Do Black Lives Matter in Outer Space?

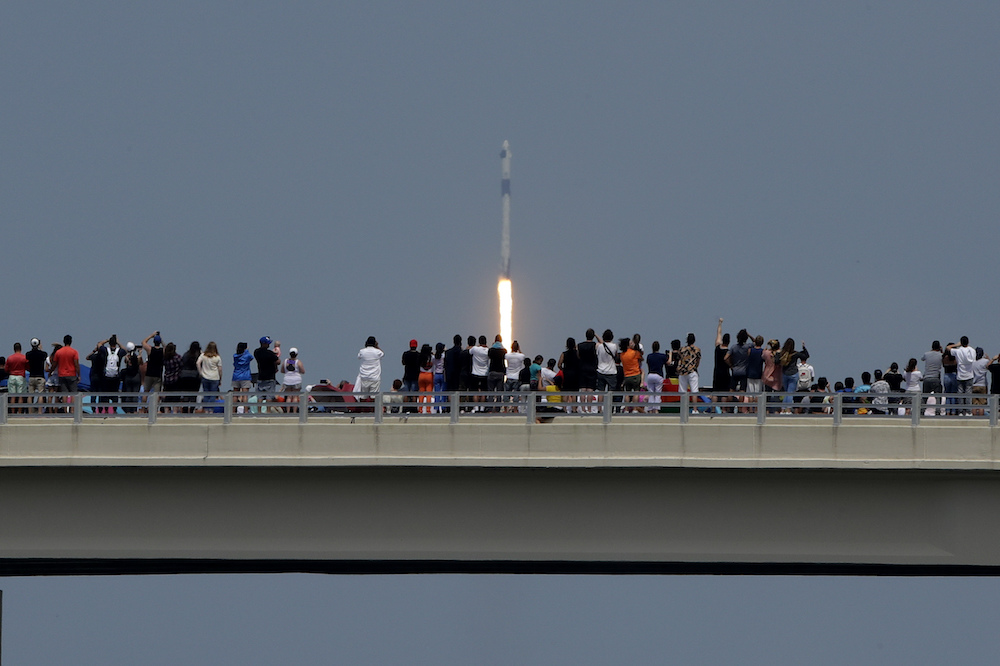

On May 30, I tuned in to see the launch of the SpaceX Crew Dragon from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The Dragon, the first spacecraft to launch from U.S. soil in nearly a decade, was to herald the dawn of a new age of space colonization.

As I watched the astronauts on TV clad in futuristic designer-made suits prepare for blastoff, my mind was flooded with memories of my childhood in Jamaica. As a young girl in the 1990s, I spent hours poring over my Childcraft encyclopedias. I particularly loved the thick, brightly colored volume titled Our Universe, where I could bury my head in the stars and nurture my obsession with planets and black holes.

Moments after the SpaceX launch, the broadcasted words of President Donald Trump jolted me out of my reverie. He was giving a speech to the crowd gathered for the launch. “The United States has regained our place of prestige as the world leader,” he announced.

The president’s usual bluster-filled language about American greatness rang particularly hollow that day at Cape Canaveral. At that exact moment, hundreds of thousands of Americans were protesting in response to the horrific killing of George Floyd, an African American man who was in police custody, only five days prior. Floyd’s death had embodied, in 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the ugliest of America’s fractures.

Even as a girl, it had never been possible for me to escape for too long into dreams of being an astronaut. I was always acutely aware, in my own child-like way, of my precariousness here on Earth. While growing up, I faced a lost family business, a lost family home, and a lost father who was desperately seeking work in the United States. My intimate losses were statistical casualties in Jamaica, a country struggling with economic insecurity, crime, migration, and the terms of what it meant to truly be “postcolonial” on an increasingly globalized planet.

The wonders of the universe, I learned, could not shield me from the fractures in the world around me.

And so, on that perfectly clear May afternoon, I was struck by this juxtaposition of images that felt strangely familiar: At Cape Canaveral, Americans were being ushered to look to the stars to imagine the utopic future of humankind in space, while in the streets, they were confronting the country’s dystopic underbelly of anti-Black racism.

I have yet to realize my childhood dream of traveling to space. However, I did discover the anthropological galaxy after leaving Jamaica for the U.S. as a teenager to seek a new intellectual frontier.

Today, as a Black anthropologist living and working in New York City, my position in the world has changed. But my scholarly work still ties me to Jamaica, where I came of age. My research focuses on how concerns about crime and security in Kingston, Jamaica, have come to organize social life in this Caribbean capital city. From this personal and intellectual vantage point, the two historic events of May 30—the euphoric SpaceX mission and the outrage-filled protests against anti-Black racism—do not appear at odds. Rather, they are undeniably tethered.

How should Americans understand SpaceX’s goal of space colonization in a world now indelibly changed by the killing of Floyd? And will the future era of space colonization be one that is just and whole for all?

Founded by the billionaire technology entrepreneur Elon Musk in 2002, SpaceX is at the forefront of efforts to colonize space. Musk insists that one way to ensure the survival of human civilization is to make humans a multi-planet species. To make this goal a reality, Musk is committed to establishing a human colony on Mars, which will necessitate altering the red planet’s environment so it can support terrestrial life.

The fear that drives these efforts is that a natural or human-made planetary-scale crisis—such as climate change or resource depletion—will render Earth inhospitable for human beings. Put simply, SpaceX’s vision is one predicated on addressing future insecurity on Earth by creating and curating security for humans on Mars.

Space exploration is not and has never been politically neutral.

The year 2020 has tragically shown, however, that for African Americans, among others around the globe, the insecurity and inhospitableness of life on Earth is not imagined as a future eventuality. Rather, it is already being lived as a present-day reality.

Furthermore, the recent spread of Black Lives Matter protests to major international cities has reminded people that the tentacles of anti-Black racism do not simply limit their reach to the United States. Black Lives Matter is not just an American cry. It is a global movement that speaks to a planetary crisis rooted in the historic negation of the humanity of all Black people.

Though SpaceX is a private company with its sights fixated on colonizing an ecology beyond the bounds of Earth’s atmosphere, it is nonetheless implicated in these contestations about racism. Space exploration is not and has never been politically neutral.

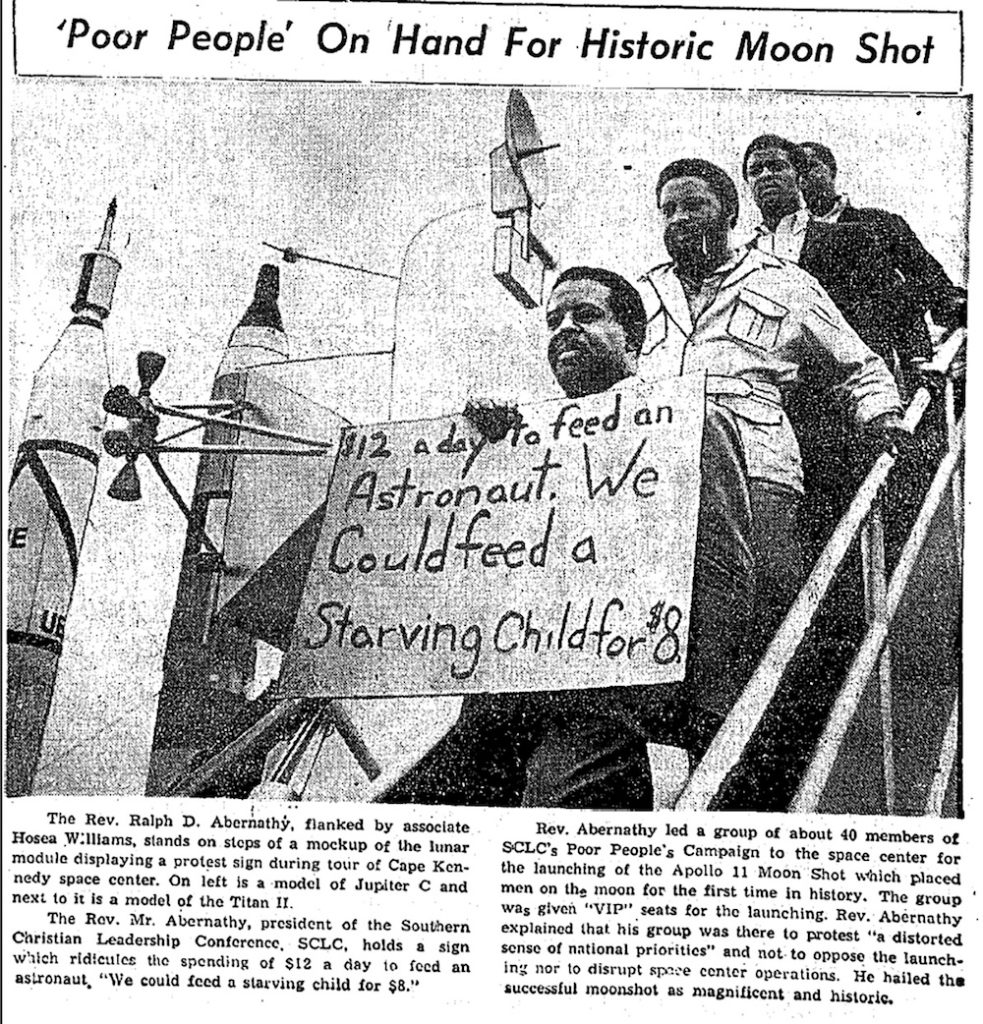

As the history of the space race shows, the dream of colonizing space has always been tied to narratives about domination and greatness. In the U.S., the historic NASA workforce has largely been White and male. As writer Mark Dery noted in a groundbreaking essay about Afrofuturism, such men seem to believe they possess the power to design, own, and control “the unreal estate of the future.”

These narratives are not unlike the ones of Euro-American colonization and imperialism on Earth, which are stories of the exploitation, exclusion, and dehumanization of Black people, other people of color, and Indigenous people in the name of exploration, adventure, and expansion by White people.

Today the scions of space colonization are the billionaire entrepreneurs who have founded commercial spaceflight companies—Musk (SpaceX), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), and Sir Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic). In other words, they are no longer political leaders from ideologically opposed nation-states, as they were during the Cold War. They are still, however, privileged and wealthy White men. (The combined net worth of Musk, Bezos, and Branson is over US$273 billion.)

Their endeavors to colonize Mars and their fantasies for the future of humankind must be understood in the context of the racialized histories of colonization on Earth.

For African Americans, race and racism have always been specters that hover over American space exploration. The late poet, musician, and author Gil Scott-Heron captured this sentiment well in his 1970 spoken word poem “Whitey on the Moon,” which was a critique of NASA’s Apollo program. Released on his debut album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox a year after U.S. astronauts landed on the moon, the poem begins:

A rat done bit my sister Nell.

(with Whitey on the moon)

Her face and arms began to swell.

(and Whitey’s on the moon)

I can’t pay no doctor bills.

(but Whitey’s on the moon)

Ten years from now I’ll be paying still.

(while Whitey’s on the moon)

As the poem conveys, for many African Americans, the Apollo program did not conjure fantastical images of human technological advancement. The first moon landing could not obscure the painful realities of social suffering that for centuries had gnawed viciously on the African American body and psyche, and resulted in the fever-like conditions of the 1960s civil rights era.

By dislodging U.S. space exploration from the realm of fantasy, Scott-Heron reminds his audience that, to the contrary, the social priorities that fueled the Apollo program and American space conquest—as envisaged by “Whitey”—were deeply implicated in Black socioeconomic dispossession and racial inequality.

Moments after the SpaceX astronauts left the Earth behind, Trump’s words rang out: “Space travel is not a feat of engineering alone. It’s also a moral endeavor—a measure of a nation’s vision, its willpower, its place in the world.”

In a post-Floyd world, the U.S. will undoubtedly have to forcefully confront the ways in which she has failed to measure up to her highest moral ideals. And yet this moment also presents the opportunity to reevaluate our collective principles to articulate once again our vision for the future, both here on Earth and in outer space.

Will this be a future equitable for all? Will it be one predicated not on Black alienation but on Black reclamation, one invested not in the fragmentation of Black people and their histories but in the project of making them whole? Will those in the U.S. be bold enough to envision such an Afro-future?

It is such a future—brilliantly depicted and embraced by numerous generations of African American literary, musical, and visual artists—that fills me with a child-like sense of wonder, much like how I felt when I first discovered Our Universe. It is in this future, that I, a Black woman, would like to make my home.