Poets Resist, Refuse, and Find a Way Through

A detainee prays in a prison cell at Guantánamo. Rural women in Brazil tend to a bounty of crops, despite threats of expanding agribusinesses. A poet unravels an 1846 British treaty “selling” Kashmir, weaving it into a new form. The poems in this collection attest to the fact that wherever there is oppression, there is resistance. Wherever there is injustice, there is refusal. Wherever power seeks to constrain and dominate, there are ways of forging other paths forward and through.

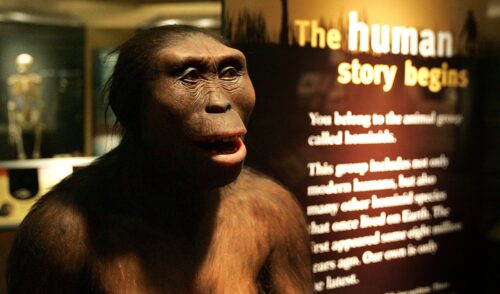

Through these poems, we pull an anthropological lens to our eye to look at critical questions of power and agency. Often, those in positions of power try to sustain and justify their hold by controlling the narrative: They may highlight or disappear certain stories, facts, histories, or outcomes. It can often be tricky to discern how these “games” of power are constructed—to see who pulls the strings or shapes our shared realities.

One way to trace the footprints of power, and the propaganda that upholds the powerful, is to turn our lenses toward what people are resisting or refusing. What are they fighting against? What are they turning their backs on while insisting on a different frame altogether? What might they even be dying for?

Oftentimes, through such lenses we can begin to notice seeds of justice, of future possibilities noticeably hidden by the powerful.

And through poems tracing these footprints, we can feel and experience how people chip away at, push back against, or transform dominant narratives that control and violate—all of which are high-risk acts.

In June 2024, our editorial team put out a call for submissions of anthropological poems of resistance, refusal, and wayfinding. We asked “how poets—informed by anthropological themes and research—can speak to the ways sociopolitical movements and people’s everyday moments resist and refuse as a means to defend or usher in other ways of living and being.”

We were thrilled to receive over 150 poems from a wide range of authors around the globe.

The 12 poems we selected for this collection speak back to power and domination across diverse contexts. They help us track exploitative systems—both large-scale and intimate. These voices are resisting colonization, contesting environmental destruction, speaking with urgency, with joy, despite both overwhelming and banal violence. They reveal the multitude of ways in which resistance, refusal, and wayfinding might take shape.

“Our house / is occupied,” Eric Abalajon writes in “Translation Notes,” which uses testimony notes from a meeting with the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Climate Change and Human Rights where Abalajon served as a translator. Tumandok leaders from Indigenous communities in Central Panay in the Philippines were massacred or arrested in December 2020, and their communities continue to face the threat of displacement due to the construction of a megadam. The poem centers their voices while at the same time, its fragmentation disrupts the business-as-usual coherence of bureaucratic proceedings. Each caesura echoes with a loss, struggles against the sense of not being heard—yet continues to speak, insisting: “report this to others / give justice.”

Don Edward Walicek’s poems in this collection are also in the docupoetry genre, informed by his visits to the U.S. Guantánamo Bay Detention Center in Cuba, conversations with former prisoners there, and documentary analysis. Both “Order for my Backpack” and “Three Stages of Nowhere” use unadorned language to show, with piercing clarity, the mundanity of carceral violence and U.S. imperialism. “An Order for my Backpack,” inspired by Günter Eich’s poem “Inventory,” runs through a list of ordinary items presented for inspection—in seeming compliance with prison protocol—but it refuses the carceral logic of guilt in a way that reveals the violence behind the sheen of institutional order. “And this is a reminder—the list of words / I’ve promised / not to utter,” it reads, followed by those utterances, in simple defiance.

This collection transports readers to varied localities, enclaves, cultures, cities, and battlefields where injustice and oppression are common enemies—and words the firepower.

In other poems, resistance must depart from the ordinary in order to propel the imagination toward radical possibilities that might seem impossible in the face of totalizing oppression. Nadia Said’s poem “Jesus Is Palestinian” is a speculative recasting of a contested icon that affirms the power of solidarity across contemporary experiences of settler colonial and white supremacist violence. Jesus has “woolly hair,” “is lactose intolerant,” and “has learned he must stare straight ahead when pulled over.” The call to recognize the interconnectedness of struggles is made more explicit in “Heaven on Earth,” where Said writes that “they have created hells that used to be heavens of Gaza and Sudan and Congo,” in order “to keep—your heaven running.” Yet, the speculative register is also one that pushes against dystopian reality, where the possibility for change exists like “rain that continued to fall for centuries into the hollows of the earth.”

While resistance can take on different forms, people’s actions and words emerge on their own terms as well and move beyond mere response to domination or oppression. Refusal can come as a rejection of differential power relationships or the terms of these dominant structures. In poetry, refusal can also be expressed as a refusal to provide certain forms of insight or revelation.

“Passing Notes” enacts linguistic refusal in the face of colonization. Melanie Hyo-In Han’s poem is bilingual, containing untranslated lines in Korean, like the secret notes that were being passed by the poem’s Korean subjects who kept their language alive during Japanese occupation. Both Han’s and the speaker’s refusal to submit to linguistic erasure is a quiet yet determined withholding of explanation or clarification for the outsider’s gaze. The poem embodies the tenacity of cultural survival through “the seeds i’d hidden / in the notes i passed / to you in secret.”

Khando Langri’s “Emic/Etic” also refuses to conform to linguistic expectations, here in relation to the academy’s conventions to separate or denote local or “emic” concepts through italicization. Langri’s poem attempts “to compose an anti-glossary,” asking if it matters “who it is that / writes me into being, whose heart / I carry—whose voice.” It speaks back to a key conceptual binary within the discipline of anthropology, separating insider perspectives from outsider analytic frameworks, and proclaims that “when social scientists decreed the body / observable, they made architecture of category.”

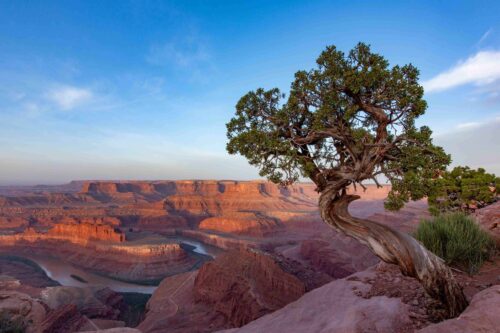

“Pequi Winds” by Jacqueline Ferraz de Lima refuses reductionism and the totalizing story of environmental devastation in central Brazil by giving voice to rural women in Minas Gerais. Through narrative, these women preserve worlds of beauty and nourishment amid the damage of large-scale plantations and—across time and territories—in the wake of Portuguese colonialism and as part of the diaspora. In place, they refuse the logics of agribusiness and instead insist that true wealth comes from a deep attunement to the land and its offerings. With wisdom and perseverance toward creating life, “the same pale mother violet in the middle of / the wasp nest, / has no bordered meaning to form ground / in the thread of time.” Yet, too, the poet reminds us “that silence is also / language / and shared fight.”

Also written against the destruction of ecological habitats, Sneha Subramanian Kanta’s “Broken Sonnets for the Anthropocene” insists that environmental abundance itself is an act of refusal—in disregard for humanity’s terms of engagement. “Across the widening grasses / being replaced by a parking lot, the tree still oozing holy / remnants of fruit,” writes the poet, and the poem itself embodies this refusal-as-abundance, oozing with long lines and lush language. The “speaker of this poem” is an almost disembodied figure, while the reader is left breathless by the density and saturation of the text. We must let ourselves be submerged.

Experimentation with form offers other poets in this collection avenues for wayfinding. Moving from resistance and refusal, these attempts at wayfinding craft ways forward by attending to surprises, ruptures, and buried histories, moving toward new awareness and new language.

In “Debitage,” Jade Lomas generates a new poetic form inspired by archaeological terminology. Debitage are the “debris and discards” of lithic, or stone, tools and weapons. But the word also phonetically evokes the weight of inherited debts, which the poem not so much excavates as chips away at. As lines flake off, the speaker reclaims a sense of agency over a difficult history, undoing the traumas of gendered and domestic violence. In the end, only the speaker remains standing after the disintegration. She reaffirms her voice with the singularity of “i.”

Noland Blain’s autoethnographic-esque lyric “Tallahassee Ghazal” is a turn to an established and beloved poetic form, but here, they play with its traditional use as a love poem. Evoking a heady and heavy mix of fear, boredom, and familiarity that accompanies the speaker’s experience of growing up queer in Florida, in the U.S. South, the poem’s repetition of “town” and “June” reinforces a sense of cyclicity and entrapment. Tightly, these words bracket the couplets. In the end, there is room for a sigh of relief. The poem conveys a deep-seated sense of place and love for that complicated place: “June, and most of us are breathing. This is enough to be proud.”

Finally, Uzma Falak’s two poems (excerpted from a series of six) use erasure as a “site of refusal and of imagining liberatory futures,” as she writes in her notes to the poems. Responding to the colonization and continued occupation of Kashmir, Falak’s fragmentation and textual erasure of the Treaty of Amritsar (March 16, 1846) refuse the British sale of Kashmir and the exploitative capture inherent in colonialism of the past and present day. While the first poem begins with “Treaty / over / for ever / independent / body,” the second emphatically states “hill mountain country eastward westward river / ceded not.” It invites readers to “Sing and March / Our Rubee-ool-awul (first spring)” to make the “future present.” The second poem speaks from an image of an intricate map-shawl of Srinigar, the summer capital of Kashmir and Jammu, evidencing the resistance of said country, river—and its people.

The poems in the collection encourage us to see resistance and refusal as layered acts—both overtly and covertly performed. The political and poetic converge in the landscape of language, form, and expression to show that the quotidian holds as much possibility for resistance as the inflamed moment of protest.

As readers, we anticipate you will be drawn into worlds where there is as much despair as hope—places in which resistance can be a bridge between the two. This collection transports readers to varied localities, enclaves, cultures, cities, and battlefields where injustice and oppression are common enemies, and words the firepower. Each week, a selected poem or pair of poems will be published, inviting you to engage with the crafted work of the spotlighted poet. Each poem contains a unique message, form, and style. We encourage readers to return to the works and follow the different offerings as they are published in the coming months.

Refusal in the face of the powers that be is not an easy task to enact. Black feminist theorist Tina Campt writes of a practice of refusal that reflects the “urgency of rethinking the time, space, and fundamental vocabulary of what constitutes politics, activism, and theory.” The poems in this collection underline this urgency to imagine in especially pressing times. With this collection, a path is charted to the wide horizon of hope, community, and dreaming. These poets highlight the challenges of contemporary existence, and the brick and mortar needed to build a better future.

Join them as they outline new horizons. May their stories of resistance, refusal, and wayfinding inspire you. These are opportune times to be emboldened and comforted by the words of fighter-poets.