Why the “Big, Beautiful Wall” Is Doomed to Fail

When Donald Trump announced in June 2015 that he was running for U.S. president, he said, “I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words.” On January 25, 2017, less than a week after taking office, President Trump moved to make good on (at least part of) that promise by signing an executive order for “the immediate construction of a physical wall” along the U.S.-Mexico border. But despite months of media coverage about Trump’s plan to build his “big, beautiful wall,” little news has focused on the fact that the U.S. has already walled hundreds of miles of the border, an effort that has accomplished virtually none of its stated goals.

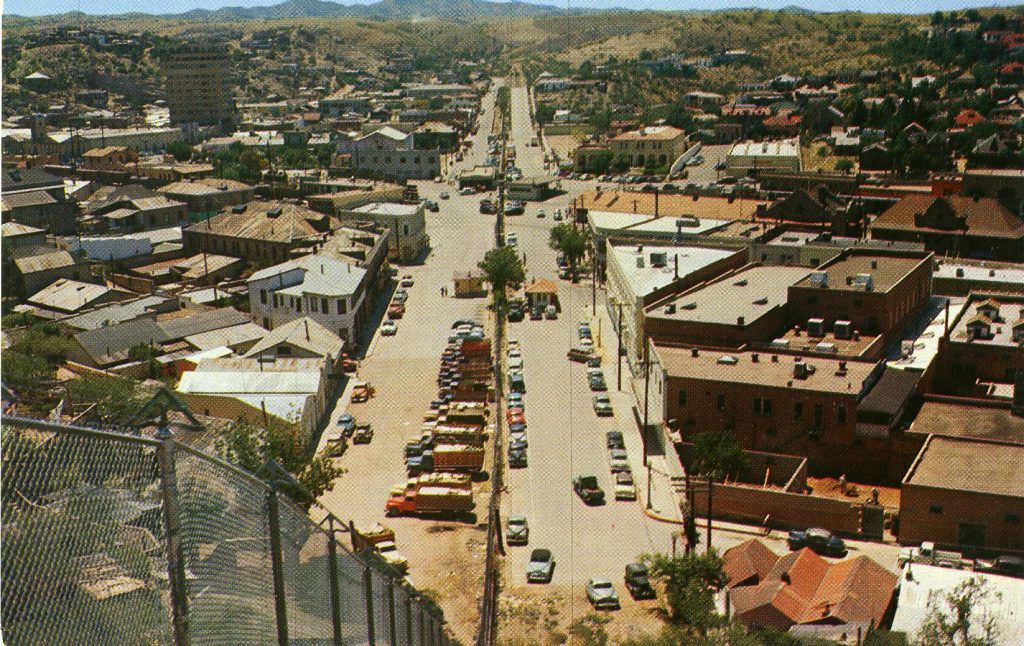

Since 2011, we’ve been studying the 2.8-mile stretch of existing wall in Ambos Nogales, which means “Both Nogales,”—that is, the border towns of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. Initially constructed in 1994, and then rebuilt in 2011, the border wall between the two towns was erected and paid for by the U.S. Many Americans conceive of the U.S.-Mexico border as an absolute boundary that can be fortified and enforced to keep “them” away from “us.” But our experience and study of the wall in Nogales suggests that a physical wall—no matter how high, no matter how intensively militarized—cannot and will not stop the flow of people, materials, and ideas across this politically constructed boundary.

I (Randall McGuire) first encountered the border between the U.S. and Mexico in 1972, when I drove a sputtering Volkswagen bug through Ambos Nogales on my first trip to Sonora. Since then, I have crossed the border at Ambos Nogales hundreds of times—sometimes as a tourist, but mostly as an archaeologist traveling to and from my research area in northern Sonora. Starting in 2008, I began working with the humanitarian group No More Deaths to provide aid to people recently deported from the United States to Nogales, Sonora. In 2011, Ruth Van Dyke (my wife and co-author) joined me.

The border wall loomed over the aid station where we worked, and our daily experience of the wall inspired us to begin applying archaeological techniques and insights to study it. For the past six years, we have been analyzing the Nogales wall using tools from the growing field of contemporary archaeology, which applies archaeological methods and understanding to modern artifacts, structures, and places. Our findings demonstrate how the border wall is the physical incarnation of a violent, even racist, U.S. political ideology that breaks bodies and destroys lives, but also how, like those policies and ideas, the proposed wall is doomed to fail.

The physical border at Nogales has a life history. We have dug through archives for old photos, read newspaper accounts of the wall from different times, and used other historical documents to reconstruct this life history. We have systematically photographed the changing forms of the wall and the graffiti and art installations that people placed on it. We’ve walked along the wall on both sides of the border, crossing at all of the ports of entry, and observed how others interacted with it. And we have also talked to long-term residents of Nogales and listened to the stories of deportees about their experiences of the wall and the nearby desert.

On a map, a distinct line defines the boundaries of the United States. Many Americans believe that the real border has this same clearly demarcated reality, but in fact, the border has always been a permeable frontier. Following the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, the towns of Ambos Nogales developed in a mountain pass that served as a travel route between the two countries. For most of the 20th century, the border in Ambos Nogales was demarcated by a metaphorical “picket fence”—a chain-link fence that did little to stop casual border crossings.

During the picket-fence period, both the United States and Mexico engaged in mutually beneficial international development in Ambos Nogales. Civic leaders in Ambos Nogales were businesspeople specializing in cross-border commerce, with profound binational and bicultural knowledge, orientations, and social networks. Ambos Nogales existed as a space of cultural mixing. Mexican and American citizens easily traversed the border in Nogales to visit family and friends, buy goods that were unavailable or more expensive on the other side, or eat in restaurants. Police forces and firefighters on each side assisted one another when necessary.

That all came to an end in 1994, when the U.S. built a 10-to-15-foot-high wall constructed of military surplus landing mats and topped with an angled steel anti-climb guard to divide Ambos Nogales between the U.S. and Mexico. The United States government had decided in the early 1990s that construction of walls in urban areas would be a good way to stop undocumented migrants and drug smugglers at the border. The official policy was one of deterrence: The new walls were meant to force would-be immigrants into the desert, where they would risk dehydration and death, and where they would be easier to capture.

When residents of Ambos Nogales objected to the ugly structure separating their communities, the U.S. replaced a short section of the downtown landing-mat wall with a tan-colored “decorative wall” in 1997. But no matter how it looked or what it was made of, the new wall did not diminish human movement across the border. It led, instead, to a dramatic increase in the number of people dying in the Sonoran Desert.

After the formation of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2003, militarization of the border increased exponentially. The number of Border Patrol agents in southern Arizona’s Tucson Sector (which includes Ambos Nogales) more than doubled. These agents carry automatic weapons and wear bulletproof vests, and some participate in the Border Patrol Tactical Unit, a fully militarized SWAT team. ICE manages a system of “layered security” at the wall that includes vehicle barriers, surveillance equipment (sensors, floodlights, tripwires, cameras, mobile observation towers, radar, blimps, and Predator drones), and active patrolling by agents and dogs.

Not surprisingly, along with militarization has come an increase in violent confrontations between agents and border crossers. It also has led to the ruination of the downtown economies of Ambos Nogales, as legal cross-border tourists and shoppers are discouraged by the move toward separation and militarization. In Nogales, Arizona, empty storefronts line the downtown, reflecting the 30 percent decline in business that occurred between 2002 and 2011. Of the 700 curio shops that used to operate in the tourist district of Nogales, Sonora, only 33 remained by the end of that same period, and the surviving shops reported an 80 percent decline in business.

In 2011, the U.S. further increased the militarization of the border when, at a cost of $11.8 million, it tore down the landing-mat wall and erected a new 18-to-30-foot-high, 2.8-mile-long bollard wall through Nogales. The new wall consists of concrete-filled steel tubes called bollards, placed 4 inches apart so that agents in the U.S. can see potential crossers or climbers on the Mexican side, and it is set in an 8-foot-deep concrete foundation to thwart tunnelers. From the perspective of people on both sides, the new wall makes Ambos Nogales resemble a prison.

But the militarized wall has not stopped migration. It has merely changed where and how the undocumented cross the border and has made border crossing increasingly dangerous for the poorest among us. The desperate and impoverished who have already traveled for weeks or months across Mexico braving rape, robbery, and bodily injury are not deterred by a physical barrier or displays of U.S. military muscle. Rather, they will cross or they will die. So, because of the wall, these migrants travel for miles into the desert to circumvent the barrier, walking for days across the Sonoran Desert with minimal gear and little water, subject to heat stroke, dehydration, injury, and predation by the very people they hire to guide them. Since construction of the first wall in 1994, about 300 migrant bodies per year have been recovered from the southern Arizona desert. Who knows how many more are never found.

A wall height of 30 feet has not deterred climbers, despite significant risk to life and limb. Smugglers erect ladders on the Mexican side of the wall and charge a fee to climb them, but ladder climbers have to jump down on the U.S. side; at least 200 people were injured falling from the Nogales wall in 2015. In March 2016, a Mexican TV news crew videotaped two young men scurrying over the Nogales wall in 15 seconds.

Tunnelers smuggling people and narcotics have integrated their own passageways with an existing trans-border sewage/drainage system (the two cities still share a common sewage treatment plant). People crossing through the tunnels must wade through raw sewage, beat off rats, and fend off criminals that seek to rob or rape them. When heavy rains unexpectedly flood the tunnels, migrants drown. As of 2015, border patrol agents had located 108 tunnels under the wall in Nogales—obviously, the true number remains unknown.

People also cross in vehicles as hidden cargo, despite extreme discomfort and the possibility of carbon monoxide poisoning, suffocation, and heat strokes. Ports of entry have sniffer dogs and surveillance devices to find people in concealed compartments in vehicles. We met a deported migrant who had crossed by hanging under a freight train before he was apprehended on the U.S. side and severely mauled by patrol dogs.

Many people also cross the border legally and then stay longer than the terms of their visas. Calculating exactly how many immigrants overstay their visas is difficult, as is calculating how many migrants sneak across the border. From October 2014 through September 2015, the U.S. Border Patrol intercepted 331,333 migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, while the Department of Homeland Security calculated that about 416,500 people overstayed their visas. Visa overstays may account for the majority of undocumented migrants entering the U.S. The wall, of course, does nothing to stop them from staying.

Walls are not just barriers. They are also surfaces and symbols that can be employed for subversion, and people use the wall in Nogales to protest its very existence. Protests have come in the form of art installations, graffiti, placards, and demonstrations. Chicana artist Ana Teresa Fernández, for example, tried to visually erase the bollard wall with sky-blue paint.

The border wall serves as a focal point for protest of racist policies—racist because the policies are focused on migrants from Mexico and points south, compared to migrants from other parts of the world. At the wall, people maintain day-to-day interactions that unify rather than divide their community. Families separated by the wall meet there to talk, picnic, and pass children’s schoolwork through the bars, maintaining the social bonds that the wall disrupts.

In October 2012, a hyper-militant border patrol agent on the U.S. side of the bollard wall shot and killed a Mexican teenager, José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, who was on the Mexican side. Three weeks later, on the holiday of Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), protestors on both sides of the border gathered at the spot where he was killed. José’s mother, Mexican citizen Araceli Rodríguez, reached between the bars to embrace U.S. citizen Guadalupe Guerrero through the wall. Border Patrol agents had shot and killed Guadalupe’s son Carlos while he was scaling the border wall in Douglas, Arizona, the year before. The scene was a powerful symbol of the shared humanity that prevails despite the state’s imposition of a barrier that has violently impacted so many people.

The proposed border wall is an expensive folly. President Trump wants to build a 30-plus-foot-high wall along the roughly 2,000 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border. The wall through Ambos Nogales extends for 2.8 miles and cost taxpayers US$11.8 million, or US$4.14 million per mile. It is part of an existing system of about 700 miles of such barriers. To extend the wall along the remaining 1,300 miles of the border would cost taxpayers even more per mile due to the rugged, remote desert terrain through which much of it would run, with a total cost estimated at US$12 to $40 billion.

And, as the experience in Nogales illustrates, a barricade would never effectively stop the movement of people. This violent physical incarnation of U.S. political ideology is doomed to fail. Migrants, cartels, and people living at the border have found a myriad of ways to go over, under, and through the Nogales wall. It would be even easier in the hundreds of miles of isolated desert where the new wall would be built. And it would do nothing to stem the flow of the hundreds of thousands of people who remain in the U.S. illegally on expired visas. Migrants desperate to enter the U.S. will never be deterred by a wall. They will risk injury and death trying to circumvent it, and in the process, they’ll venture ever farther into the killing ground of the Sonoran Desert. President Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” would be nothing more than a tremendously expensive way to increase human suffering.