some of the elders shared stories of what life was like before the damming of the river.

“We could talk to our peers all the time, but the film gave us a chance to speak to the elders in our community,” one student told me.

In South Africa, the young filmmakers also gravitated toward activist figures in their community. In Pollution Kills, D’sa shows them an air quality measurement device and explains how his organization fights to protect the health of people in the community. The students chose to make this a central scene in their film, highlighting not just the plight of the local community but also the spirit of fighting back.

In another film from South Africa, Wentworth Changing to Progress, students focused on the many change-makers in their community. In one of the scenes, they showcased Dance Movement, a weekly dance class for young people in the area. Filmed along Treasure Beach, a picturesque coastal area just over the hill from the South Durban Industrial Basin, this scene contrasts starkly with the smokestacks and poverty seen in Pollution Kills.

Such storytelling moments made it clear that hope can be found—and learned—even in the face of unspeakable environmental destruction.

DISCOVERING HOPE

To me, Pashulok and South Durban feel like spaces of the future. Communities in these cities experience levels of environmental ruination—and associated human suffering—that much of the rest of the world has yet to face. And yet, young people living in these places are finding hope in grassroots environmental activism. They taught me that we don’t need to look very far for hope; if we look hard enough, we can often find it within our own communities.

I realized that young people were drawn to activists not only as beacons of hope, but as guides in imagining a different future. Community-based art and filmmaking helps young people recognize they are political beings with a voice that matters, rather than passive absorbers of knowledge or implementers of someone else’s blueprints for what’s possible.

Telling stories and dialoguing with other members of their community engage young people’s capacities for radical imagination—the ability to think outside the box. These also allow them to grapple with their emotions about environmental decay and destruction—fear, anxiety, anger, despair—and to channel them into action.