How Babywearing Went Mainstream

Danielle Gold has 18 baby carriers but only one baby. She estimates that her collection of wraps, mostly made up of long pieces of woven fabric used to secure the baby to her body, is worth at least US$2,500. And she says each one looks and feels unique and can be tied in different ways, depending on its material and size. For the last few months, she has rarely used most of these wraps, preferring the few structured carriers she owns as her daughter gets bigger and heavier.

But when her now 22-month-old daughter was younger, Gold liked to scroll through the Facebook posts of babywearing groups, including one called the Babywearing Swap, which has more than 118,000 members. Though based in Jerusalem, Israel, Gold is part of a flourishing online global community—and marketplace—that’s grown up around the revival of babywearing, the practice of using a carrier to buckle, wrap, tie, or otherwise strap a child to a caregiver. Babywearing keeps the baby in close contact yet leaves the hands of the caregiver free for other tasks. Last year, Gold commissioned someone she met online to hand-weave a custom baby wrap for her to the tune of US$550. In January, she paid US$200 for a secondhand, limited-edition wrap.

These relatively ordinary objects have re-emerged—largely through the help of the internet—as items of value, expressions of identity, and a way for parents to connect with one another. A strong emotional current, therefore, underlies the collecting of wraps—and bolsters a flourishing secondary market, says Natalie Djohari, a visiting research fellow in anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London, who has studied the secondhand baby carrier market. Djohari owns six wraps, which she used with her children. “People are not passive consumers about these things,” Djohari says. “Buying a wrap becomes a search for something that is extremely meaningful, with people putting in a lot of effort. It is really a labor of love.”

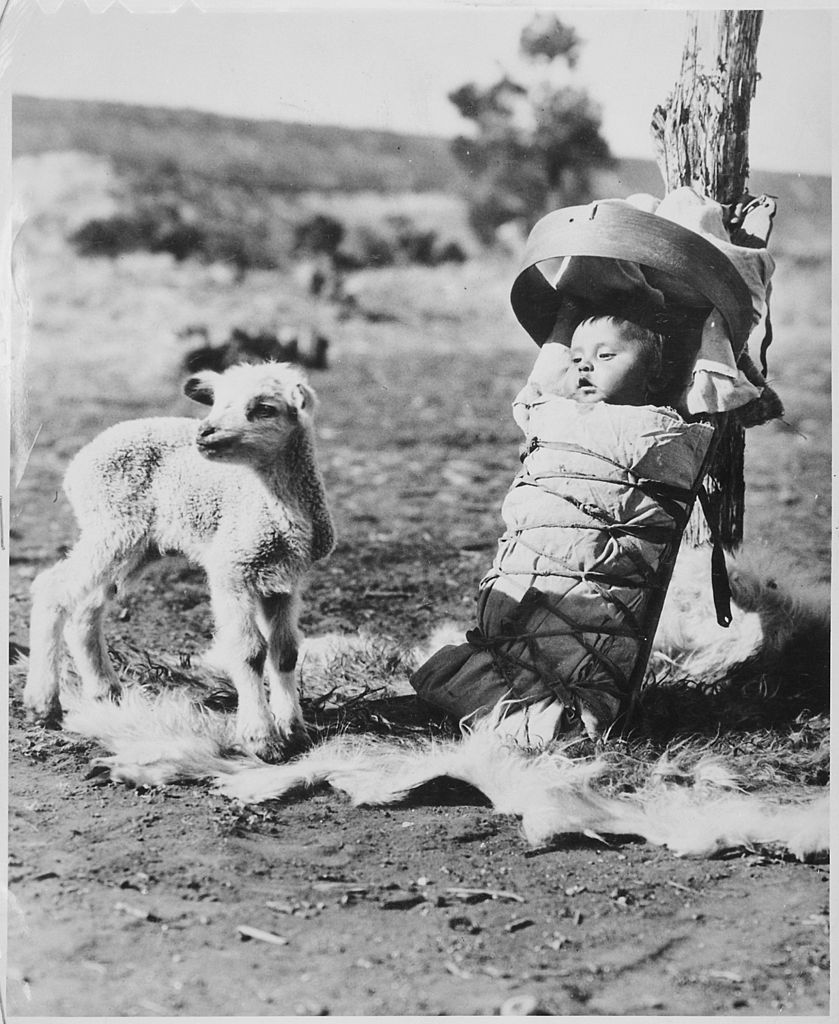

From an evolutionary perspective, humans are a “carrying” species—meaning we have always kept our babies close, taking them along to forage for food—as opposed to a “parking” species, such as wolves, that hides its young in dens or elsewhere while going out to search for food. The musculature of many primate newborns is strong enough to allow the infant to cling to its mother. But as humans evolved, a growing fetal brain size led to bigger heads that took up more room in the womb. Such changes caused fetuses to be born earlier, so human infants are not yet developed enough to cling to their mothers. As a result, early humans, at least half a million years ago and probably earlier, began making carriers. These may have been constructed from animal skins, plants, and leather cords to strap babies to the chests of their caregivers—making such carrying devices among the first tools developed, says James McKenna, an anthropology professor at the University of Notre Dame who studies mother-infant relationships.

Carriers became the norm for transporting babies, although the materials and designs varied greatly in different times and places. Art from Pharaonic Egypt depicts women with baby carriers, and a 14th-century fresco in a church in Padua, Italy, portrays Mary carrying the baby Jesus in a sling while astride a donkey. But the use of carriers in Western societies fell out of style beginning in Victorian-era Europe when baby carriages became fashionable. As attitudes toward child rearing shifted and parents began to worry about spoiling their children—viewing them more and more as independent beings—mothers chose carriages to create space between themselves and their babies. With the rise of carriages and new parenting attitudes, carriers came to be associated with lower classes and with non-Western cultures.

Only in the 1970s did carriers begin to make a gradual comeback in the United States when a nurse named Ann Moore debuted the Snugli, a soft-structured carrier with shoulder straps that can be worn in front or back. The concept was inspired by Moore’s work with West Africans while serving in the Peace Corps in Togo. A few other companies that offered wraps and slings also sprang up around the same time. Like Moore, most of the entrepreneurs behind these products had learned about babywearing in the developing world, where it never went out of style.

Babywearing slowly gained acceptance as approaches to parenting changed in the United States throughout the 1990s—most notably with a marked increase in rates of breastfeeding and a shift away from the idea that babies needed to be taught to self-soothe, McKenna says.

“Through the years, babywearing became less taboo,” says Tina Hoffman, managing director at Didymos, a German company that has been making woven wraps since 1972 when Hoffman’s mother needed something to carry her and her twin sister. The practice attracted a lot of stares and attention in their German village, but, Hoffman explains, her mother believed so strongly in the benefits of babywearing that she raised funds and started making and selling wraps.

Over the last decade, the practice of babywearing has surged, having moved out of the ideological niche of attachment, or natural, parenting that it previously occupied. Many credit the internet, and especially social media, for its spread. “Social media helped give babywearing a more mainstream face,” says Alisa Heytow DeMarco, founder and owner of Tekhni Woven Sling Studio, which she started in 2013.

Now, instead of only being exposed to the practice through a chance encounter with a local babywearing group or a store that sells carriers, new parents often learn about it through their Facebook feeds—either from posts or targeted ads; they can instantly research and buy carriers online. Such exposure also likely informs them about the health benefits of babywearing.

Medical studies have shown that babies who are carried cry less and are more content than those who are held less frequently. Carrying has also been linked to improvements in the development of premature infants. And though there is little scientific research to back up this claim, a lot of anecdotal evidence shows that babywearing promotes bonding, which is believed to ease postpartum depression in some mothers.

The industry’s growth has also been supported by an increasing number of certified babywearing consultants—people who are trained to teach others about the safe and comfortable use of baby carriers—as well as organizations like Babywearing International that seek to educate parents and other caregivers about how to use wraps and slings. In addition, retailers have catered to the popularity of babywearing: Target stores alone now carry 19 brands of baby carriers, with many of those brands offering multiple styles.

Social media not only creates an easily accessible and visual marketplace—it also provides a setting that conveys how much value people place on these items, explains Djohari. In her research into online babywearing groups, Djohari found that many women sought out certain colors and patterns in order to express their maternal role, personal identity, or family history. And because of a wrap’s incredibly important use, the process of choosing one can be more emotionally loaded than picking out other accessories. “It’s different than shoes,” she says.

This emotional aspect is what leads people to buy multiple wraps, as they seek to express different facets of their identity, Djohari says. The heightened sense of meaning found in the object also leads people to pay high prices on the secondary market for wraps that were limited editions or have been discontinued, she observes. “It’s very easy to become obsessed with a certain carrier.” Secondhand wrap transactions are often emotional too, Djohari notes, with buyers and sellers connecting through photos and online messages. And, even though money is changing hands, the sale and transfer of a wrap is sometimes treated as giving a gift, with sellers doing things like including a card or additional items like chocolates.

“There is an underlying current that this should be about more than money, so we see these tropes of gifting,” Djohari says. “These are items related to babyhood, so it shouldn’t be just about cold, hard cash.” But parting with carriers can also be emotionally difficult, she says. The carriers are “invested with such intimate memories,” says Djohari, who still holds onto her wraps even though her children are too big for them, that in reselling them, “you are also relinquishing that time.”

However, the gift-giving aspect and the idea that future owners will understand the emotional value of the item can help make it easier for people to part with wraps they have used with their own babies, Djohari says. For example, in packaging a carrier nicely, the seller can concentrate on feelings of generosity rather than loss.

According to Beloved Burden, a book about babywearing around the world edited by Dutch anthropologist Itie van Hout, baby carriers have always held “exceptional significance for their users.” In some cultures, carriers are treated as sacred objects. One common denominator among the vast variety of carriers from different cultures, even from ancient times and in relatively poor communities today, is that they are decorated, often with amulets for protection or with symbols of fertility, van Hout writes. In the Hmong community in northern Thailand, babies are worn in carriers made by their grandmothers. “The sling is therefore a symbolic expression of the succession of generations,” van Hout writes.

In the West today, rather than reflecting traditions of preceding generations, babywearing is a culturally borrowed practice with a large learning curve due to the proliferation of so many different types of carriers in recent years. However, the existence of this learning curve and the desire for a more connected style of parenting is what has propelled modern babywearing—and other revived practices such as using cloth diapers or breastfeeding—to become the basis of a community and a source of cultural identity.

The realm of babywearing, with all its online groups, in-person meetups, international conferences, and product lines, demonstrates how new parenting cultures form in a world connected by technology. It has become common practice to deeply research various baby products and care methods, writes Nancy Ukai Russell in her 2015 article “Babywearing in the Age of the Internet,” published in the Journal of Family Issues. For many, such research and education leads to “the formation of social communities in which mothers display creativity, dedication, and competence as they develop and express their maternal identity through babywearing,” Russell writes.

These communities fill a deep need for parents today who are often making choices based on research rather than simply following a tradition. Mainly, says Russell, who studied a babywearing educational group in California, they help relieve parental anxiety and offer validation for parenting choices.

“Part of what makes it so compelling, so fun, is about the community,” says Emily Lightstone, who moderates the Babywearing Israel Facebook group. She recalls that someone who lives on the other side of the world gifted her a wrap worth US$200 after learning that her father had passed away. It’s experiences like this, she says, that keep her involved in several online babywearing groups, reading and discussing different types of carriers and how to use them, even though she already owns 12 carriers for her two sons. “It’s really become a lifestyle.”