Zika at the Rio Games: Pandemic or Panic?

Earlier this year, a group of international scientists wrote an open letter to the World Health Organization (WHO) calling for the Rio Olympic Games to be postponed or moved due to the ongoing Zika virus epidemic. “An unnecessary risk is posed when 500,000 foreign tourists from all countries attend the games, potentially acquire that strain, and return home to places where it can become endemic,” the letter argued. The protest letter, which as of August 6 bore 240 signatures, called the WHO’s support of holding the games on schedule unethical and irresponsible, and asserted that the organization’s close relationship with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) constituted a conflict of interest. The WHO issued a statement that “there is no public health justification for postponing or cancelling the games.”

There has been surprisingly little research on the spread of epidemics from mass gatherings, yet the few studies that have been done on the topic hint that the risk is miniscule. From an anthropological perspective, the massive measures taken to minimize security risks and disease transmission at the Olympics are really just a kind of ritual, designed to provide the illusion of safety, control, and order. Given all of this, and the chance of a pandemic arising by other means, far too much money and effort are perhaps being poured into an irrational panic about the disease at the games.

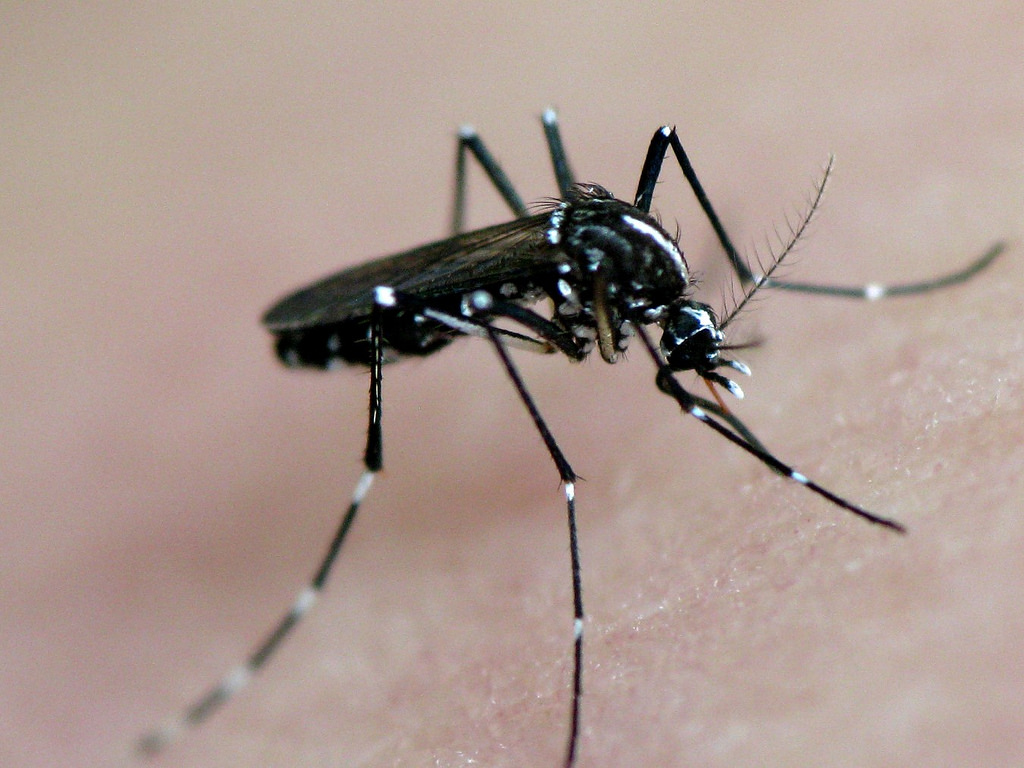

The Zika virus itself is not as lethal as Ebola, which often brings swift and painful death, or SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which has a 10 percent fatality rate. The most common symptoms of Zika—which is mainly transmitted through mosquito bites, from mother to child, and sometimes through sexual intercourse—are fever, a rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis. About 80 percent of infected people will have no symptoms at all. Niko Besnier (one of the co-authors of this piece) contracted the virus during fieldwork in Tonga in April 2016, but his mild rash disappeared within 48 hours. What started to alarm the experts was a rise, at the end of 2015, in the number of babies in Brazil born with microcephaly (small, malformed heads) and other severe brain defects. In April 2016, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) affirmed that Zika infections in pregnant mothers were the cause.

Some scientists originally blamed sports events for the introduction of the Zika virus into Brazil in the first place. They hypothesized that it had been brought by teams arriving from the Pacific Islands in 2014 to take part in the FIFA World Cup football (soccer) tournament or the Va’a World Sprints Championship canoe race. However, an international team that sequenced the Zika genome estimated that the virus had been introduced from the Pacific Islands in the second half of 2013. Although they couldn’t rule out the FIFA Confederations Cup football tournament as the initial point of transmission, the researchers noted that Brazil had seen a general increase in flights from Zika-infected countries in the second half of 2013.

One challenge for scientists is that the relationship between mass gatherings and communicable diseases has only recently received serious attention from the WHO. In the wake of the SARS epidemic in China in 2003, the WHO devoted increased resources to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, producing its first handbook on public health for mass gatherings (revised in 2015). Before that, medical surveillance at Olympic Games was largely left to local health authorities with little international input.

In 2010, the WHO found an ally in the government of Saudi Arabia, which oversees the world’s largest annual mass gathering—the Hajj, which dwarfs the Olympic Games in attracting several million pilgrims from some 180 countries over a five-day period. That gathering has led to the spread of disease before: there have been several instances of pilgrims taking meningitis back to Europe, one of which resulted in 14 deaths in 2000. In 2010, Saudi Arabia’s then deputy minister of health organized a meeting of 500 experts that led to the creation of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Mass Gatherings Medicine.

The 2012 London Olympics further advanced the development of new medical surveillance practices. In advance of the games, a “syndromic surveillance system” conducted daily reviews of reports of infectious diseases coming from across the UK. The surveillance team discovered that the existing data didn’t provide daily information from “out of hours” visits to general physicians, or visits to walk-in clinics and emergency rooms (precisely the services that overseas visitors use). This was corrected in the surveillance done during the games and was subsequently incorporated into the standard surveillance routine. More rapid laboratory diagnostic tests were also implemented. In the end, no major health incidents occurred at the London Olympics. A staff member who was interviewed for a qualitative evaluation of the program observed, “It was all a storm in a teacup.”

There is no solid scientific evidence that a vector-borne disease like Zika has ever been spread by a mass gathering.

A 2009 review of the literature covering surveillance of infectious diseases at mass gatherings—including several Olympic Games as well as FIFA World Cup and EURO football tournaments held between 1984 and 2006—documented not a single case of an increase in infectious diseases at major sporting events. Having looked at the data, the paper’s author felt it was legitimate to ask, “why bother?” with expensive surveillance.

In a June 2016 review of 68 studies on communicable-disease spread at events ranging in size from 350 participants to several million, researchers noted that “there may be an unexpected gap between forecasts and reality.” Major outbreaks at such events have been very rare so far. The most common large-scale outbreaks, which have sometimes affected several thousands, have been measles, influenza, mumps, and hepatitis A—all of which are largely vaccine-preventable—in addition to gastrointestinal infections from unsanitary food preparation. There is no solid scientific evidence that a vector-borne disease like Zika has ever been spread by a mass gathering. While carriers have taken infections back to other countries, the numbers of people affected have always been very small. Major sports events seem to spread even fewer communicable diseases than large-scale religious events and open-air music and art festivals, in which throngs may be pressed together in an open field with rudimentary sanitation facilities.

One can see how fears of pandemics spurred by the Olympics arise. The thought of half a million foreign visitors converging on the epicenter of a little-understood illness is scary. But that perceived threat has to be tempered. Because other tourists tend to avoid the flood of visitors expected to converge on a city during the Olympics, the Summer Games usually reduce the overall influx of tourists into a host city, both during the event and over the entire year. Since many residents leave town or curtail their normal routines, there may be fewer people than usual in public areas outside designated Olympic sites.

Another study published in June by 13 researchers based around the world observes that far fewer visitors will come to the Rio Games than routinely visit the more than 60 Zika-endemic countries. The authors conclude that cancelling the games would have no measurable effect on the spread of the virus, stating that “the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro should not be canceled.”

Despite all the evidence, great amounts of funding, preparation, and media chatter has been devoted to Zika because sports mega-events are theoretically ideal for the spread of infections, although they rarely actually spread infections. Even if the risk is infinitesimal, government officials and event organizers must produce the appearance of concern and preparedness to cover themselves if the unlikely event occurs.

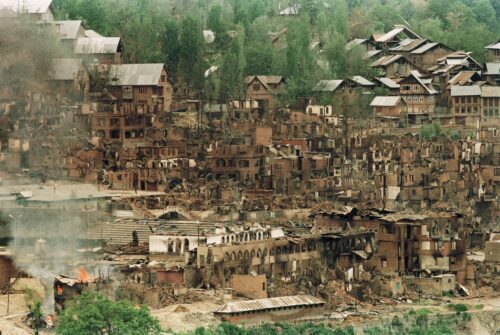

The heavily publicized security measures around Olympic Games are rituals that provide reassurance in the face of unpredictability. For example, the urban renewal that preceded the London Olympic Games can be understood as a cleansing and purifying ritual that projected an image of order and control onto the normal chaos of urban life. Anthropologist Vida Bajc coined the phrase “security meta-ritual” for such attempts to control uncertainty in potentially catastrophic situations. From the point of view of the surveillance and security apparatus responsible for the Olympic Games, everyday life itself is considered dangerous and uncertain.

Olympic Games have strengthened collaborations between different levels of governments and international health organizations. They have led to the development of new laboratory technologies, information-gathering procedures, and statistical methods. Most importantly, they have pushed forward the design of more comprehensive surveillance systems that combine all of these. But these developments are a double-edged sword.

Zika is already affecting Brazilians unevenly, according to anthropologist Erika Robb Larkins, who has been conducting fieldwork in Rio 2016’s security command center. Larkins observed that Zika is more prevalent in the poor areas where there is standing water and where many people don’t understand the disease. Mosquitoes do not generally fly very high, which means they are less likely to reach upper-level apartments that are more expensive because they have the best views. Some middle-class women who are pregnant and can afford to leave the country are doing so, while others are choosing not to get pregnant. “Poor women are not in conditions to be planning their pregnancies in the same way,” Larkins told us. Still, some Brazilians feel the alarm is exaggerated. Men and poor people who are not having kids are not so worried. On the whole, Larkins said, “The Brazilians seem to find the concerns ridiculous, gringo-esque fears.”

The great amount of pre-event forecasting, theorizing, preparation, and expenditure is disproportionate to the minimal risk of communicable diseases being transmitted at major sporting events. The likelihood that the games will spark a pandemic is miniscule, while the likelihood that a pandemic will come from a completely unanticipated source is very high. The panic around the Olympics has diverted too much taxpayer money and government attention into monitoring an event that is almost certain to be largely harmless.

Niko Besnier’s research for this article was funded by the European Research Council. Susan Brownell’s research was funded by the College of Arts & Sciences and the Office of International Studies and Programs at the University of Missouri, St. Louis.