Inside Amazon’s Union-Busting Tactics

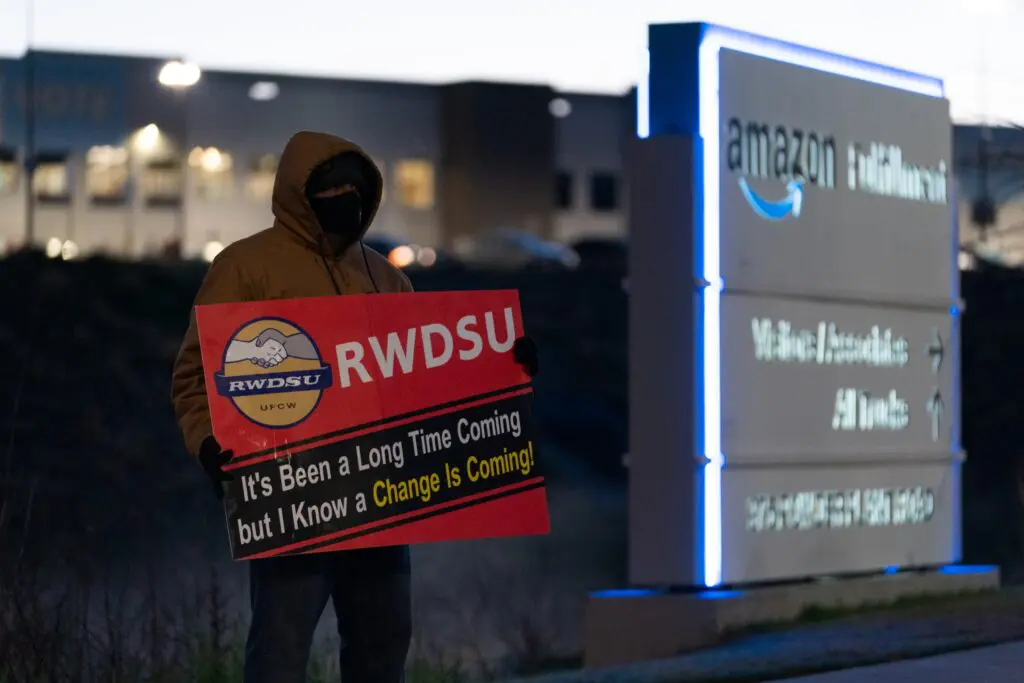

In the notoriously anti-union U.S. South, a Volkswagen plant unionized. After months of striking, unionized Hollywood writers won better pay and protections. These headline-grabbing wins belong to lists of 4,187 union elections and 809 organized strikes over the past two years.

With about 70 percent approval, unions enjoy near-record high public support among those surveyed in the U.S. It seems a new era of labor activism is underway.

But a deeper dive into the data muddies this picture. In 2023, only 6 percent of private sector workers in the U.S.—about 7 million out of 123 million—belonged to a union. Companies such as Amazon, Walmart, and McDonald’s continue to pay starvation wages, fire at will, and treat workers as poorly as they please.

From the outside, the labor movement’s troubles gaining traction might seem puzzling. Don’t workers know that unions almost always better their conditions?

I’m an Amazon worker myself but also a professor of anthropology at Duke University. I teach a class about technology, surveillance, and the workplace with a focus on Amazon’s rise into a global megacorporation. But, as we anthropologists do, I wanted to learn more firsthand. A couple of years ago, I got an Amazon warehouse job to do undercover fieldwork.

In the warehouse, I’ve witnessed the tactics Amazon and other corporate leviathans use to fence unions out. They spend big money to coax, prod, and frighten workers away from organizing. Labor activists have the deck stacked against them despite wishful sloganeering about a mass movement.

But still, it’s worth the fight for the benefits unions bring.

Getting an Amazon job was easy. I completed an online authorization for a background check—and took a drug test. No resumé. No interview. The company apparently even hires anthropology professors if they can do the job. Nobody cared when I’d pull out my notebook to scribble field notes, hardly undercover at all.

After a stint at a smaller Amazon facility, in 2023, I moved to a cavernous cement Moria of a warehouse called RDU1 near Raleigh, North Carolina. More than 5,000 of us labor there, day and night, to get out those blenders, diapers, dog toys, cock rings, and Bibles.

I started out packing. Packers must box more than two orders a minute at a cramped workstation, minds going numb from the conveyor belt din. Fail to make rate? A couple of warnings, then you’re fired.

“Santa’s Sweatshop,” we call the pack line during the frenetic holiday shopping season. Amazon makes 11-and-a-half-hour shifts mandatory from Black Friday to Christmas Eve.

I eventually transferred to the loading dock, although it was not much better. What’s called “water-spidering” entails plastic-wrapping pallets of boxes and then loading them onto big blue semis. I’d trudge more than 20 miles a day closing shipments as the algorithmic surveillance system tracked my movements.

The pay at RDU1? An “Associate”—as Amazon euphemizes us warehouse drones—starts at US$16.50 an hour, capped at US$19.20. That’s not half the US$41.54 that economists estimate as the minimum living wage for an adult with a child in the Raleigh area.

I have RDU1 friends who sleep in their cars because they can’t afford rent.

Historian Nelson Lichtenstein wrote in 2013 that the U.S. labor movement had bottomed into “unprecedented weakness.” Trade union membership had been trending downward for decades between company scare tactics, weak labor laws, and their own stale bureaucratization.

But the mood has changed in the last few years. Existing unions, such as the United Auto Workers (UAW) and Writers Guild of America (WGA), organized strikes that led to big victories in contract negotiations. Baristas formed Starbucks Workers United with more than 470 affiliates nationwide. Labor organizing has been reenergized.

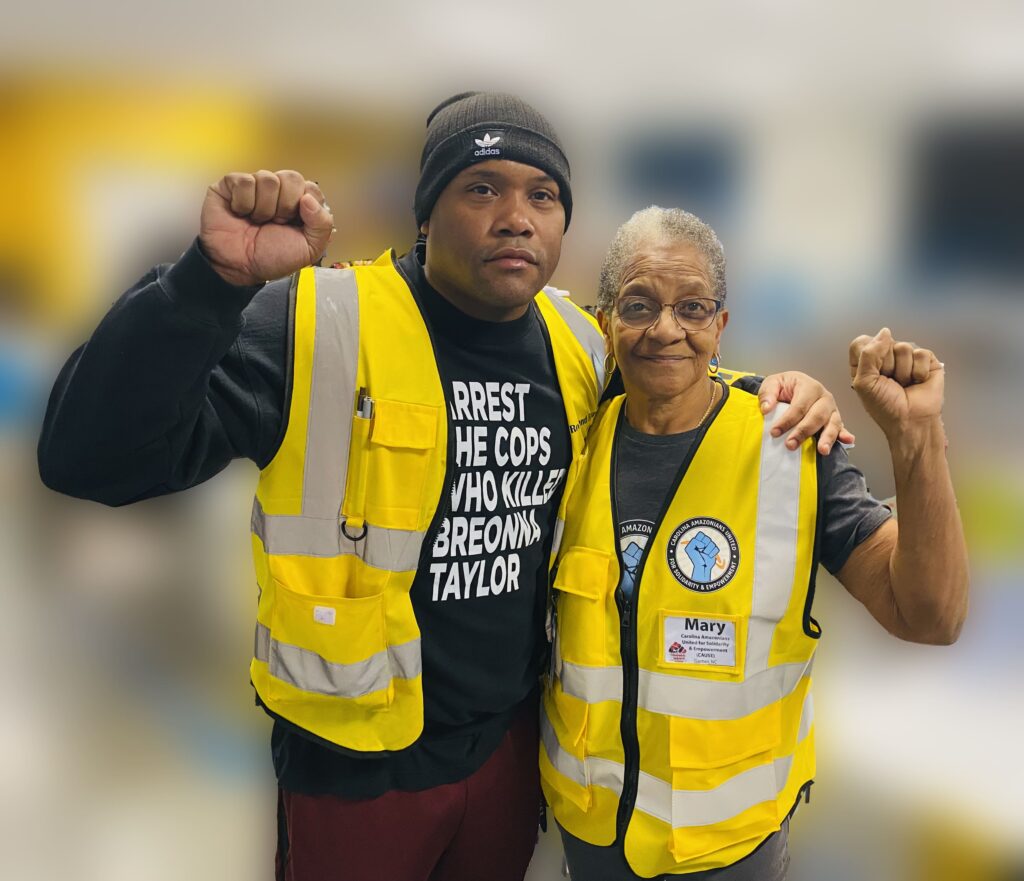

To try to unionize RDU1, a group called Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity and Empowerment (CAUSE) formed during the pandemic. The effort has been led by a magnetic former pastor, Ryan Brown, and a charming streetwise matriarch, Mary Hill, or Ma Mary as everyone calls her.

Ma Mary is 70, grew up in Jim Crow Louisiana, and packs full time despite two surgeries and now chemotherapy for colon cancer. (She’s relying on a GoFundMe to cover her thousands of dollars in co-pays.)

“You got to organize,” she says, “If it wasn’t for MLK and Rosa Parks, I’d still be f-ing picking cotton.”

As a researcher working in the warehouse, I hadn’t planned on being part of a unionizing effort. But the dreadful conditions at RDU1 compelled me to join CAUSE. I became the union’s lead organizer on the loading dock, handing out CAUSE T-shirts and chatting up fellow workers about organizing.

The need for unions has never been greater. There are plenty of jobs in the U.S. today but not the good-paying unionized factory variety of General Motors or U.S. Steel. Instead, more than 60 million workers—almost half the U.S. workforce—flip burgers, restock aisles, and pack boxes at poverty wages in the post-industrial economy. It’s commonplace for employees of Walmart, Amazon, or Target to line up at food banks just to feed their kids.

These companies can certainly afford to treat their workers better. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos—he of the superyacht, mansions, and hobby rockets—weighs in at over US$180 billion in net worth. His company is valued at more than US$2 trillion.

Although unions don’t fix everything, they help. In terms of median usual weekly earnings, unionized workers earn over 15 percent more than their nonunionized counterparts, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. When workers vote for union representation, companies lose the almost unchecked power over the workplace that prompts political theorist Elizabeth Anderson to call them “private governments.” Companies become legally obligated to bargain over wages, benefits, and shop floor conditions.

Countries like Sweden, Denmark, and Taiwan with strong unionization rates show greater worker satisfaction, higher productivity, and better workplace conditions—with companies still raking in big profits.

But unionization isn’t a fair fight. Amazon has spent more than US$17 million on outside “union avoidance” consultants in just the last two years. The company’s Employee Relations department also trains its own army of homegrown union busters.

What about CAUSE? We mom-and-pop it: a GoFundMe campaign, selling some T-shirts, not much more. Big unions like the UAW and the National Education Association have war chests, but CAUSE is a grassroots worker-led organization. We have so far resisted overtures to join the Teamsters, fearing for our independence.

Big companies have also refined a playbook of anti-union techniques that sociologist Donald Roy called the “sweet stuff, fear stuff, evil stuff.”

The sweet stuff: balloon arches, a raffle for earbuds, thank you videos from the CEO, and—yes—literal candy, which managers wheel around in bowls during the grueling peak season. (Stale, I’m afraid, true to the Amazon’s core principle of “frugality.”)

Like many companies, Amazon employs cognitive psychologists, or “mood technicians.” They come up with infantilizing gimmicks like Wacky Tacky T-shirt Day, trying to placate workers without any real change.

“They just trying to make us forget how bad they treating us,” says one of my warehouse friends, Jontavis (a pseudonym).

As to the fear stuff, I’ve learned the hard way. Amazon fired me earlier this year. The reason they cited? A parking lot toast of rum I made to CAUSE after a soul-sucking holiday shift—and posting a selfie of it captioned with a snarky comment about Bezos.

The real reason? Union organizing.

Because the law bans firing anyone for union organizing, Amazon looks for excuses: a low work rate, a safety violation, a sip of rum.

I had ignored one of Ma Mary’s prime organizing directives: CYA. Cover Yo Ass.

“Why do smart people do the stupidest shit?” she asked me.

Company policy bans drinking only during work hours, but my ill-advised toast gifted Amazon an easy-bake pretext for getting rid of me.

I’ve appealed to the government agency tasked with safeguarding worker rights, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). But the damage is done. Reverend Ryan, Ma Mary, and I were the only three open organizers on the floor. Now I’m gone.

Stories about firings like mine seed warehouse fears about union involvement.

And there’s the evil stuff: As CAUSE has gained strength, workers have been summoned to mandatory “captive audience” meetings. Here union busters from Employee Relations talk up Amazon’s virtues and spread flat-out evil lies about the union. At one gathering a few weeks ago, a man-bunned Gen Zer in a yellow work vest falsely claimed our homegrown worker-led effort was an “external” group that might share confidential worker data with unspecified bad actors.

Zooming out to the national level, Amazon recently filed a legal brief and joined Trader Joe’s and SpaceX in arguing that the NLRB is unconstitutional. By trying to abolish the NLRB, these corporate giants malevolently seek to sever the one frayed lifeline of recourse for wronged workers.

If company union-busting efforts weren’t bad enough, the structure of the 21st-century economy further complicates making common cause.

The lousiness of so many jobs leads to wickedly high turnover, or what economists call “the churn.” More than half of new RDU1 hires flee within a few months, hardly long enough to become CAUSE supporters.

The heterogeneity of the modern workplace impedes labor organizing too.

Although RDU1 has a plantation-like feel with a majority Black workforce and predominantly White managers, we’re a diverse collection of souls: queer, teenage Latinas and tractor cap Trump supporters; anime nerds and Army vets; Muslims and Christians; metalheads; and migrants from around the world.

Spreading the union gospel to this varied crowd can be tough. Even striking up a conversation is a challenge. It’s loud and chaotic, and we’re trying to get our jobs done with just two half-hour breaks in the standard 10-hour day.

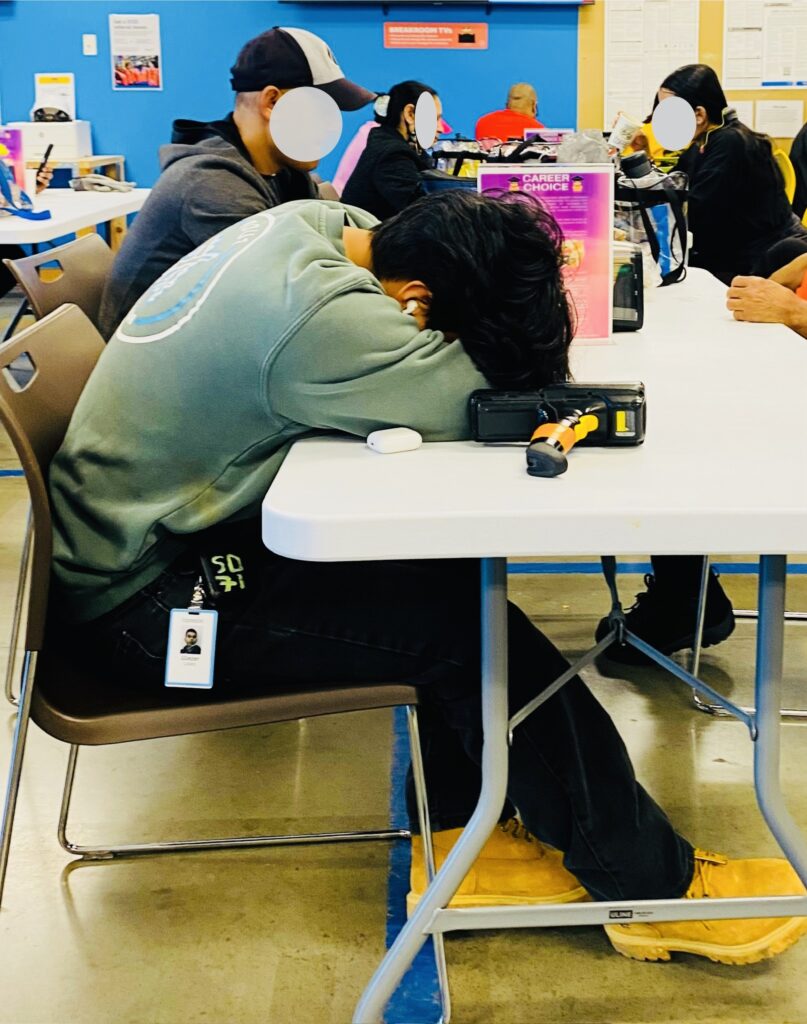

Everyone is bone-weary from the work grind and family obligations, with little energy left for union meetings. Sheer exhaustion—“the dull compulsion of economic relations” as Karl Marx put it—may be the single biggest barrier to workers rising up.

“It’s David versus Goliath,” says Ryan Brown, the pastor-turned-CAUSE leader.

Just how bad workers have it at RDU1 and millions of other jobs means unionizing efforts will continue no matter the odds against success.

We’ll continue to fight through moments of doubt and discouragement. Because now and then, a stone can bring the giant down.

Editors’ note: If you would like to support CAUSE, you can donate to their GoFundMe solidarity fund.