Your Olympic Team May be an Illusion

This story is part one of a five-part series that explores the culture, politics, economics, and more behind the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic Games.

The parade of athletes in the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games often evokes strong feelings of national pride. After the 2012 Summer Games in London, the Armenian National Committee of America sent a letter of protest to NBC’s CEO and president, Stephen Burke, to complain about the short shrift Armenia received from the commentator, who only said four words about their country: “Armenia, now walking in.” Their grievance paled, however, in comparison to the Olympics-related protest that took place in 1996. Thousands of Chinese people and organizations in the U.S. and elsewhere collected US$21,000 to buy advertisements in prominent newspapers protesting the fact that NBC commentator Bob Costas mentioned human rights abuses, doping allegations, and property rights disputes as the Chinese delegation entered the stadium for the parade.

About a billion people are expected to watch the opening ceremony of the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games on television on August 5. For most people, the highlight will be watching their country’s athletes walk proudly into the stadium behind their national flag.

The parade of athletes displays a neat world order filled with proud, loyal citizens. But nations are not really the clear political units presented in this happy family portrait. Beneath the surface is a mess of transnational wheeling and dealing by power brokers as well as athletes seeking to get the most reward for their hard work and talent—for themselves and for their families and friends.

In the last few years, well-heeled Persian Gulf states have attracted athletes from other countries by offering them money, training facilities, and the possibility of qualifying for the Olympics more easily than in their home countries. The diminutive but oil-rich emirate of Qatar, for example, has until now played a very modest role in world sports. But in recent years the country has made huge investments in sports and adopted a liberal citizenship policy for athletes. The Qatari national handball team, which reached the finals at the men’s 2015 Handball World Championship, had only four players originating from Qatar on their 17-person squad—the rest had been recruited from overseas. By our calculation, more than half of the 38 athletes who will represent Qatar in Rio were born elsewhere.

Bahrain earned its first Olympic medal in 2008 when Moroccan-born Rashid Ramzi won the gold in the men’s 1,500-meter race (an award that was later rescinded due to a positive doping test). In 2012, Maryam Yusuf Jamal, previously from Ethiopia, won a bronze medal for Bahrain in the women’s 1,500. Bahrain is sending its largest-ever contingent (30 athletes) to Rio, including track and field athletes born in Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Jamaica, and Morocco, as well as a weightlifter who is originally from Russia. Only four of the country’s athletes were born in Bahrain.

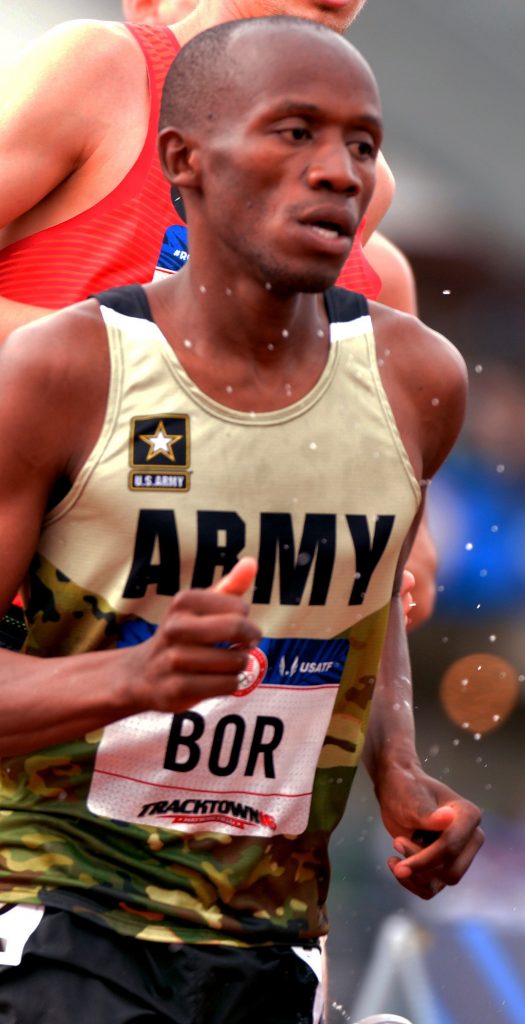

It is not just countries with limited local talent that are spending their way to winning teams. The United States, with its deep sporting traditions and its giant talent pool, has fast-tracked citizenship for some athletes who will be in Rio. Elite athletes who are in the U.S. Army can qualify for the World Class Athlete Program. Because the program involves enlisting in the U.S. Army, athletes who were born in other countries do not have to comply with the normal five-year residency rule that is strictly upheld for all other immigrants seeking citizenship (an exemption was implemented for soldiers after 9/11). The U.S. track and field squad going to Rio includes four Kenyan-born athletes who benefited from this program.

China, which has recently emerged as a sports powerhouse, is sending an increasing number of athletes out into the global marketplace. It dominates table tennis to a greater extent than any other country in any other Olympic sport—its athletes have won 24 of 28 gold medals since table tennis became an Olympic sport in 1988, including all of the gold medals in 2008 and 2012. Many players who have no hope of making Chinese national teams are now being driven to other countries: of the 140 singles table tennis players who have qualified for the Rio Olympics, 27 were born in China but will represent other countries. Brazil will be represented by Chinese-born Lin Gui, who immigrated at the age of 12 to play and was naturalized at 18—just in time to represent Brazil at the London Olympics.

This transnational mobility touches a sensitive chord. Some critics question why athletes should have an easier path to citizenship than other immigrants. Others paint the athletes as greedy money-grubbers or as turncoats who have betrayed their nation of origin.

Ever since modern sports were invented in 19th-century Europe and North America, the lofty ideals of fair play, allegiance to country, and financial disinterest have played prominent roles in sport. This has a lot to do with the fact that many sports were originally played by wealthy ruling elites whose detachment from financial concerns came easily and whose attachment to the country they ran was understandable. Despite the enormous transformations that most modern sports have undergone over the decades, these values continue to persist—and to uneasily rub up against the huge incomes earned by elite athletes in some sports and the ease with which they now switch countries.

What has happened leading up to the Rio Olympics is merely an example of practices that permeate global sport as a whole. Team sports with vast global audiences, such as football (soccer) and rugby, experienced a spike in athlete mobility starting in the 1990s when the revenues from TV rights skyrocketed, some clubs and teams became for-profit corporations, and the salaries and transfer fees of athletes began to increase dramatically. Faced with increased competition, clubs and teams began searching for talent further and further afield. Many football clubs established academies in countries like Kenya or South Africa with the goal of identifying and recruiting talented youngsters before other clubs could get their hands on them, and perhaps before the athletes realized what they might be worth.

Some have bemoaned the resulting “brawn drain”: the depletion of athletic talent from the poorer “global south” for the benefit of the richer “global north.” For some, this looks like a repeat of the unfair practices of yesteryear, when the colonized world supplied commodities and labor to the colonial powers. But others see it differently. Fiji, for example, has many talented rugby players but little money to support a rugby infrastructure of international quality; its most talented players often seek contracts in other countries. But Fijian rugby fans don’t see this as a problem. They cheer for whatever overseas team counts Fijian players on its squad.

Many of the athletes imported from the global south send their money back home. They often carry on their shoulders the hopes of many for a better life. Niko Besnier (co-author of this piece) became well-acquainted with a professional rugby player from Tonga who was playing in Japan. The man estimated that, at the time, 70 people in his island country were financially dependent on him. Another up-and-coming young rugby player from Fiji on contract with a French club was sending all of his modest salary to his demanding relatives every month—leaving him no money whatsoever for his own sustenance—until the team’s French support staff intervened.

Sport offers opportunities to escape poverty and build a better life. But it is important not to lose sight of the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that helps to open these doors. Qatar’s sports empire was built by one faction of the country’s royal family, as part of a two-pronged strategy to consolidate its hold over the government and increase its influence on the world stage. The strategy paid off when the current emir assumed power upon his father’s abdication in 2013. In another case, Susan Brownell (the other co-author of this piece) was told that sports insiders in China wondered whether Kazakhstan, a rising Asian state with Olympic ambitions, gave money to officials in China’s General Administration for Sport to import the two Chinese female weightlifters who won gold medals for Kazakhstan in the London Olympics.

In reality, many “national” teams are a conglomeration of international talent, at times acquired via corruption and political power struggles, and made possible by the vast wealth inequalities between the economic powers and the developing world. If the public understood this fact better, it might help build a stronger sense of global community. Given that the nation-state was responsible for a century of history’s most brutal wars and appalling crimes against humanity, we would all be better off if we jettisoned our nationalist worldviews. The Olympic Games are a good place to start.

Niko Besnier’s research for this article was funded by the European Research Council.