In a Genocide, Who Are the Morally Upright?

On April 21, 1994, Felicite Niyitegeka took in a sight many Rwandans had come to dread: a line of minibuses pulling up to her door. For much of the month, members of the Interahamwe militia—agents of the majority Hutu-led government—had been rounding up members of the Tutsi minority, taking them to killing fields where they were shot or hacked to death with machetes.

Though the Hutu and Tutsi peoples shared a long history and a cultural heritage, animosity had festered between them for many years. In the early part of the 20th century, Belgian colonizers decided Tutsis were more European looking and rewarded them with positions of power, angering the Hutu. But in the late 20th century, Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, became president and his administration discriminated against Tutsis; he installed mostly Hutus in his dictatorial regime. On April 6, 1994, a missile attack shot down Habyarimana’s plane. After the fatal crash, Hutu extremists assumed power, claimed Tutsis had killed the president, and embarked on a vengeful campaign of mass slaughter.

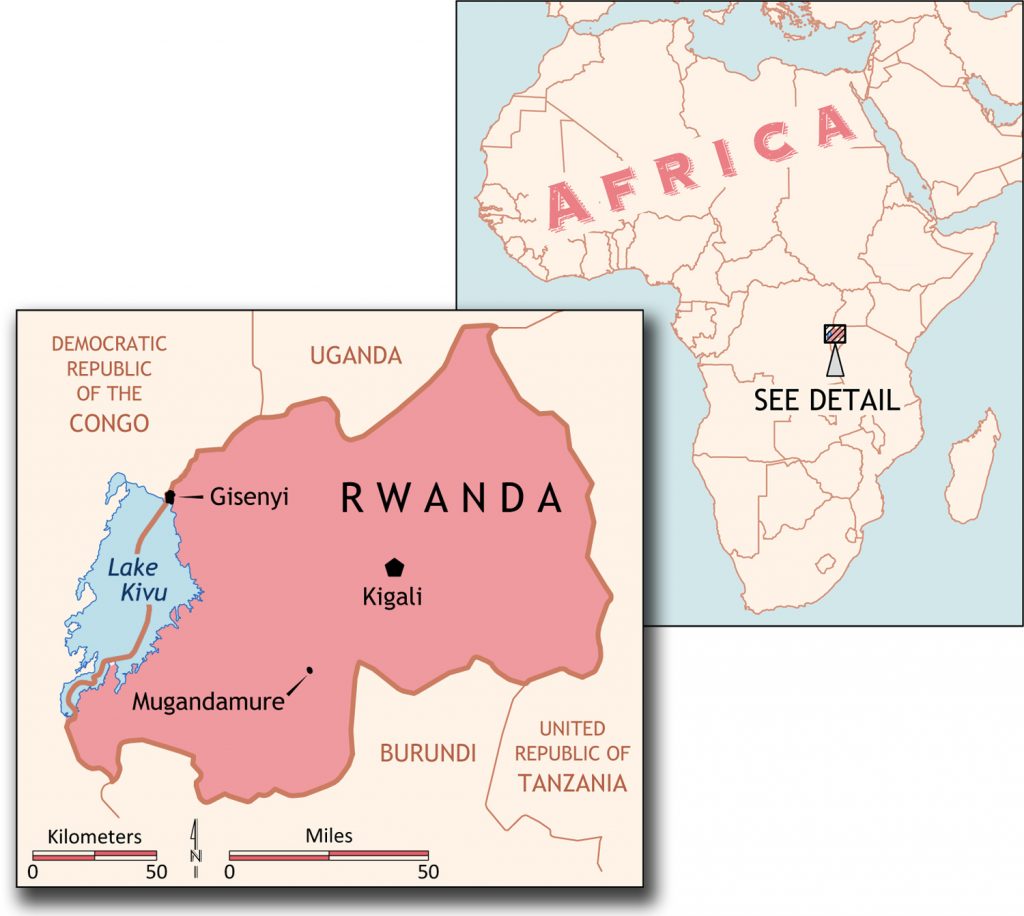

In the midst of the chaos, Niyitegeka, a dedicated lay worker in the Roman Catholic Church, was saving as many Tutsis as she could. She helped them across the Congolese border and hid them in the compound where she worked, the Centre Saint Pierre in the city of Gisenyi. But the Interahamwe had learned of Niyitegeka’s rescue efforts and hatched a plan to capture all of her charges.

After the militiamen forced their way into the compound, they told Niyitegeka that they intended to spare her life since she was a member of the favored Hutu majority. The dozens of Tutsis living at the compound would have to board the buses to their deaths.

The killers had offered Niyitegeka an out, but she refused to take it, with full knowledge that she could be killed as well. She told the soldiers that, whether in life or in death, she would remain with the Tutsis she had sheltered. Singing and chanting, she followed them onto the buses, which headed for the notorious Commune Rouge, a public cemetery that served as a killing field. There, alongside her Tutsi friends, Niyitegeka was slain by an assassin’s bullet.

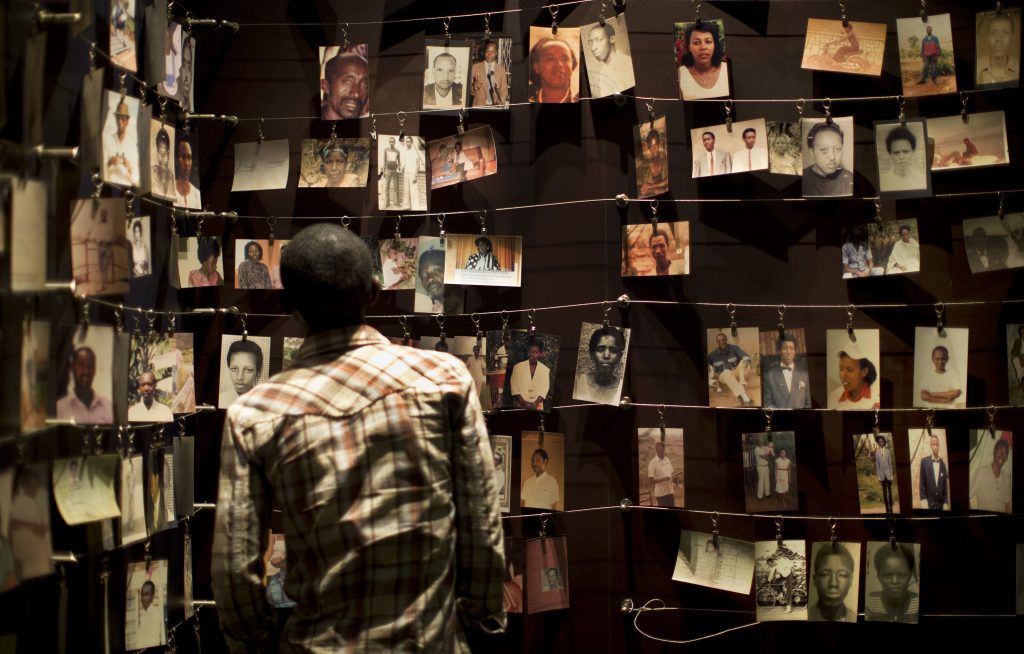

What motivated rescuers like Niyitegeka to put their lives on the line to save others during the 100-day genocide? And why had so many others remained on the sidelines or even participated in the killing? Questions like these haunted Jennie Burnet for years. As an anthropology graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she’d interviewed a variety of Rwandans after the 1994 genocide, in which about 800,000 Tutsis had been slaughtered. From time to time, people Burnet met would talk about how they—or someone they knew—had protected Tutsis during the height of the killing. These Rwandan rescuers, Burnet learned, had pulled off feats that were as bold and brave as those of Holocaust rescuers. They had hidden Tutsis in their homes and stables, smuggled them across the border to safety, and warned them of planned killings so they would have a chance to escape.

Listening to these accounts, Burnet began to wonder just how common rescue behavior actually was during the genocide. What had compelled some people to push past their own fears to help those whose lives were in danger? She thought about studying rescuers’ stories and motivations in more detail, but she was initially wary. When she broached the topic of genocide with Rwandans she met, few seemed to want to talk about it, and most of her colleagues didn’t seem very enthusiastic about it either. “I kept trying to convince people with the necessary background to take on the project, because I didn’t feel I had the skills,” says Burnet, now an associate professor of global studies and anthropology at Georgia State University in Atlanta. “I never found someone who had the interest or the time to take it on.”

But in the following years, Burnet felt increasingly ready to take up her own suggestion. As she gained experience and took intensive courses in Kinyarwanda, Rwanda’s national language, her confidence in doing fieldwork grew. And by 2012, many Rwandan genocide perpetrators had been tried and convicted in gacaca (community) courts, which brought a certain degree of closure to the national nightmare. Gradually, some Rwandans became more open to reflecting on what they had seen and done during those fateful months of 1994.

With the help of a National Science Foundation grant, Burnet took several research trips to Rwanda in 2013 and 2014 to interview more than 200 people, including rescuers, witnesses, and genocide perpetrators. The stories she has uncovered reveal surprising ways human selflessness can surface even as ethical norms are slashed to bits and entire communities disappear off the face of the earth.

“It depends on people’s hearts. We are created differently.”

Rescuers weren’t always as morally righteous as many people might assume, Burnet has found, and the success of their efforts often hinged on accidents of geography and timing. Beyond circumstance, though, what motivated rescuers to act was a burning inner conviction that what happened to their fellow human beings mattered. “One can have pity, take the risk, and save people. Others say, ‘I cannot involve myself in these troubles,’ because they are afraid to take the risk,” one genocide survivor told Burnet. “It depends on people’s hearts. We are created differently.”

From an early age, Burnet had been curious about what drives people to risk their own lives to save others. She had read Anne Frank’s diary as a child, impressed at the bravery of the Dutch rescuers who helped the Frank family while they were hiding from the Nazis. As an undergraduate at Boston University, Burnet took a course with Elie Wiesel, the Auschwitz and Buchenwald survivor whose memoir Night is a classic of Holocaust literature. Wiesel “designed his courses intentionally as an experience,” Burnet says. “He talked a lot about evil and goodness, and that shaped a lot of my thinking.”

That moral influence helped ground Burnet as she ventured into eight different regions of Rwanda to interview rescuers, perpetrators, and observers by the dozens. She and her research partner, anthropologist Hager El Hadidi, stayed in rustic guesthouses and drove over bumpy dirt roads to the communities they had chosen, keeping up a grueling research pace.

As she traveled from region to region collecting people’s testimonies, Burnet knew that the Rwandan government could decide to stop her at any time. In today’s Rwandan political climate, conducting research like this is an act of bravery in itself, says Lee Ann Fujii, a University of Toronto political scientist and author of Killing Neighbors: Webs of Violence in Rwanda. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) regime now in power is invested in the myth that almost all Hutus participated in the genocide, as opposed to a fraction of Hutus loyal to the extremists that took power after Habyarimana’s death. Many rescue stories are considered an affront because they contradict this official narrative, and the regime has blacklisted some scholars who publish work critical of the government.

After completing her interviews in 2013 and 2014, Burnet began combing the interviews she’d gathered for dominant themes that shed light on rescuers’ selfless acts. One of the first things she noticed was that lifesaving rescue efforts were common. Dozens of people she interviewed had taken part in a variety of rescue operations during the genocide, from supplying people in hiding with food and clothing to paying militiamen to release Tutsis marked for death. “Rescuer behavior was widespread,” Burnet says. “Many Rwandans engaged in rescuer behavior for long periods of time, sometimes weeks, until it was no longer possible.”

When Burnet asked rescuers why they had done what they did, they overwhelmingly said they viewed their fellow Rwandans—whether Hutu or Tutsi—as worthy human beings like themselves. That core belief motivated them to save others who were in danger, even though it meant putting their own lives at risk. “They almost all said that it’s what any decent human being would do,” Burnet says. “It has to do with identifying as a certain kind of person.” University of California, Irvine, political scientist Kristen Renwick Monroe came to a similar conclusion after interviewing Holocaust rescuers, reporting that they “saw themselves as individuals strongly linked to others through a shared humanity.”

Reflecting on why some Rwandans, but not others, tried to help Tutsis, one rescuer told Burnet, “The one who had a beastly heart didn’t save the person, but the one who had a merciful heart, which understood that a human being is a human being, saved that person. That’s how we saved people.” Another rescuer added, “The first reason why some people saved others is because they understood that every person is like themselves—and that, if he was being hunted today it’s maybe because you could also be hunted the following day, that if he dies today, you can die tomorrow. … We understood that no one has [the] right over another person’s life.”

A profound sense of shared humanity also motivated Felicite Niyitegeka, who was well aware of the dangerous territory she’d entered when she decided to become a rescuer. But her dedication to her fellow Rwandans’ safety and survival overrode her doubts. When Niyitegeka’s brother advised her to flee and avoid the killing squads, Niyitegeka wrote back:

Thank you for wanting to help me. I would rather die than abandon the 43 persons for whom I am responsible. … If God saves us, as we hope, we shall see each other tomorrow.

Though neither Niyitegeka nor those she sheltered survived the genocide, several people Burnet interviewed in Gisenyi shared Niyitegeka’s story and testified to her compassion and heroism. Her story echoes that of Janusz Korczak, a Warsaw Ghetto orphanage director who willingly accompanied his charges on a 1942 transport to the Treblinka death camp in Poland, where all of them died.

Some rescuers not only lived out the principle of caring for everyone around them but also attempted to foster it in others. One priest Burnet interviewed ran an orphanage in southern Rwanda that housed many children from displaced families. Some of the children were Hutus who harbored negative feelings toward Tutsi children who lived under the same roof. Recognizing the importance of promoting unity during such a dangerous time, the priest spent a lot of time talking to the children about the importance of supporting others, even those who belonged to a different group than they did. In the end, the children sheltered at the orphanage survived.

Many rescuers also stated that their religious ideals had prompted them to act. They pointed, for instance, to verses from the Quran stating that murder is a sin and that all humans share the same blood. Their testimony and actions supply a unique rebuke to those who claim Islam is a religion of violence that promotes hateful behavior. Inspired by their faith’s moral tenets, Muslims in the city of Mugandamure and elsewhere protected Tutsis they had smuggled into their homes, building roadblocks out of whatever they could find to keep the killers from entering. “Our religion, Islam, doesn’t allow people to spill our neighbors’ blood,” one rescuer explained to Burnet. “We looked and we only saw brothers here. You could not think about killing this person, because he was a brother, someone who would have rescued you too, if you needed help.”

Some of these rescue efforts, Burnet says, were also rooted in certain religious communities’ longstanding sense of themselves as separate from other Rwandans. Under Belgian colonial rule, Muslims had to live in designated areas called “Swahili camps” that were much like ghettos, and this kind of persecution may have sensitized them to the plight of Tutsis whose identities also put them in danger. Psychologist Ervin Staub of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, has found that when people have been through deeply traumatic life events themselves, they’re more likely to commit to helping others in trouble. This response, which Staub calls “altruism born of suffering,” may have helped spur some Rwandan rescuers’ heroic acts.

But while many rescuers valued morality and empathy to an unusual degree, those values were not sufficient by themselves. Situational factors like location and geography could also help or hinder rescue missions. In Gisenyi, a city not far from the Congo, rescuers were able to save many Tutsis because the border was in the vicinity and only partially fenced. Burnet interviewed import-export traders from the area who had engaged in rescue efforts. Many of them had taken part in illegal smuggling and were experts at guiding Tutsis through fence openings undetected, when there were no guards in sight. “They knew how to get things across the border secretly,” Burnet says. “It gave them great opportunity.”

Similarly, local fishermen or others near Lake Kivu were sometimes able to ferry escaping Tutsis across the lake to the Congolese border. One such rescuer had saved many Tutsis, hiding them in banana groves around his house or at a nearby coffee plantation before paddling them in his canoe to safety. When Burnet asked him why he’d rescued so many people, he answered, “I’m so poor in this life, how is it possible to lose both heaven and earth in this lifetime?” In areas further from the border, however, few viable escape routes existed, making rescue operations all the more difficult.

Not only were successful rescues highly dependent on the whims of circumstance, but unyielding outside pressures could also eat away at rescuers’ moral resolve. While most rescuers were deeply concerned with the fate of those around them, they were also vulnerable to the trickery, threats, and demands of the Interahamwe. As the genocide gathered momentum, Interahamwe militiamen stormed homes in targeted areas repeatedly, looking for fleeing Tutsis. During these searches, household heads knew the militiamen might kill them, too, if hiding Tutsis were found on their property.

The constant fear of death, of yet another group of militiamen storming into their homes, taxed the endurance of even the most compassionate rescuers. Many Rwandans initially helped threatened Tutsis, but some lost the will to continue their rescue efforts as the killing operations dragged on. Those who committed genocide looted and demolished property, terrorized dissenters, and raped Tutsi and Hutu women. As people faced all this chaos, quite a few opted to focus on their own survival and that of their families. “It was pretty normative in the early days of the genocide that people’s reaction was to help their friends and neighbors,” Burnet says. “That changed as the genocide evolved and continued.”

One Hutu rescuer told Burnet about his efforts to save a Tutsi acquaintance. He had hidden the man in his home for nearly a month, feeding and sheltering him as he evaded the onslaught of the Interahamwe. But when the rescuer and his family decided to flee the war-torn area, they decided—with regret—that they had to leave the man they’d been protecting behind. “We could not bring him with us. I don’t know what happened to him,” he said. “I do not talk about these things because people can misunderstand or twist my words to say that I am the one who had him killed.”

As the bodies piled up, the Interahamwe also put more pressure on ordinary Rwandans to get involved in the killings. Militia groups rounded men up on the pretext that they would be carrying out a routine night-security patrol. When the men appeared for service, militia heads told them to track down Tutsis who were attempting to hide or flee from their killers. “People went to the security patrols as a way to look like they were complying with the government,” Burnet says. “They didn’t intend to participate in the genocide.” Still, after their surprise initiation, some of these complicit men became more directly involved in the killing process, especially when they felt that disobeying the militia’s orders could put them or their families in danger. “It’s the slippery-slope phenomenon,” Burnet says. “You start out doing something that’s a little bit wrong, but that makes it easier to do something that’s more wrong.”

Read more from the archives: “The Green Woods of Resilience.”

Rescuers were by no means immune to such slippery-slope thinking. A number of people Burnet interviewed helped rescue Tutsis and rounded up or killed people themselves—often because they felt their own lives could be at risk if they did not do as the Interahamwe demanded. “Not only did a person have to have the will to help someone,” Burnet says, “they also had to make the decision many times a day to not become implicated in the genocide. There was a combination of explicit and implicit threats people felt they were under.” Her findings shatter the common assumption that rescuers are morally above reproach. They may have a deep respect for their fellow human beings and a burning desire to help them, but like anyone else, when a situation turns deadly they can make decisions they later regret.

If even the best-intentioned rescuers sometimes fall short of their moral ideals, how realistic is it to encourage rescue behavior when persecution and killings begin? One constructive way to assist rescuers, Burnet says, is to stave off or alleviate the pressures they face before those pressures become intolerable. “Early intervention is key,” she says. She argues that if the United Nations had not reduced its peacekeeping force during the genocide, rescuers would not have had to hold out in dire conditions for as long, braving ongoing raids and the threat of death in order to save their fellow citizens. As a result, many more Tutsis would be alive today. “It’s about the space for rescuing,” says Fujii, the political scientist. “Outside powers can enlarge those spaces.”

Elevating the significance of rescue behavior can also help promote it in others. The rescuer heroes in Burnet’s narratives can motivate people to help fellow human beings in desperate circumstances, says University of Kentucky anthropologist Monica Udvardy. As sociologist Samuel Oliner’s rescue research has shown, selfless role models can be crucial in shaping our future capacity to help others. “There’s definitely a role model effect,” Udvardy says. “One has to act, one has to be involved, rather than just shaking one’s head and saying, ‘That’s too bad.’”

In Rwanda, where social norms encourage people to blend in, acknowledging rescuers and sharing their stories can be a complex undertaking. Through her immersion in Rwandan culture, Burnet came to understand that most rescuers did not want public recognition for their lifesaving deeds—and that, in fact, many preferred to remain anonymous. “Rwanda is a place where conformity is a form of protection. You hide by being like everyone else,” Burnet says. “There is a strong desire not to be exceptional.” And while many Tutsis are grateful for Hutu rescuers’ efforts to save them, some of these rescuers may be reluctant to go public out of fear that people will judge them for having harbored Tutsis. Though Rwanda has encouraged reconciliation between Hutus and Tutsis, some animosity still simmers between the two groups.

Despite these ongoing tensions, Burnet’s work reflects a growing conviction—in Rwanda as well as abroad—that there is value in absorbing rescuers’ stories, in understanding how they reacted when they faced stark choices between compassion and survival. In all their messiness and complexity, real-life rescue narratives prompt reflection on the full spectrum of moral choices that people face in extraordinary times—and on the magnitude of the sacrifice people like Felicite Niyitegeka made in order to help their fellow human beings.