How Heavy Metal Fuels Indigenous Revival in Patagonia

I FIRST HEARD Patagonian heavy metal on a cold winter night in Esquel, Argentina. The song roared to life with guitar riffs and drumming resembling a U.S. or European thrash metal record. But around the 35-second mark, unfamiliar wind instruments grabbed my attention. When the vocals came in at just over the 1-minute mark, I was surprised to hear that they were not in Spanish or English but rather the Indigenous Mapudungun language.

“Metal from here is a really beautiful fusion,” Patagonian music expert Rogelio “Lito” Calfunao shouted to me over the music playing in his recording studio. “I don’t know why metal goes so well with Patagonian folklore. Because of the lyrics, because of the rebellion, because of the power … I love this group because they are a clear example of the fusion of metal with ancestral heritage.”

As an anthropologist who studies Indigenous music and language revitalization, I had traveled to Esquel to do just that. This city of 37,000 in Argentina’s Chubut province entered my radar after I connected with Calfunao via his YouTube page Lito Calfunao en Patagonia. A renowned radio operator and promotor of all genres of Patagonian music, Calfunao invited me to Esquel and to Sala Patagón, the recording studio he runs with his wife, Mara Agañarez.

Partway through our conversation on Indigenous history, music, and language, Calfunao lit up when he discovered that we were both metalheads. He eagerly opened his laptop to play a track he recorded two years prior by Awkan, a Patagonian metal band of Indigenous Mapuche origin.

That night in Sala Patagón stuck with me as my dissertation research took shape. I had initially planned to focus on Indigenous language revitalization in public schools, but it soon became clear that spaces like Calfunao’s recording studio carried just as much value for Patagonians looking to reconnect with Indigenous languages and cultures. Specifically, I began to wonder how nontraditional genres like heavy metal music might relate to language revitalization. What could heavy metal provide for those looking to reconnect with their Indigenous heritage in Patagonia today?

I plunged into the world of Patagonian metal to find out.

INDIGENOUS SELF-RECOGNITION IN ARGENTINA

The original peoples of the region today known as Argentine Patagonia include the Mapuche, Tehuelche, and Selk’nam, and their ancestors. The earliest European contact occurred during Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage in the early 16th century, but the lands of Patagonia remained fairly free of outside control until the second half of the 19th century.

Through the violent military campaign known as the “Conquest of the Desert,” the Argentine government gained control over the southern portion of the continent, killing and displacing Indigenous peoples and moving to assimilate the rest through educational and religious initiatives. The national government also incentivized European settlement on these lands, with the goal of economically and ethnically incorporating these territories into the new Argentine nation-state.

In the years that followed, a mainstream historical narrative emerged that represented Argentina as a White nation of European immigrants with no remaining Indigenous peoples. This narrative of Whiteness and of Argentina as the “Europe” of South America persists today, as highlighted in a 2021 speech by then Argentine President Alberto Fernández. “The Mexicans came from the Indians, the Brazilians came from the jungle, but us Argentines came from boats. And they were boats that came from Europe,” Fernández claimed.

While Fernández received widespread criticism for this statement, I regularly encountered this belief from Argentines when explaining my research topic. Mapuche people in particular must deal with narratives that associate the Mapuche with neighboring Chile and incorrectly claim that Mapuche people are not native to what is today Argentina. Mapuche communities aiming to reclaim ancestral territories have routinely clashed with Argentine police, the National Parks Service, and elite landowners. Although the Mapuche have suffered the brunt of the resulting violence, some outsiders have come to view them as threatening “terrorists” pursuing inauthentic land claims.

Indigenous musicians, organizers, and community members must deal with these constant challenges when pursuing political struggles and personal revitalization journeys. Despite this, Argentine Patagonians are increasingly embracing their Indigenous heritage. They refer to this journey as a process of autoreconocimiento, or “self-recognition.” As Esquel-based Mapuche musician Amutuy describes it:

“Today the history of the Native peoples, the history especially of the Mapuche people, is developing in a different way thanks to the new generations who try to maintain the history, to maintain the memory of the many things that have happened to us. I have been in this process of self-recognition for several years. And it never ends.”

PATAGONIAN HEAVY METAL AND INDIGENEITY

Mapuche and other Indigenous musicians in Argentina have drawn on heavy metal to express and reconnect with their Indigenous heritage.

Heavy metal first arrived in Argentina in the 1980s, as bands like V8 drew inspiration from heavy metal scenes in the U.S. and the U.K. Metal was initially centered in the capital of Buenos Aires, but as bands began to tour the Argentine interior, they introduced metal to new regions, including Patagonia. During my fieldwork, I learned that working-class Patagonian musicians found heavy metal to be a powerful way to articulate their discontent with economic struggle, out-of-touch governments, Indigenous erasure, and the isolation of their region from the rest of the country.

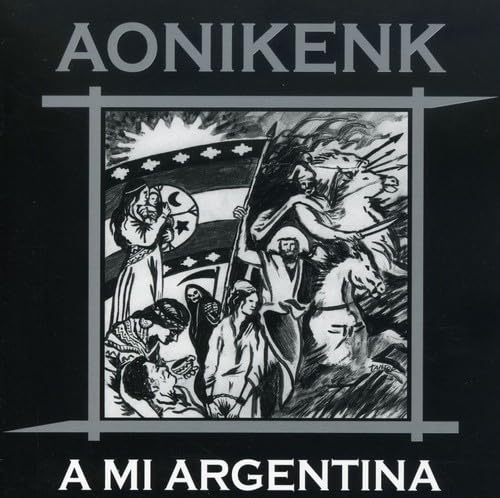

Since the late 1990s, a unique genre known as metal patagón, or Patagonian metal, has emerged in southern Argentina that brings together Argentine national metal with folklore music from the Patagonia region. Early Patagonian metal bands such as Aonikenk, Razzia, and Werken established the importance of Indigenous peoples to Patagonian history and culture in their music. The bands played distinct styles of metal but shared a commitment to Indigenous themes and aesthetics in their lyrics and presentation.

While these bands wrote lyrics primarily in Spanish, they drew on Indigenous languages, particularly Mapudungun and Tehuelche, for band names, song titles, and, occasionally, song lyrics. The band name “Werken,” for example, refers to a traditional messenger and spokesperson role in Mapuche society.

Patagonian metal bands also began to draw on Indigenous imagery in band logos, album art, and merchandise. Common symbols included the Mapuche flag (wenufoye), arrowheads, the kultrun drum, and Indigenous warriors on horseback. In tandem with their lyrics, this imagery instantly identified the bands and the genre with Indigenous peoples and causes.

Starting in the 2010s, bands such as Awkan and Neyen Mapu drew inspiration from these earlier bands while connecting their music more directly to a concrete Mapuche identity and specific political causes. Awkan, meaning “warrior” or “rebellion” in the Mapudungun language, is unique in that they write some songs entirely in Mapudungun. The band also uses native instruments such as the trutruka (a reed trumpet) and the pifilka (a stone or wooden flute) alongside the more typical heavy metal instruments of guitars and drums.

Awkan’s music directly takes on topics affecting local Mapuche communities. On the track “Lonko che,” for example, they tell the story of Mapuche community Paineo las Coloradas’ resistance to a proposed open-pit mining project on ancestral lands. Mapuche communities like Paineo have consistently fought against extractive projects like this one due to the threat posed to Indigenous sovereignty and local waterways and soil. Anti-mining organizing has become a defining feature of Indigenous politics and is a frequent topic in Patagonian metal songs.

The band Kelenken, named after a Tehuelche mythological figure, also employs Mapudungun as well as Tehuelche in album and song titles. This band is known for their use of native instruments, such as the trutruka and the siku (panpipes), and for incorporating Indigenous rhythms and time signatures that are unusual for heavy metal.

In Kelenken’s song “Marichiwew,” whose title refers to an iconic Mapuche chant and war cry, the band draws on the loncomeo rhythm. This Mapuche rhythm is traditionally played on the kultrun drum and accompanies dancing during the camaruco, the most important Mapuche religious ceremony. The band has adapted the loncomeo to a heavy metal context through interpreting it on a drum set and playing with the tempo. Like Awkan, Kelenken’s lyrical content has taken on Indigenous history and contemporary struggles, and the band frequently draws on imagery such as Mapuche and Tehuelche flags, musical instruments, and textile patterns.

While each of these bands takes a different approach to heavy metal music and Indigenous issues, they share a commitment to telling Indigenous stories and establishing Indigeneity as a key part of Patagonian and Argentine history. For many Patagonian metal musicians, there is also a personal element of reconnecting with one’s Indigenous identity through the process of autoreconocimiento.

For Kelenken’s guitarist, Ema Montecino, the journey began with reconnecting with his ancestors and learning about his origins. He told me he wondered how he could contribute to Mapuche culture in a meaningful way as an urban Mapuche with limited ties to Native lands.

“I wasn’t going to reclaim a piece of land,” he said, “because it wasn’t mine.” But he realized he had the strength “to reach people through a microphone, through a song.”

Music became his way to carry the fight forward. Ema’s work resonates with others in the Mapuche struggle—those reclaiming lands and advocating for justice. His music has inspired people to assert, “This land belonged to my ancestors, and it has to be free again.”