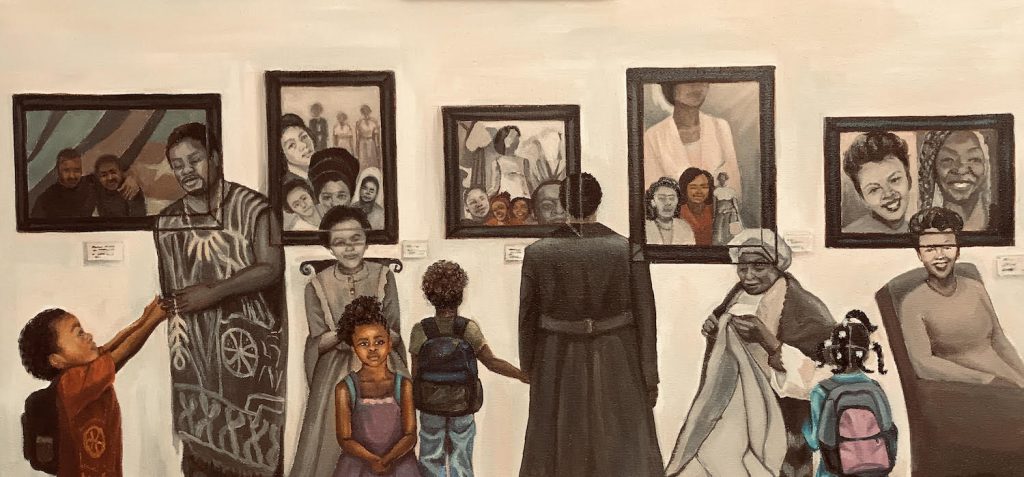

Lead Me to Life: Voices of the African Diaspora

In 2020, George Floyd’s murder by Derek Chauvin, a White police officer in Minneapolis, flared a global nerve. Black Lives Matter protestors stood up against anti-Black racism and police violence—bringing to the fore how colonial and imperial systems have not died but morphed into new forms of state surveillance, suppression, and violence against Black and Brown people around the globe.

In response, we—a team of editors, poets, and anthropologists based in the U.S.—put out a call for anthropologists of the African diaspora to share their creative work with us. We asked them to offer their voices and perspectives on this moment and on the 500-year history of African diaspora and culture that began with the transatlantic trade of enslaved Africans. They met this call by bringing a wholeness to their storytelling, working to dismantle dominant narratives and ways of knowing, refusing the “White gaze,” and claiming personal experiences as powerful ethnographic material that can shape hearts and minds and futures.

The resulting collection, Lead Me to Life: Voices of the African Diaspora, uses creative scholarship to bring nearer a shared future of safety, vitality, equality, and justice for all those of the African diaspora. Through explorations of family and ancestry, the personal/autobiographical, how the past echoes into today, and the human hurts of social inequality, the collection contributes to a 2021 global reckoning with anti-Black racism, anti-queer violence, sexism, anti-Asian hate, European colonialism and slavery’s afterlives, and much more.

As academics, we know that scholarship alone will not bring about the change many of us seek. Poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction, among other genres, are essential to how we embody and experience our always shifting worlds. Throughout the African diaspora, creative works carry the weight of social change.

In putting together this collection, we were inspired by influential works such as literary scholar and cultural historian Saidiya Hartman’s essay “Venus in Two Acts,” which wrestles with the elision of Black girls from the public memory of racial violence. Through an encounter with archival documents about an enslaved “dead girl” named Venus who died on board a British slave ship named Recovery as recorded in 1792, Hartman delves into the traffic between fantasy, fact, violence, and desire in an interrogation of the “archive” (the documents, statements, and institutions that decide our knowledge of the past) of Black life.

Poetry pushes us to reckon with the deeper truths of social repair.

Using “critical fabulation,” the splicing and reconfiguring of the scant information in the archives, Hartman troubles assumed narratives and rewrites against collective amnesia. Her work shows us what it means to be Black in the world—specifically, to be Black and female in the Americas and trying to survive in the afterlives of the Middle Passage, slavery, and its residual terrors. Hartman shows what it is to split one’s Black self in two as a means of navigating the tenuous mortality of Black intimacy, Black community, and Black life.

We also turned to poetry—as people often do in times of personal and social crisis. Popular works of poetry, such as Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, are already essential reading for this current moment of racial reckoning in the United States. Citizen’s powerful lyric arcs between words and media, pushing the boundaries of the lyric poetry form to reveal the distortions of racism and warping of social ties. Poetry is open-ended. This openness allows a poet to grapple with unthinkable or barely thinkable violences that are hidden in everyday life—and, as readers and listeners, poetry pushes us to reckon with the deeper truths of social repair.

But more than asking contributors to respond to ongoing acts of racism and violence, and the uprisings, we sought work that spoke to African diaspora survivance (active, ongoing presence), Black joy, freedom dreams, collective healing, and other empowered practices.

The voices in this collection rise from many sites around the globe.

The African diaspora includes worldwide communities of native Africans and people of African descent who move or are the descendants of those who moved through global systems of enslavement, colonialism, nation-building, and immigration. In the Americas, the diaspora community focuses mainly on descendants of the transatlantic slave trade of the 16th through the 19th centuries. The United States may have banned the slave trade in 1808, and legally abolished slavery in 1865, but the country did not dismantle many systems of oppression linked to the slave system. The works grapple with these ongoing histories.

Dina Rivera’s poem “Middle Ground” speaks directly to the “dear ones” who have lived, and are living, in this diaspora. As an Afro-Taino archaeologist based in Florida, she navigates a system intent on dehumanizing and disenfranchising Black and Indigenous people, among others, which, as she says, “is an exhausting dance between survival and a preventable death.” Rivera’s letter-poem reaches out to herself and others of the diaspora: “Dear one, / Grant your pounding heart a moment / Your steps may falter in a world that blames you.” Her timely poem “Riot” zeros in on protestors who bleed “the dark secrets / Reflected in riot shields and badges.”

In “The Voice of Diaspora,” Black Brazilian poet and archaeologist Lara de Paula Passos speaks in the imagined voice of diaspora, offering a poetic definition that is rooted in her personal experience and family history: “I am Diaspora / and also Colony / Made of Love and Ammonia.” Embracing the contradictions of a community built on a shared violent history, Passos’ poem gestures toward forms of belonging beyond national borders and legal citizenship. In its strongest expression, diaspora models more inclusive ways of sharing identity that trouble simplistic racial or nationalistic categories.

Poet and author Jason Vasser-Elong, of Cameroonian descent, offers a trio of poems—“Elder,” “Window,” and “Lessons We Learn”—that are intimate portraits of family heritage in the United States. Ethnographic richness animates his recollections of road trips through woods tinged with memory: “There may even come a time / when a forest will only be trees. / But for now, it’s the setting for a memory / not mine, but ours.” We come away from his poems imagining a world that might be all ours but seen from unfamiliar angles and perspectives: “nights so black, so lit with stars / that one could imagine that it’s dark everywhere.”

Anthropologist Cory-Alice André-Johnson, who works in and writes about Madagascar, offers the only work of fiction in the collection. In her story, “They’ll Steal Your Eyes, They’ll Steal Your Teeth,” local children are disappearing—or being stolen. She uses gossip about the missing children to investigate how different kinds of talk embody or refuse the demands of those in power. Her story reveals the inequalities at the heart of postcolonial contexts such as Madagascar, where race, capitalism, imperialism, and class, among other forces, shape speech, communities, and rights. Gossip about vazaha (a Malagasy term for foreigners, who are largely Europeans or of European descent) hides and unveils what people know or don’t know in a cadence of uncertainty: “Nobody knows. Ask anyone. Everybody knows. … They take people. They take land. They take bones. Vazaha take vacations. They take pictures.” Andre-Johnson’s piece highlights how ethnographic fiction can expertly and powerfully combine rigorous field research with creative writing methods.

Black surfer and anthropologist Traben Pleasant draws us into the waters of Bocas del Toro, Panama, to witness “African diaspora riding waves across the surfable globe.” Hailing from Long Beach, California, Pleasant typically found himself the only Black surfer in sight. While doing ethnographic work in Panama, one day he became immersed in a scene that brought elation and questions: “a palette of Black canvas-riders”—none of whom aligned with the “White sport” narrative that says, “Blacks can’t swim.” His poem “Surfing in Color” broadens the lens through time and space of the range of Black surfers who have thrilled in riding waves.

Centering us back in the U.S. but with a broad lens, poet and anthropologist Irma McClaurin’s contribution “Are We So Different?” was first commissioned for the American Anthropological Association’s project on race in the United States called RACE: Are We So Different? Crafted to respond to white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, her piece reminds us: “We can choose to enmesh ourselves / in prejudices and racism, / or choose to be humane.”

Carving spaces of influence outside and inside of academia, our contributors help us feel the significance of the past and call us toward humane, just, and joyful futures. To do this celebratory and healing work often requires writers to immerse themselves in troubling waters—a task augmented by the trial of experiencing the various inequalities, deaths, and oppressions committed in real time upon those who make up the African diaspora.

We as editors highlight and take account of the enduring courage and craft it takes to creatively transmit one’s lived reality of Black joys, pains, loves, and losses to the world.

Editors’ note: Carla Keaton painted the header image based on photos submitted by some of the contributing authors to this collection.