The Big Business of Europe’s Migration Crisis

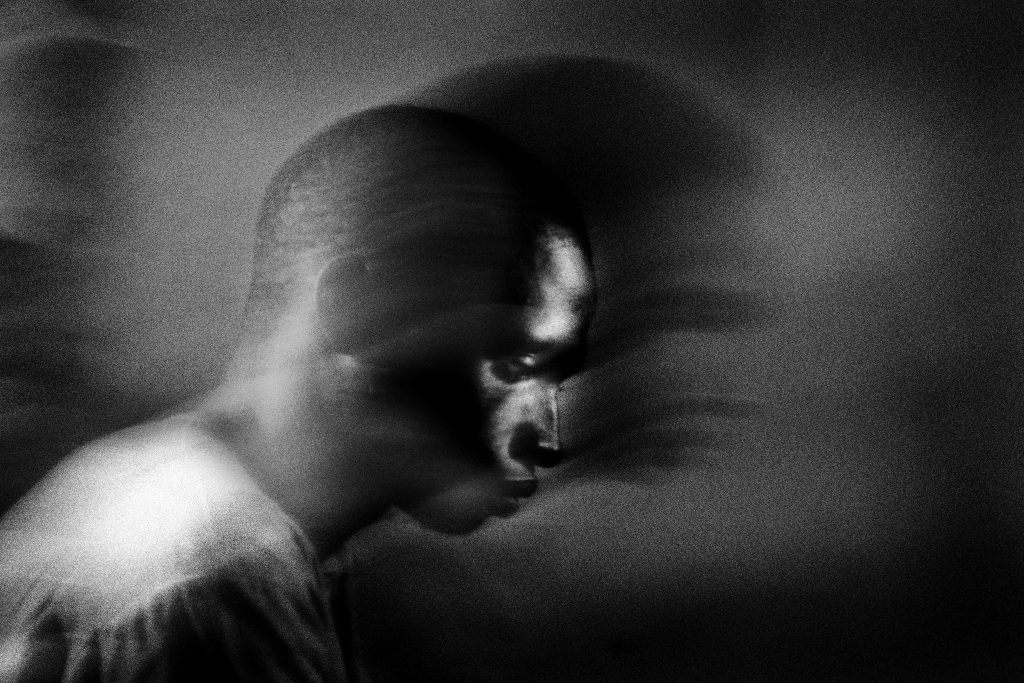

After three months in Rabat, the capital of Morocco, Famara (who requested his last name not be used) left for the Gourougou mountain forest of northern Morocco. Wearing nothing more than shorts, a blue jean jacket, and flip-flops, the diminutive Senegalese man joined a makeshift camp comprised of dozens of West Africans hiding in the mountains between the town of Nador and Spain’s North African city of Melilla. Stays at the camp were temporary. Those with opportunities to move on did so while new migrants making their way north arrived daily. Many in the camp were injured, and all were hungry. None were prepared for life in the woods.

“We didn’t have anything to eat. No way to wash. We slept outside,” Famara texted to me in French. “Every week the Moroccan police came. They beat us, burned our camp, and took our bags. It was not easy to live down there. My money was finished and I was digging in the trash to find enough food to eat at times,” he continued. Occasionally, Famara left the mountains to find help in Nador. “Sometimes I waited at the door of the supermarket to ask if I could help carry people’s bags for them so that they would give me food. But not everyone would help because they were afraid the police were watching me. On Fridays I waited at the door of the mosque to beg for some money. We were just waiting for the right time to go,” says Famara, who was 21 years old at the time.

It was 2011. As the oldest child in the family, Famara felt a responsibility to his widowed father and his siblings. His mother had died in 1994, which left his father, a shopkeeper, on his own to raise his sons. Recently out of school and seeing few, if any, employment opportunities, Famara set off alone from Touba, Senegal, in February 2009 to find work in Germany. “I talked to my father and said I would go,” says Famara. “But he told me no. One day I left without telling anyone. I had 80 euros in my pocket. I had no visa. I was a clandestino,” he says, using the Spanish word for illegal migrant.

Famara is one of hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees who are leaving their homes for a chance at a better life in Europe. For many West Africans, Europe’s allure is the opportunity simply to work. Crushing poverty in the deserts of the Sahel and a declining fishing industry (blamed in part on overfishing by European fleets) leave little opportunity and few job options for young West Africans. In the Middle East, war is driving people from their homes and onto the road to Europe. Syrians, Afghans, and Iraqis look to Europe as the only safe place to escape the violence engulfing the region. Yet such crossings are grueling—and often deadly.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), an intergovernmental organization, 214,691 migrants and refugees have arrived in Europe by sea and another 7,457 by land between January 1 and June 19, 2016. The IOM also counts at least 2,859 dead or missing, many of whom are thought to have drowned. In April, an estimated 500 people drowned when their boat capsized while crossing to Italy. And in May, more than 700 migrants are believed to have drowned in just one week after three separate boats carrying migrants from Libya sank in the Mediterranean. The dangers of the crossing to Europe aren’t lost on those who attempt it, which speaks volumes about their desperation.

Along with the inherent hazards of sea crossing, migrants’ path to Europe is marked by a minefield of obstacles intended to keep them out. The human rights advocacy organization Amnesty International refers to this system of barriers as “Fortress Europe.” Its seemingly impenetrable array of razor-wire fences, naval blockades, drones, and command centers are at the heart of the European Union’s immigration policy. It is a policy, says Ruben Andersson, a Swedish anthropologist based at the London School of Economics and Political Science, that doesn’t work.

“The multifarious agencies purportedly working on ‘managing’ illegality in fact produce more of it,” Andersson wrote in his 2014 book Illegality, Inc., an ethnography documenting his fieldwork among both migrants and those trying to prevent clandestine transit to Europe. Andersson maintains that the EU’s migration management is an “illegality industry” that manufactures what it is meant to curb.

Andersson’s anthropological fieldwork predated the current influx of Middle Eastern war refugees to Europe by a few years. His work spans from 2005 to 2014 and focuses on the travails faced by West African migrants making their way northward to Europe through the North African desert. The current crisis created by the bloody wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, among other countries, exists against a larger backdrop of what Andersson calls the “perpetual emergency” of the EU’s ongoing and unresolved immigration crisis. But the lessons he has learned apply to both the influx of West Africans and those coming from the Middle East.

“If the conflicts and insecurity besetting Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan ended, of course we would see a shift downwards in numbers at Europe’s borders. … But the question of whether we’d see an end to the migration crisis is complicated,” says Andersson.

Over the past 25 years, Europe has invested in an expensive, militarized, high-tech external border control system. Yet, desperate people continue to land on the continent’s shores. Thousands die trying. Europe’s attempt to manage its external border has failed—but European politicians still continue to pursue the same futile strategies, says Andersson. Now he and an increasing number of legal experts and human rights organizations are urging European countries, as well as other rich nations faced with a similar situation, to look at the border conditions with fresh eyes. Their hope is to find a workable, more humane solution for the tens of millions of people on the move around the globe.

In dusty sub-Saharan towns such as Touba, where Famara grew up, and in the fishing villages being swallowed by the sprawl of cities like Dakar, EU funds flow to various nonprofit organizations tasked with discouraging would-be migrants. Some of these organizations are staffed by mothers who lost sons on the journey north or by young men who didn’t make it to Europe. Many of the men relay tales of nightmarish hardships on the road north, the improbability of success, and the shame of failure when they return home. Still other organizations promise paid work to young men who are considering the trip to Europe.

The efficacy of these programs remains unclear, but one thing is certain: People are still leaving for Europe, hopeful for a better life. Once on the road, African migrants endure what can often be a years-long cat-and-mouse game with African police—subsidized by the EU—whose goal is to identify “candidates for illegal migration,” writes Andersson.

For Famara, it took two years to reach the Mediterranean. Famara dodged the Mauritanian police, who he says target migrants heading north, by taking a job as a bricklayer in Nouakchott, Mauritania’s sprawling capital city. Famara worked 11 hours a day for what amounted to 3 euros. “One day I called my father. He cried and told me to come home,” Famara recalls. “But I couldn’t. There is no way to survive at home.”

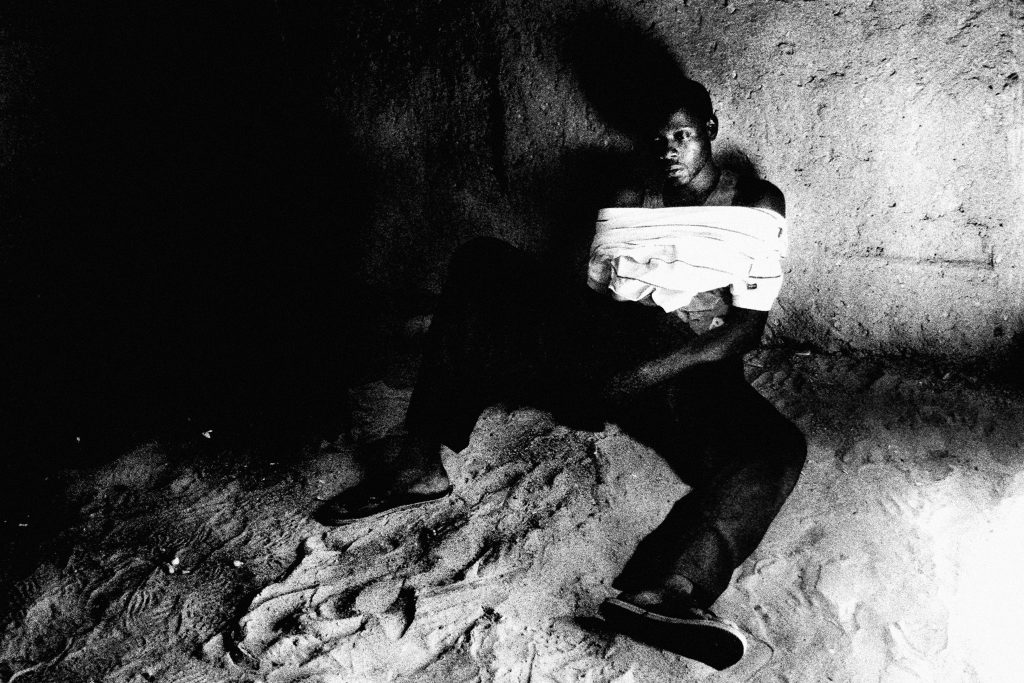

In the Saharan hinterlands, the citrus groves of Morocco, and the ghettos of northwest Africa’s cities, local, EU-subsidized police officers patrol a fluid borderland populated by a spectral threat. North and West African cops are often unable to distinguish Europe-bound migrants from local or regional businesspeople, religious pilgrims, traders, and the irregular workers who have traditionally moved quite freely throughout the region. As a result, authorities sometimes rely on the body language and the presumed intentions of those they hunt, creating a state of “being illegal” even in cases when in fact no crime has been committed, says Andersson.

How much the EU pays non-EU border nations such as Turkey, Ukraine, Morocco, and Libya to help stymie the movement of migrants on their way to Europe proper is unclear. But between 2007 and 2013 one such program had a budget of 384 million euros for migration-related activities, according to Amnesty International. (At the current exchange rate, this amount is equivalent to US$437 million.) This subcontracting of migration control heightens tensions between and within African nations as well as among ethnic groups, Andersson’s research shows. For instance, in Mauritania, darker-skinned sub-Saharan individuals have been identified as supposed “illegal migrants” based solely on the color of their skin, “adding a tinge of illegality to the politics of skin color,” writes Andersson in Illegality, Inc.

Amnesty International worries that payments intended to halt the flow of migrants to Europe may in fact fuel human rights abuses by the governments that receive the money as well as deprive migrants of the due process they are entitled to by international laws, says Gauri van Gulik, Amnesty’s deputy director for Europe and Central Asia. “The clearest example of this today is in Turkey, where authorities pick up refugees—locking them away—or bus them to the southeast border,” says van Gulik. “It is clearly related to EU pressure.”

In November 2015, the EU initiated an agreement to pay Turkey 3 billion euros to stem the flow of refugees. Soon after, Turkey was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for the inhumane treatment of a Russian national asylum seeker. In March 2016, yet another EU-Turkey agreement was signed, this time allowing the EU to ship migrants back to Turkey. While the deal is already teetering, people keep departing on the other key route into Europe, via Libya. “Many people understand the risks they are taking when they cross the sea, but many also regard the risk of dying while trying a better option than the risk of staying and losing their future,” says a spokeswoman for the aid group Mercy Corps.

For some corporations, Europe’s border control also means big business—billions of dollars, writes Martin Lemberg-Pedersen of the Centre for Advanced Migration Studies at the University of Copenhagen. Financial interests help keep this system in place, says Andersson, as many sectors—including both defense companies and border agencies—benefit from the status quo.

Andersson began his research by looking at the effect of border controls on individual migrants. His focus was narrow. But his initial informants—Senegalese travelers who had been deported from Spain—were less troubled by the border controls than they were by “the big gains that they said others were making from their misfortune,” he says. This discovery encouraged him to redefine his research and to shift his focus to those who benefit from migration.

The migrants are well aware that certain players are benefiting from their misery. “They eat of us,” one Senegalese migrant told Andersson, expressing his awareness that the “illegality industry” profits at the migrants’ expense. “To the [Senegalese] migrant and his friends, these winners included not just border guards, defense companies, and the paid-off Senegalese state, but also the aid organizations, journalists, and even academics who, in their view, had all jumped on the migration gravy train,” says Andersson.

Human smugglers, too, end up as one of the biggest beneficiaries of tighter border controls, says van Gulik. As easy routes into Europe are cut off, migrants hire smugglers who promise to get them around or through the walls of “Fortress Europe.” Famara recalls hearing the name of a Moroccan smuggler and moving on to find him, going by boat from Nouadhibou in Mauritania to Morocco’s capital, Rabat. There he survived by washing car windows on the crowded streets until he had enough money to pay the smuggler. Not only has demand increased but, according to Andersson, military and policing efforts to go after smugglers have contributed to raising the price that smugglers command for the transport of migrants. Traffickers and smugglers also sometimes hold migrants hostage for ransom. Many migrants are exposed to sexual assault and violence. Some are sold into prostitution rings.

Famara recalls the night in September 2011 when a man came to his hideout in the Gourougou forest and told the shivering migrants that it was time. They had been waiting in the chilly mountain canyons for three months. Their smuggler took them to the shore of the Mediterranean. The migrants, about 100 of them, crowded into two tiny rubber vessels for the crossing.

Somewhere along the way the boats became separated and the craft Famara was in sank. Famara wasn’t sure why, saying only that the boat “was pierced.” He never found out what had happened. The passengers splashed into the sea and were separated. It was dark, and he didn’t know where they were. “We did not have life vests. We had nothing to protect us,” he added. Famara spent the next 15 hours in the cold waters off the Spanish coast. By the time the Spanish Navy found him, three of his best friends were dead. “I was thankful to be alive,” he says. “But I lost my friends.” The Spanish took him to a migrant processing facility in Algeciras, where he spent the next month. When he was released, a friend invited him to stay at his place in Madrid.

Today Famara lives in a Madrid apartment he shares with six other migrants. He ekes out a living selling bags to tourists on the Puerta del Sol. His life—the life he imagined anyway—is still on hold. “It makes me very sad to talk about this story because I have lost too many friends,” he texted when I checked in on him recently.

The crisis of migration is global. But as Andersson’s work illustrates, the movement of human beings across borders need not be a crisis. It is a problem with viable solutions.

In 2015, slightly more than 1 million migrants entered Europe by sea, according to the IOM. While 1 million is a staggering number, it is much less than 1 percent of Europe’s total population of about 740 million. Andersson says Europe’s migration problem—even in this time of crisis—is hardly a tsunami, as some critics of migration have characterized it. A wealthy continent like Europe should have no problem integrating that number of people, Andersson says. “The vast majority of refugees today are hosted by poor nations, not Western states.” Amnesty’s van Gulik agrees: “Europe is simply not carrying its fair share.”

“We are talking about desperate people here,” says Andersson. Stringing up new fences, building detention facilities, and bribing African forces are concrete things that politicians can do, he says. But such measures deal with the symptom, not the cause. “The search for a quick fix is the problem. The emergency attitude we’ve employed has only led to more emergency.”

Andersson suggests that instead the EU should normalize migration and give people legal, safe, and efficient pathways through which to move. Worldwide, he says, we need an “overarching political strategy that takes into consideration the globalized nature of human movement.” Thomas Spijkerboer, professor of migration law at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, agrees. “There has to be an alternative reading of the current situation if we want a better outcome,” says Spijkerboer.

That requires a tremendous shift in thought around the world, adds Andersson. “Ultimately, we need to unfence migration.”