How People Actually Use Their Smartphones

In 2022, the smartphone, first introduced by IBM, will celebrate its 30th birthday. Most of us now use a smartphone every day—whether we like it or not. Previously associated with young people, these technologies have become ubiquitous around the world and among all age groups. But what exactly is a smartphone, and what are these devices doing to people’s connections with one another, especially across generations?

That is precisely what our long-term collaborative study, the Anthropology of Smartphones and Smart Ageing, set out to investigate. A team of 11 anthropologists conducted 16-month-long ethnographic studies across nine countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. Our researchers then compared their findings on the impacts of the device on the experience of midlife and aging, paying special attention to the field of mobile health technologies.

One major finding with implications for public health is that people are adapting popular messaging apps such as WhatsApp to support their health, rather than relying only on formal mobile health apps and other top-down public health initiatives. As COVID-19 took hold in 2020, looking at how people were using smartphones became even more urgent. Smartphones became seen as devices that can receive and deliver care—but they also are used for what could be perceived as surveillance, whether by relatives, friends, authorities, or the state.

At the same time, for many during the pandemic, smartphones became the main instruments facilitating social connection and communication with family and friends. Our project aimed to capture the positives, the negatives, and the complexities in between when it comes to how people around the world relate to these devices.

Along with publishing our findings in book format, our project is committed to pushing the boundaries of academic dissemination through research-driven visual storytelling. Three comics that illustrate our findings are presented below. These were created through a collaboration with U.K.-based comics artist John Cei Douglas.

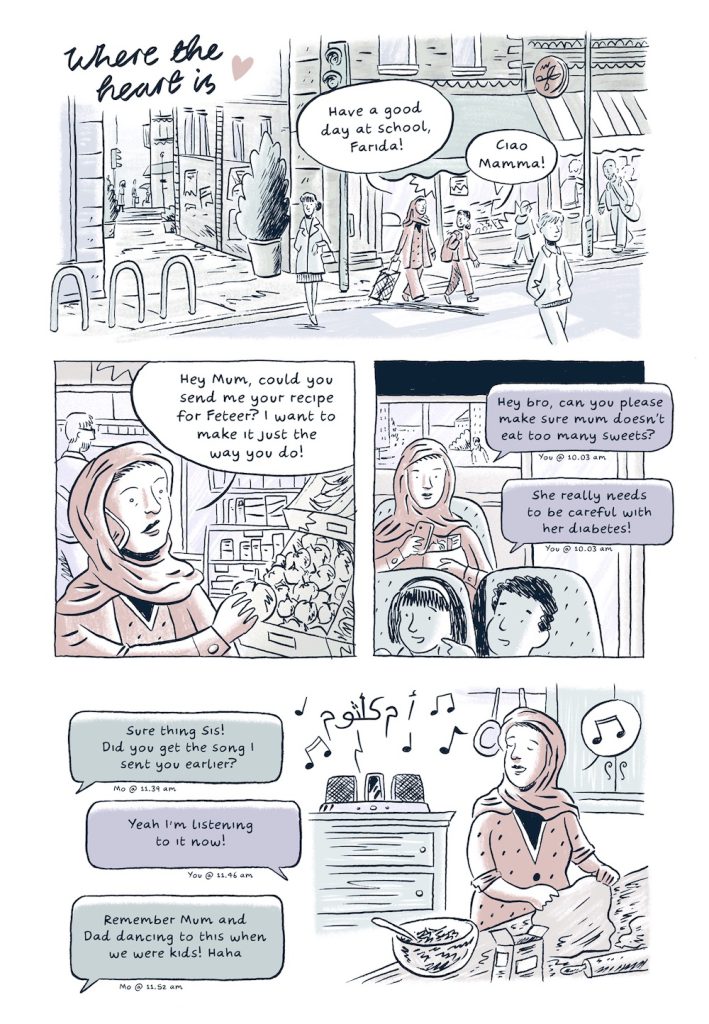

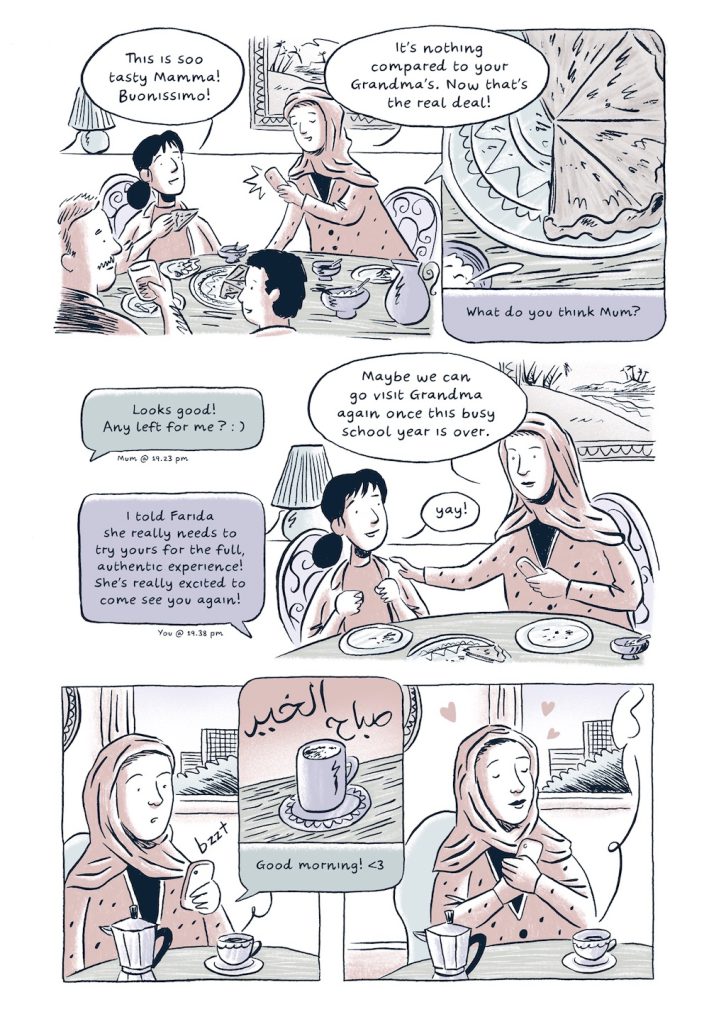

“Where the Heart Is” (Milan, Italy)

Comic based on Shireen Walton’s research in Milan, Italy. Scripted by Laura Haapio-Kirk and Georgiana Murariu, and illustrated by John Cei Douglas.

The smartphone, several of our researchers found, has become a place within which we live—what we call a “transportal home.” Our researcher Shireen Walton found that migrants from Egypt, Peru, and other countries who were living in Milan, Italy, were especially connected to their smartphones for this reason. Smartphones allowed migrants to be together simultaneously with loved ones in their home countries and where they live now, making it possible for them to locate “home” in interwoven digital and physical domains.

In the comic below, meet Heba, an Egyptian migrant in her mid-40s living in Milan. [1] [1] All names featured in the comics have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Heba maintains attachments to multiple homes within the space of her smartphone.

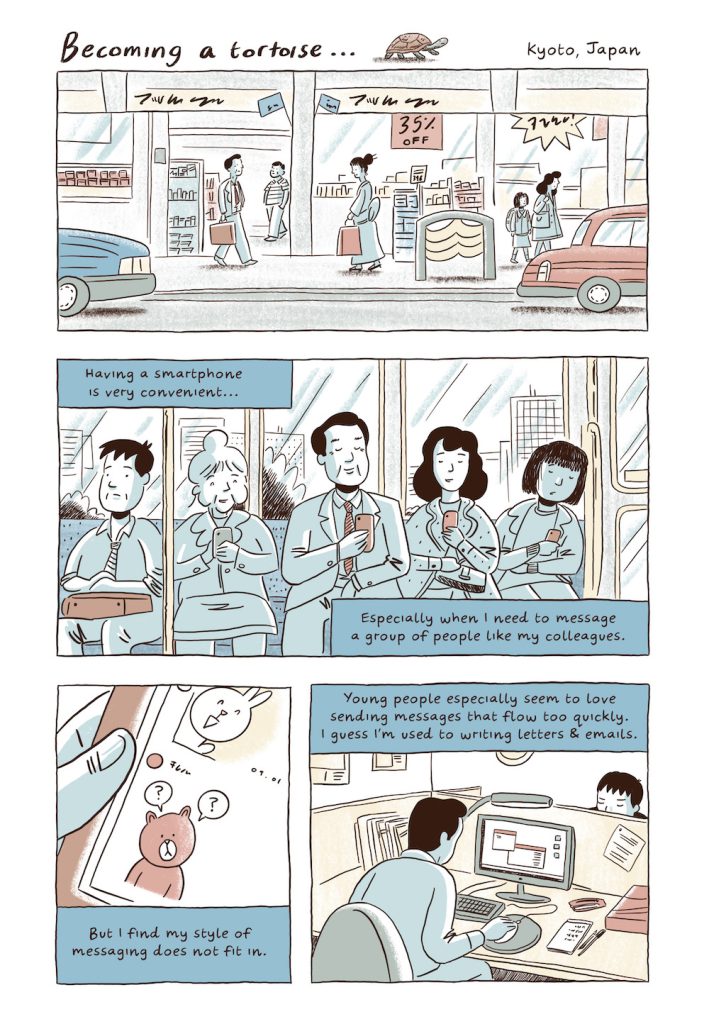

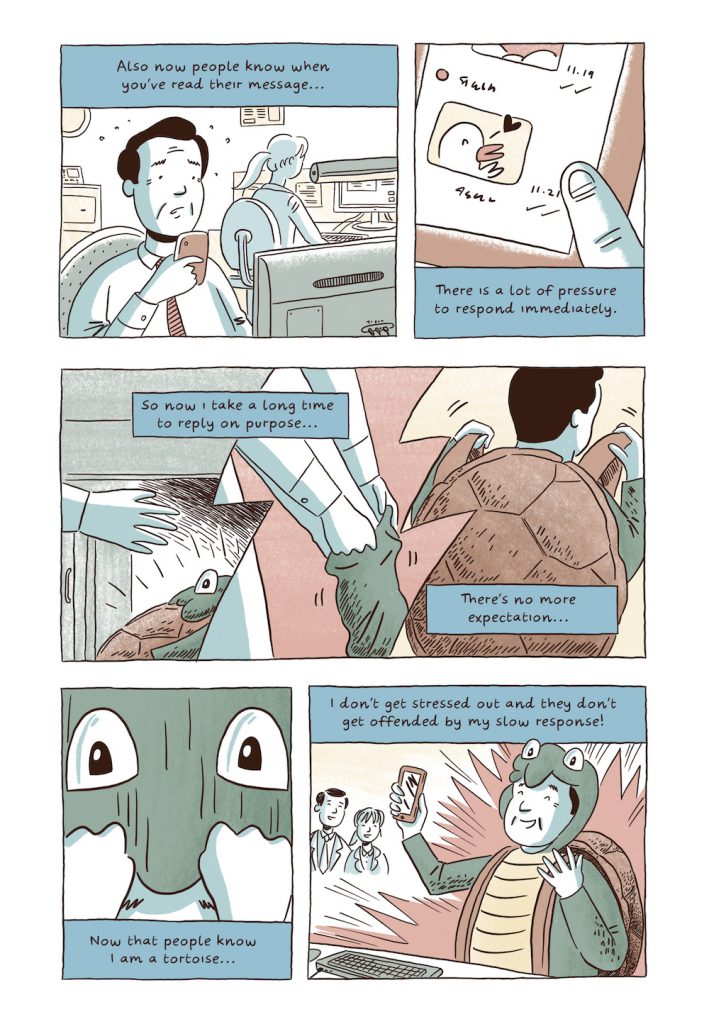

“Becoming a Tortoise …” (Kyoto, Japan)

Comic based on Laura Haapio-Kirk’s research in Japan. Scripted by Laura Haapio-Kirk and Georgiana Murariu, and illustrated by John Cei Douglas.

Prior to the rise of smartphones, people mainly communicated using their voices and through writing. Now, non-textual visual forms—such as videos, stickers, and emojis—have become an integral element of conversation for many people. I (co-author Laura) found this particularly true in Japan, where people rely heavily on stickers and emojis on the popular messaging platform LINE (the Japanese equivalent of WhatsApp).

The smartphone has extended the capacity for human communication for many, including older adults who find communicating with stickers more convenient than typing out long messages and worrying about typos. At the same time, this fast-flowing form of conversation can alienate others who are more used to longer and slower forms of communication. For instance, “read” receipts often translate to a social obligation to respond quickly—particularly in Japan, where people are often acutely aware of maintaining harmonious relationships with others.

In the comic below, Hiro-san, a man in his early 50s, finds his smartphone convenient, but he worries that his style of messaging marks him out as different from others. He thus develops his own way of dealing with this pressure, embracing his tendency toward slow, deliberate textual responses, similar to the emails he is used to sending in the workplace.

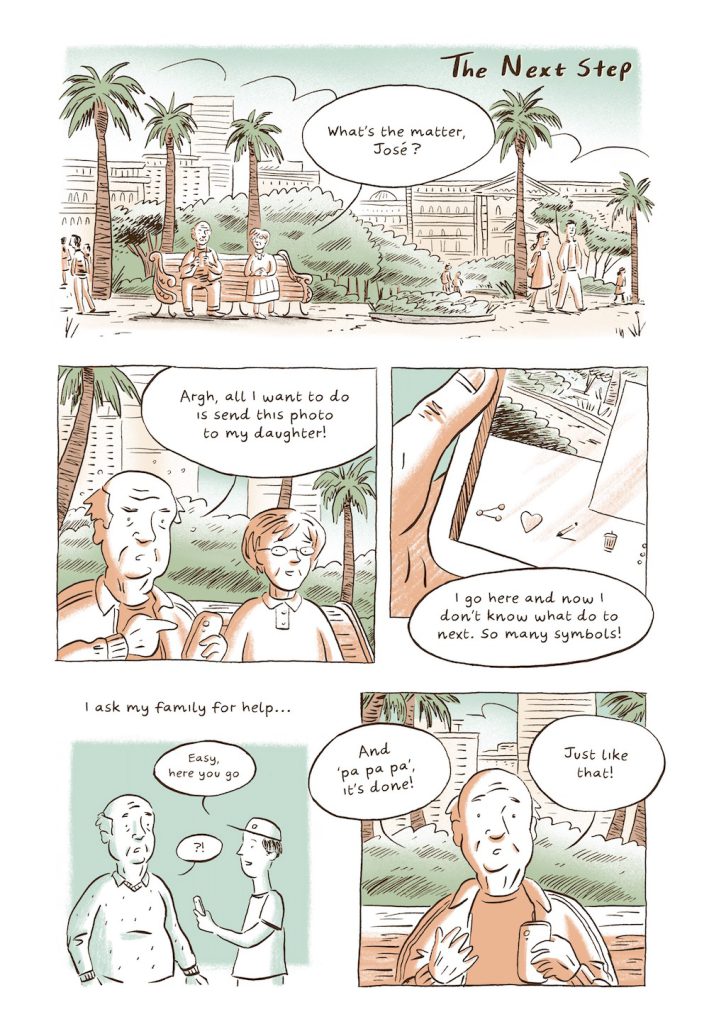

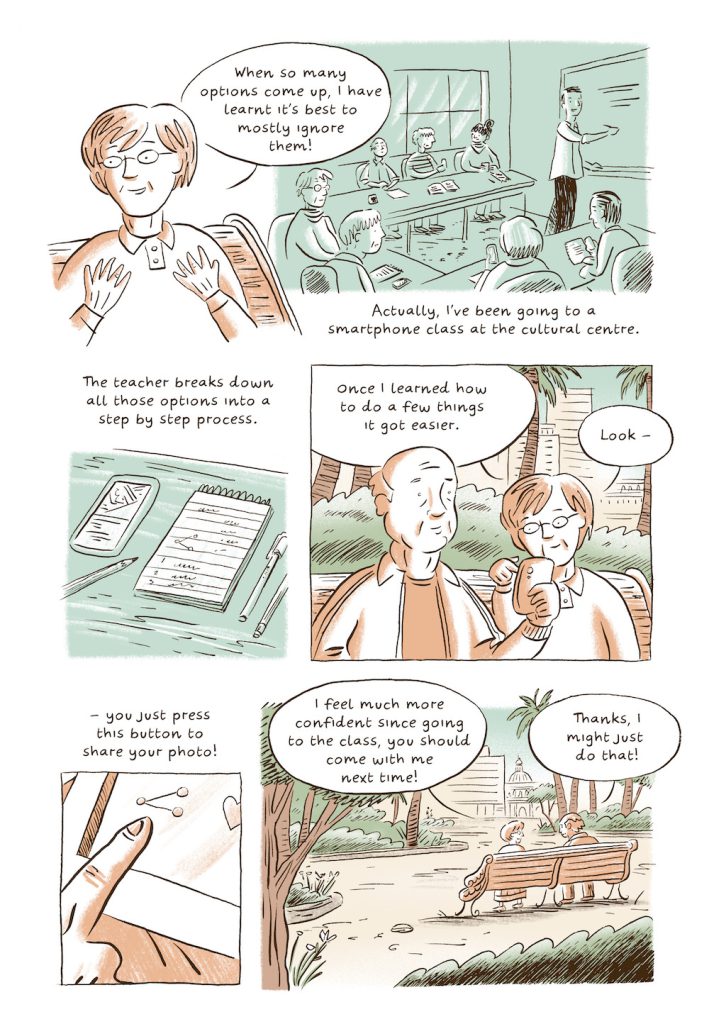

“The Next Step” (Santiago, Chile)

Comic based on Alfonso Otaegui’s research in Santiago, Chile. Scripted by Laura Haapio-Kirk and Georgiana Murariu, and illustrated by John Cei Douglas.

In some field sites, the challenges of learning how to use smartphones has impacted intergenerational dynamics. In Chile, our researcher Alfonso Otaegui volunteered at a center teaching older adults how to use smartphones. He found that elders—historically, the keepers of knowledge and wisdom—were finding themselves becoming dependent on younger people, who do not always have the patience to teach them how to use new devices.

These pressures are exacerbated by the fact that the Chilean government is increasingly pushing the digitalization of all services and aims to go “paperless” in the near future—a process that has made older adults anxious that they might be left with no choice but to use a smartphone to access specific services, even if they do not feel confident doing so. Otaegui found that once older people mastered smartphones, however, all sorts of new possibilities opened up for them.

In the comic below, a man in his late 60s named José struggles to use his smartphone to communicate with his daughter—until he meets a friend around his own age to help him.

Next Steps

We are currently in the process of creating more comics to share our findings. For example, an upcoming comic based on Marília Duque’s research in Brazil illustrates how smartphones are shifting how many people operate as families. By allowing people to reincorporate extended family members into their lives, smartphones enable more of us to participate and live in larger family groups, even if we’re located far apart.

Read more about the process of making these comics on our blog. Once we have completed the full set from each field site, the comics will be available as a downloadable zine on our website. In the meantime, find other free resources related to our project on YouTube and FutureLearn.